II. Discussion

Task 1. Discuss the following questions with your partner.

1. There are four ways in which all definitions of communication differ. What are they?

2. Look at the definitions of communication presented in Table 1. Which of them is the broadest and which one is the narrowest?

3. When is a broad definition good? When would we prefer a narrow one?

4. In which of the given definitions is communication viewed as a purely intentional process? Which definitions include both intentional and unintentional behaviours?

5. Find sender- and receiver-oriented definitions.

6. Which definitions restrict communication to symbolic codes?

7. Why is it useful to think of communication as a “family of interrelated concepts”?

Task 2. Define communication in the following situations using your list of definitions.

1. Two friends talking to each other.

2.The owner of the car talking to it, asking the engine to start.

3.John approaches Jane and seeing her red eyes assumes that she’s just been crying.

4.A female animal attracting a male animal by the behavior that is typical for the given species.

5.I was awakened by a hysterical barking of Laika. “If you want out”, I said angrily, “there’s no need for all that fuss”.

6.His face was glowing with anger and Stephen felt the glow rise on his own cheek.

UNIT 2

Communication: Models, Perspectives

I. NOTES

How Models Help Us Understand Communication

In addition to defining communication, scholars also build models of it. A model is an abstract representation of a process, a description of its structure or function.

Models aid us by describing and explaining a process, by yielding testable predictions about how the process works, or by showing us ways to control the process. Some models fulfill an explanatory function by dividing a process into constituent parts and showing us how the parts are connected. A city’s organizational chart does this by explaining how city government works, and the sociological description allows us to see the economic and social factors that caused the city to become what it is today.

|

|

|

Other models fulfill a predictive function. Traffic simulations and population growth projections function in this way. They allow us to answer “if... then” questions. If we add another traffic light, then will we eliminate gridlock? If the population keeps growing at the current rate, then what will housing conditions be in the year 2020? Models help us answer questions about the future.

Finally, models fulfill a control function. A street map not only describes the layout of a city but also allows you to find your way from one place to another and helps you figure out where you went wrong if you get lost. Models guide our behavior. They show us how to control a process.

Models are useful, but they can also have drawbacks. In building and using models, we must be cautious. First, we must realize that models are necessarily incomplete because they are simplified versions of very complex processes. When a model builder chooses to include one detail, he or she invariably chooses to ignore hundreds more.

Second, we must keep in mind that there are many ways to model a single process. Unfortunately, when we study complex processes, we can never be one hundred percent certain we understand them. There are many “right answers,” all equally valuable but each distinct. Although this may be confusing at first, try thinking of it positively. Looking for single answers limits you intellectually; accepting multiple answers opens you to new possibilities.

Finally, we mustn’t forget thatmodels make assumptions about processes. It’s always important to look “below the surface” of any model to detect the hidden assumptions it makes.

It All Depends on Your Point of View: Three Perspectives

A perspective is a coherent set of assumptions about the way a process operates. The first three models we will look at are built on different sets of assumptions. The first model takes what is known as a psychological perspective. It focuses on what happens “inside the heads” of communicators as they transmit and receive messages. The second model takes a social constructionist perspective. It sees communication as a process whereby people, using the tools provided by their culture, create collective representations of reality. It emphasizes the relationship between communication and culture. The third model takes what is called a pragmatic perspective. According to this view, communication consists of a system of interlocking, interdependent “moves,” which become patterned over time. This perspective focuses on the games people play when they communicate.

|

|

|

Communication as Message Transmission

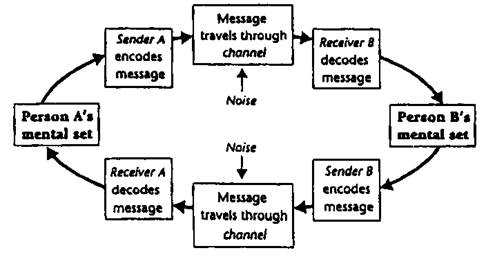

Most models and definitions of communication are based on the psychological perspective. They locate communication in the human mind and see the individual as both the source of and the destination for messages. Figure 2.1 illustrates an example of a psychological model.

In a psychological model, messages are filtered through an individual’s store of beliefs, attitudes, values, and emotions.

Figure 2.1 – The Psychological Model of Communication

Elements of a Psychological Model

The model in Figure 2.1 depicts communication as a psychological process whereby two (or more) individuals exchange meanings through the transmission and reception of communication stimuli. According to this model, an individual is a sender/receiver who encodes and decodes meanings. John has an idea he wishes to communicate to Clare. John encodes this idea by translating it into a message that he believes Clare can understand. The encoded message travels along a channel, its medium of transmission, until it reaches its destination. Upon receiving the message, Betty decodes it and decides how she will reply. In sending the reply, she gives Adam feedback about his message. Adam uses this information to decide whether or not his communication was successful.

During encoding and decoding, John and Clare filter messages through their mental sets. A mental set consists of a person’s beliefs, values, attitudes, feelings, and so on. Because each message is composed and interpreted in light of an individual’s past experience, each encoded or decoded message has its own unique meaning. Of course, partners’ mental sets can sometimes lead to misunderstandings. The meanings John and Clare assign to a message may vary in important ways. If this occurs, they may miscommunicate. Communication can also go awry if noise enters the channel. Noise is any distraction that interferes with or changes a message during transmission. Communication is most successful when individuals are “of the same mind” – when the meanings they assign to messages are similar or identical.

Let’s look at how this process works in a familiar setting, the college lecture. Professor Brown wants to inform his students about the history of rhetoric. Alone in his study, he gazes at his plaster-of-Paris bust of Aristotle and thinks about how he will encode his understanding and enthusiasm in words. To encode successfully, he must guess about what’s going on in the students’ minds. Although it’s hard for him to imagine that anyone could be bored by the history of rhetoric, he knows students need to hear a “human element” in his lecture. He therefore decides to include examples and anecdotes to spice up his message.

Brown delivers his lecture in a large, drafty lecture room. The microphone he uses unfortunately emits shrill whines and whistles at inopportune times. That he also forgets to talk into the mike only compounds the noise problem. Other sources of distraction are his appearance and nonverbal behavior. When Brown enters the room, his mismatched polyester suit and hand-painted tie are fairly presentable, but as he gets more and more excited, his clothes take on a life of their own. His shirt untucks itself, his jacket collects chalk dust, and his tie juts out at a very strange angle. In terms of our model, Smith’s clothes are too noisy for the classroom.

Despite his lack of attention to material matters and his tendency toward dry speeches, Brown knows his rhetoric, and highly motivated students have no trouble decoding the lecture. Less-prepared students have more difficulty, however. Brown’s words go “over their heads.” As the lecture progresses, the students’ smiles and nods, their frowns of puzzlement, and their whispered comments to one another act as feedback for Smith to consider.

Brown’s communication is partially successful and partially unsuccessful. He reaches the students who can follow his classical references but bypasses the willing but unprepared students who can’t decode his messages. And he completely loses the seniors in the back row who are taking the course pass/fail and have set their sights on a D minus. Like most of us, some of the time Brown succeeds, and some of the time he fails.

Improving Faulty Communication

According to the psychological model, communication is unsuccessful whenever the meanings intended by the source differ from the meanings interpreted by the receiver. This occurs when the mental sets of source and receiver are so far apart that there is no shared experience; when the source uses a code unfamiliar to the receiver; when the channel is overloaded or impeded by noise; when there is little or no opportunity for feedback; or when receivers are distracted by competing internal stimuli.

Each of these problems can be solved. The psychological model points out ways to improve communication. It suggests that senders can learn to see things from their receivers’ points of view. Senders can try to encode messages in clear, lively, and appropriate ways. They can use multiple channels to ensure that their message gets across, and they can try to create noise-free environments. They can also build in opportunities for feedback and learn to read receivers’ nonverbal messages.

Receivers too can do things to improve communication. They can prepare themselves for a difficult message by studying the subject ahead of time. They can try to understand “where the speaker is coming from” and anticipate arguments. They can improve their listening skills, and they can ask questions and check their understanding. All of these methods of improving communication are implicit in the model in Figure 2.1.

Criticizing the Psychological Perspective

Although the psychological model is by far the most popular view of communication, it poses some problems, which arise from the assumptions the psychological perspective makes about human behavior.

First, the psychological model locates communication in the psychological processes of individuals, ignoring almost totally the social context in which communication occurs, as well as the shared roles and rules that govern message construction.

Second, in incorporating the ideas of channel and noise, the psychological model is mechanistic. It treats messages as though they are physical objects that can be sent from one place to another. Noise is treated not as a message, but as a separate entity that “attacks” messages. The model also assumes that it is possible not to communicate, that communication can break down.

|

|

|

Finally, the psychological model implies that successful communication involves a “meeting of the minds.” The model suggests that communication succeeds to the extent that the sender transfers what is in his or her mind to the mind of the receiver, thereby implying that good communication is more likely to occur between people who have the same ideas than between those who have different ideas. This raises some important questions: Is it possible to transfer content from one mind to another? Is accuracy the only value we should place on communication? Is it always a good idea to seek out people who are similar rather than different? Some critics believe the psychological model diminishes the importance of creativity.

Communication as World Building

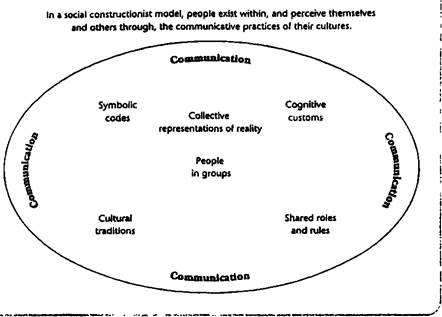

The social constructionist perspective takes a very different view of communication. In this view communication becomes a means of world building. Figure 2.2 illustrates an example of a social constructionist model. According to this model, communication is not something that goes on between individuals; instead, communication is something that surrounds people and holds their world together. Through communication, social groups create collective ideas of themselves, of one another, and of the world they inhabit.

Figure 2.1 – The Social Constructionist Model

Elements of a Social Constructionist Model

According to the social constructionist model, communication is a process whereby people in groups, using the tools provided by their culture, create collective representations of reality. The model specifies four of these cultural tools: languages, or symbolic codes; the ways we’ve been taught to process information, or cognitive customs; the beliefs, attitudes, and values that make up our cultural traditions; and the sets of roles and rules that guide our actions. These tools shape the ways we experience and talk about our world.

The social constructionist perspective maintains that we never experience the world directly. Rather, we take those parts of it that our culture makes significant, process them in culturally recognized ways, connect them to other “facts” that we know, and respond to them in ways our culture considers significant. According to this perspective, we construct our world through communication.

This perspective points out that most of what we know and believe about the world comes to us through communication rather than through direct experience. If everyone around us talks about the world in a certain way, we are likely to think of the world in that way and fail to question whether we are seeing things accurately. Thus, when we later encounter people who communicate in different ways, we will have problems during interaction.

Let’s take an example. Eric has been with his company for thirty years and has five more to go until retirement. When he first started working, there were very few women in managerial positions, but now he finds himself working with many women managers. Eric thinks of himself as fair-minded and easygoing. He has nothing against the fact that “girls” are now moving up in the company, but he does finds it hard to understand why they get so upset over “nothing.” When he calls his female secretary “Honey,” (which he’s done for twenty years), he doesn’t understand the prickly reaction of his new colleague Cindy. After all, he’s just trying to be nice. It’s the way he always talks to women.

Cindy is fresh out of business school and eager to make her way in the professional world. She is appalled by Eric’s behavior. When she hears the way he talks to his secretary, she feels embarrassed and demeaned herself. Furthermore, when Eric treats Cindy like an idiot by explaining everything to her as though she were a child, her blood boils. Cindy has come of age in a time when discussions of feminism and sexism are common. She’s sensitive to issues Eric doesn’t even notice.

|

|

|

Eric’s attempts to communicate with Judy fail because the two colleagues don’t share collective representations of reality. When Eric was growing up, no one talked about sexism and sexual harassment, so for him these concepts have limited meaning. His views of male/female roles used to work, but now they are outmoded. As a result he says things that are completely inappropriate in a modem office. In a very real way, Eric and Cindy live in two completely different worlds.

Improving Our Social Constructions

The social constructionist model emphasizes that we should take responsibility for the things we talk about and the way we talk about them. Our constructions of reality, according to the model, often distort our communication. Thus, we may accept cultural myths and stereotypes without thinking. Given the fact that symbols have the power to control us, it is useful to develop the critical ability to “see through” cultural constructions and to avoid creating them through our own talk. The ability to decipher our biases is a useful skill.

And whereas the psychological model suggests that individuals create communication, the social constructionist model suggests the opposite, that communication creates individuals. To be successful communicators, it maintains, we must be willing to follow cultural rules and norms. We must take our parts in the social drama our culture has laid out for us. We must also carefully consider whether those roles enhance our identities or inhibit them. If a role is outmoded or unfair to others, we must be willing to abandon it and find a new and more appropriate way of communicating.

Criticizing the Social Constructionist Perspective

For many of you, this model may seem to depart radically from commonsense ideas about communication. To say that we live in a symbolic rather than a physical, world seems to contradict our most basic notions about the nature of reality. For if we can never gain access to reality but can only experience constructions of it, then how can we tell the difference between truth and illusion? The social constructionist model raises important philosophical questions as it emphasizes a relationship recognized since ancient times: the relationship between rhetoric and truth.

Another troublesome aspect of the social constructionist position is that it defines good communication as socially appropriate communication. Scholars who take this perspective often talk of humans as social performers. To communicate successfully, one acts out a social role over which he or she has little control. For many, this view implies that the good communicator is a social automaton rather than a sincere and spontaneous self. Many people criticize the social constructionist perspective because it places too much emphasis on the social self and not enough on the individual self.

Communication as Patterned Interaction

The third model takes yet another view of communication. Instead of focusing on individual selves or on social roles and rules, this perspective centers on systems of behavior. It suggests that the way people act when they are together is of primary importance, and it urges us to look carefully at patterns that emerge as people play the communication game.

Elements of a Pragmatic Model

According to the pragmatic view, communication consists of a system of interlocking, interdependent behaviors that become patterned over time. Scholars who take a pragmatic approach argue that communicating is much like playing a game. When people decide to communicate, they become partners in a game that requires them to make individual “moves” or acts. Over time, these acts become patterned, with the simplest pattern being a two-act sequence called an interact. One of the reasons certain acts are repeated is that they result in payoffs for the participants. Over the course of the game, players become interdependent because their payoffs depends on their partners’ actions. This analogy between communication and a game is illustrated in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 – The Pragmatic Model of Communication

| move | A’s moves | B’s moves |

| .................. | B offends A | |

| A ignores B | B repeats offense | |

| A challenges B | B ignores A | |

| A reissues challenge | B offers apology | |

| A accepts apology | B thanks A | |

| A changes subject | .................. |

In a pragmatic model, communication is seen as a game of sequential, interlocking moves between interdependent partners. Each player responds to the partner’s moves in light of his or her own strategy and in anticipation of future action. Some moves are specific to this game, and others are common gambits or strategies. All moves make sense only in the context of the game. Outcomes, or payoffs, are a result of patterned “play” between partners.

The analogy between chess and communication holds in a number of ways. First, the game itself, not what goes on around it, is the central concern. Although it is possible to find books on chess that analyse the personality of individual players, most books focus on the structure of the game itself. Who white and black represent is not nearly as important as how they respond to one another. To understand chess, you need to understand the present state of the board and the series of moves that produced it. To understand communication, pragmatists argue, you need to do much the same thing: understand the “moves” people use as they work out their relationship to one another.

Note that in Figure 2.3 the moves are listed sequentially. At every turn, you can see what black did and how white responded. Chess books always list moves in this way, using the exact sequence in which they occurred in the game. It would make no sense to list all the moves of the game randomly. The game consists of ordered, interlocking moves and makes sense only when we follow the sequence. In the same way, an individual act, or isolated behavior, makes sense only in context, that is, when we see it in relationship to previous acts. According to the pragmatic viewpoint, the smallest significant unit of communication is the interact, which consists of two sequential acts. If you merely hear me cry, you know very little about what is happening. To understand what my crying means, you need to know, at the very least, what happened immediately before I cried. I may have become sad or angry, or I may have laughed so hard I began to cry. My crying may be a sincere expression of sorrow, or it may have been a move designed to make you feel sorry for me. The more you know about what happened before I cried, the more you understand the communication game I’m playing.

One of the factors that makes the game analogy appropriate is the interdependence of game players. Each player is affected by what another player does. Players need each other if they are to play. The same is true of communication: A person can’t be a sender without someone to be a receiver, and it’s impossible for a receiver to receive a message without a sender to send it. The dyad, not the individual, is important. Individuals don’t play the communication game; partners (or opponents) do.

In a game every action is important. Every move I make affects you, and every move you make affects me. Even if I refuse to move, I am still playing: I am resigning from or forfeiting the game. This is even more significant in communication, where any response counts as a move. According to the pragmatic perspective, we cannot not communicate. If a friend promises to write to you and doesn’t, his or her silence speaks louder than words. You realize that your friend doesn’t want to continue the relationship. It is impossible not to communicate, just as it is impossible not to behave.

Finally, communication resembles a game in that both result in interdependent outcomes, or payoffs. In chess the payoff is the thrill of victory or the agony of defeat. Communication also has payoffs. Sometimes they are competitive; for example, someone “wins points” by putting down someone else. But more often than not, the payoffs are cooperative. Each person gets something out of playing. In fact, one way to view relationships is as cooperative improvised games. As people get to know one another, they learn to avoid unproductive moves, and they begin to work out patterns of interaction that satisfy both of them. This is what we mean when we say that two people are “working out the rules” of their relationship. They are learning to play the relationship game with style and grace.

Improving Unhealthy Patterns

According to the pragmatic approach, the best way to understand and improve communication is to describe the forms or patterns that the communication takes. If these patterns are destructive, then the players should be encouraged to find more productive ways of playing the communication game. Let’s say that Bill and Laura are having problems communicating and decide to go to a communication counselor for help. The counselor taking a pragmatic approach will try to uncover the communication patterns that are the root of George and Martha’s problems.

In the beginning, Bill may explain the problem by blaming Laura. “Her need for attention is so great,” he may say, “that I’m forced to spend all my time catering to her. This makes me so mad that I have to get out of the house. She can’t seem to understand that I need my privacy. She’s demanding and irrational.” Of course, Laura has her own version of events, which may go something like this: “He’s so withdrawn, I can’t stand it. He never pays any attention to me. I have to beg to get a moment of his time, and when he does give it, he gets angry. Bill is cold and unreasonable.” Without help, Bill and Laura will each continue to blame the other. Laura may blame Bill’s mother for making him the way he is. Bill may decide that Laura has a personality flaw.

The pragmatic therapist isn’t interested in exploring background issues. Instead, the therapist tries to identify the behavior pattern that is causing the problem. In this case, Bill’s and Laura’s responses to one another are ineffective and are exacerbating the problem. The therapist will help Bill and Laura work out a more effective set of moves that will make them both happy.

Perhaps the most important thing the pragmatic theorist tells us is that to understand communication, we should focus on interaction rather than on personality. When you get into an interpersonal conflict (and it’s in the interpersonal and small-group arena that the pragmatic model seems to fit best), how often do you examine the pattern of events that led up to the conflict? Chances are, you don’t do so very often; instead, you look for a personality explanation. When you and your roommate have problems communicating, you probably don’t ask yourself, “What do I do that causes her to respond the way she does?” Instead, you try to figure out what’s wrong with her. This is not the most productive solution to the problem.

Criticizing the Pragmatic Perspective

The principal problem with the pragmatic viewpoint is that it holds that both personality and culture are irrelevant. Pragmatists steadfastly refuse to ask why people act as they do. They dismiss factors such as intentions, desires, needs, and so on. They are interested only in how sets of interacts pattern themselves. They also have little to say about the cultural context surrounding interaction. Look again at Figure 2.3, and notice that only what happens on the board is important. What happens outside the world of the game is never considered. Who the players are, where the game is played, and what other players are doing are all irrelevant questions.

Summary and Additional Perspectives

The three communication models we’ve reviewed, although they are different, all contribute to our understanding of communication. They show us that to understand communication, we must look at three factors: the individuals with whom communication originates, the social context within which communication arises, and the interaction through which communication is realized.

2015-08-21

2015-08-21 1382

1382