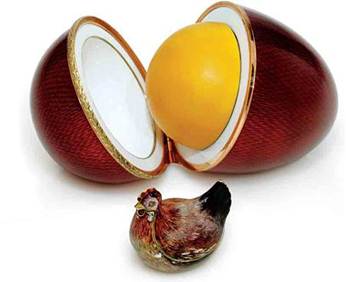

THE ROSEBUD EGG: A FABERGÉ IMPERIAL EASTER EGG PRESENTEDBY EMPEROR NICHOLAS II TO HIS WIFE THE EMPRESS ALEXANDRA FEODOROVNA AT EASTER 1895,WORKMASTER MICHAEL PERCHIN, ST. PETERSBURG

Enameled translucent strawberry red over a 18eweled18e ground and divided into four vertical panels by diamond-set borders, each panel of the hinged top applied with green gold laurel wreaths tied with red gold and diamond-set ribbons, each panel of the lower portion of the egg applied with diamond-set arrows entwined by green gold laurel garlands tied with red gold ribbons and pinned by diamonds, the top of the egg mounted with a table diamond beneath which is set a portrait miniature of Tsar Nicholas II, the base of the egg enameled with the date 1895 below a diamond, the egg opening to reveal a velvet-lined interior fitted with a rosebud with hinged petals enameled yellow and with green enamel leaves, marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster, Fabergé in Cyrillic and assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold.

Enameled translucent strawberry red over a 18eweled18e ground and divided into four vertical panels by diamond-set borders, each panel of the hinged top applied with green gold laurel wreaths tied with red gold and diamond-set ribbons, each panel of the lower portion of the egg applied with diamond-set arrows entwined by green gold laurel garlands tied with red gold ribbons and pinned by diamonds, the top of the egg mounted with a table diamond beneath which is set a portrait miniature of Tsar Nicholas II, the base of the egg enameled with the date 1895 below a diamond, the egg opening to reveal a velvet-lined interior fitted with a rosebud with hinged petals enameled yellow and with green enamel leaves, marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster, Fabergé in Cyrillic and assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold.

On October 20, 1894, Tsar Alexander died. Just a few weeks later, on November 14, his son married Nicholas Alexandra Feodorovna, formerly Princess Alix Victoria Helene Luise Beatrix of Hesse-Darmstadt. The homesick young bride missed, among other things, the roses in her homeland. In Darmstadt, there was a famous rose garden called “Rosenhöhe,” established in 1810 by Grand Duchess Wilhelmine of Hesse, Princess of Baden (1788-1836) and designed by the Swiss garden architect Zeyher. In 1894, Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig, Alexandra’s brother, built the Palais Rosenhöhe there (destroyed 1944) and had the garden redesigned, adding the Rosendom. To this day, the Rosenhöhe remains one of the most beautiful rose gardens in Germany. The Rosebud Egg, then,was an ideal gift for Nicholas to give to his adored wife for their first Easter together. 1

With its bonbonnière shape, its chased gold laurel swags, its diamond-set tied ribbons and arrows and its red 18eweled18e enamel ground, the egg is a perfect rendition of an eighteenth-century symbol of Love. The Rosebud Egg is also the quintessence of Fabergé’s new Neo-Classical style. Neoclassicism, inspired by Antiquity, was developed during the reign of Louis XVI as a reaction against the exuberant Rococo idiom of the Louis XV period. As in the case of the eighteenth century, nineteenth century Neo-Classicism followed the Neo-Rococo of the 1880s and is best seen in Michael Perchin’s early work for the Fabergé firm. In Paris the new Neo-Classical style was embraced by those few who eschewed the all-powerful influence of Art Nouveau. The two contrasting styles of Neo-Classicism and of Art Nouveau are clearly represented in the oeuvre of the great firms of Cartier and Lalique. On one hand, Cartier, ensconced in the firm’s new rue de la Paix premises, did not exhibit at the 1900 Exposition Universelle and totally negated the much fêted symbolist movement. On the other hand stood the extraordinary series of jewels created by Lalique for Calouste Gulbenkian, shown to much public acclaim at the 1900 World Fair. The light touch and elegance of Cartier’s novel Neo-Classical style was underlined by the firm’s use of platinum, a Cartier innovation. Even contemporary music, such as Debussy’s Pelleas et Mélisande of 1900-1902, reflects the influence of Neo-Classicism.

The floral form of the surprise is an eighteenth-century concept continued into the nineteenth century. Such enameled flowers, popular at the time as watch-cases or perfume bottles, were generally produced in Geneva. A Swiss rose with spring-loaded pink enamel petals opening to show a watch was made in Geneva in the 1830s. 2 Fabergé’s yellow rose originally opened to reveal a crown containing a pear-shaped ruby pendant as further symbols of Imperial authority and of Love.

This egg is listed on Fabergé’s invoice as:

“31 March. Red enamel egg with crown. St. Petersburg,May 9, 1895 3250 r.” 3

The Rosebud Egg, the first Imperial Easter Egg received by the new Empress, was kept by her, along with all the early Fabergé Easter eggs, in a corner cabinet of the Imperial couple’s private apartment at the Winter Palace, between a door leading into the bedroom and a window. There the egg and its surprise were minutely described in 1909 by the Inspector of Premises of the Imperial Winter Palace as containing “ an Imperial crown entirely made of rose-cut diamonds with two cabochon rubies. ” 4

The Rosebud Egg was first exhibited in 1935 in London as owned by a Mr. Parsons, still containing its surprise of a diamond-set crown with a pendant ruby. In 1953 Kenneth Snowman included an archival photograph of it and listed its current whereabouts as unknown. Lost for four decades, rumor had it that the egg had been seriously damaged, if not destroyed, in a marital dispute. Telltale damage to the enamel (expertly repaired since) enabled Malcolm Forbes, who acquired the egg in 1985 from the Fine Art Society, London, to ascertain the egg’s authenticity

4) THE SPRING FLOWERS EGG

A FABERGÉ GOLD, PLATINUM, ENAMEL, HARDSTONE AND JEWELED EASTER EGG,WORKMASTER MICHAEL PERCHIN, ST. PETERSBURG, PRE- 1899

Enameled translucent strawberry red over a 19eweled19e ground and applied with neorococo gold scrolls and foliage, opening along a vertical diamond-set seam to reveal a removable diamond-set platinum miniature basket of wood anemones, the flowers with chalcedony petals and demantoid pistils, the egg fastening at the top by means of a diamond-set clasp, the lobed bowenite base with a diamond-set girdle and with a gold rim pierced with neorococo shell work and scrolls, marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster, Fabergé in Cyrillic and assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold, also with scratched inventory number 44374 or possibly 44474.

Enameled translucent strawberry red over a 19eweled19e ground and applied with neorococo gold scrolls and foliage, opening along a vertical diamond-set seam to reveal a removable diamond-set platinum miniature basket of wood anemones, the flowers with chalcedony petals and demantoid pistils, the egg fastening at the top by means of a diamond-set clasp, the lobed bowenite base with a diamond-set girdle and with a gold rim pierced with neorococo shell work and scrolls, marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster, Fabergé in Cyrillic and assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold, also with scratched inventory number 44374 or possibly 44474.

The Spring Flowers Egg, hallmarked with head workmaster Michael Perchin’s “early” mark, is struck with the St. Petersburg’s assay mark for before 1899 and appears to bear a scratched number 443 (or 4) 74, which may or may not be Fabergé’s inventory number. Its original fitted case is stamped with Fabergé’s Imperial Warrant and the addresses of St. Petersburg, Moscow and London. These facts seem to be in apparent contradiction. The hallmark dates the egg to before 1899, the original case to after 1903, after the opening of the London Branch. Inventory numbers do not generally appear on Imperial eggs.

A list of objects dated 14-20 September 1917 transferred from the Dowager Empress’s Anichkov Palace to the Kremlin Armory and signed by Major-General Yerechov, 1 mentions a “purse of gilt silver in the form of an egg covered with red enamel, with a sapphire” and, separately, “a basket of flowers with diamonds,” which probably correspond to this egg and its surprise. It was sold by the State firm Antikvariat in charge of the disposals of Russian Imperial treasure, to an unspecified buyer in 1933 for 2,000 rubles ($1,000), later sold by A La Vieille Russie to the Long Island collector Lansdell Christie, and again by the same New York dealers to Malcolm Forbes as an Imperial egg in 1966. It was exhibited as an Imperial Easter egg twice at the Metropolitan Museum in 1961 and 1996 and at the seminal exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1977, and, up to 1993 has been published by all leading specialists, including Bainbridge (1949), Snowman (1962, 1963, 1964, 1972), Habsburg (1979, 1987, 1993, 1996), Solodkoff (1979, 1984, 1988, 1995) and Hill (1989) as part of the series of Imperial eggs. Recently, Muntian (1995) and Fabergé/Proler/Skurlov (1997) have excluded the Spring Flowers Egg from the list of presents made by the last two Tsars. Muntian, based on the 1917 inventory of the Anichkov Palace, now believes that it belonged to the Dowager Empress and assumes that it was presented to her by a relative or close friend.

With its decoration of scrolls and rocaille, the Spring Flowers Egg is a typical example of Michael Perchin’s early Neo-Rococo style, probably dating from the late 1880s or early 1890s. This date is borne out by the early form of Perchin’s initials. Inexplicably, the basket of wild anemonies in this early egg is virtually identical to the surprise contained in the Winter Egg designed by Alma Pihl for Albert Holmström in 1913.

5)  The Scandinavian Egg

The Scandinavian Egg

THE SCANDINAVIAN EGG: A FABERGÉ VARICOLOR GOLD AND TRANSLUCENT ENAMEL EASTER EGG,WORKMASTER MICHAEL PERCHIN, ST. PETERSBURG, 1899-1903

Enameled translucent strawberry red over a 21eweled21e ground, bisected by a red gold band applied with a chased green gold border of laurel, the egg opening horizontally to reveal a white enamel interior resembling the white of an egg and a matte yellow enameled “yolk,” the yolk hinged and opening to reveal a suede fitted compartment holding a naturalistically enameled gold hen painted primarily in shades of brown with touches of gray and white, when lifted at the beak the hen opens horizontally, the hinge concealed in the tail feathers, marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster and 56 standard for 14 karat gold, also with scratched inventory number 5356.

The present Easter egg is one of a series of hen-and-egg creations by Fabergé, of which a small number have survived. The nearest parallel is the more lavish Kelch Hen Egg (p. 288), which closely resembles the present example but for the fact that it lies on its side and is not embellished with diamonds. Both eggs are otherwise virtually identical with their red 21eweled21e enamel exteriors, their opaque white enamel “whites,” their opaque yellow enamel “yolks” and their varicolored painted hens with rose-cut diamond eyes. Both are by Michael Perchin and date from between 1899 and 1903. Other naturally shaped Easter eggs include the First Hen Egg of 1885 (p. 74), the first of the Imperial series and two unmarked eggs, one of lapis lazuli containing a crown in its yolk (Cleveland Museum of Art) 1 and an egg with platinum shell, hen, crown and ring, attributed to Erik Kollin (Fine Arts Museum, New Orleans), 2 which is undoubtedly not Russian.

The present egg was discovered in an Oslo bank safe by the present author in 1980 among the effects of Maria Quisling (1900-1980), the widow of Vidkun Quisling (1887-1945). They lived in a mansion at Bygdøy in Olso, which he called Gimle after the Hall of Gimle, the most beautiful place on earth according to Norse mythology.

Vidkun Quisling was the son of Jon Quisling, a Lutheran priest and well-known genealogist. A major in the Norwegian army, Quisling served as Military Attaché in Petrograd in 1918-1919, where he probably acquired the present egg, and in Helsinki in 1919-1920. He later worked with Fridtjof Nansen in the Soviet Union during the famine in the 1930s. Quisling served as Minister of Defence in 1931-1933 and founded the fascist Norwegian Socialist party, the Nasjonal Samling, in 1933 together with State Attorney Johann Bernhard Hjort. He became the leader of this originally religiously rooted party, which became outspokenly pro-German and anti-Semitic from 1935 onward.When Hitler’s armies invaded Norway on April 9, 1940, Quisling supported the Führer’s new Reichskommissar Joseph Terboven and became Prime Minister in 1942. After the German surrender in 1945, he was tried as a traitor and executed by firing squad.

The origin of the hen-in-an-egg Easter present harks back to the beginning of the eighteenth century. Three very similar 22eweled eggs have survived, each formerly in a royal treasury. The best known, due to its traditional association with Fabergé’s First Hen Egg, is an egg in the Chronological Collection of the Queen of Denmark at Rosenborg Castle (p. 84), Copenhagen; another is in the Kunsthistorische Museum, Vienna, as part of the Habsburg Collections; yet another is listed among the treasures of the Grünes Gewölbe, the Green Vaults in the Castle of the Elector-Kings of Saxony (Private Collection, both illustrated on p. 84). All three have yolks containing hens, which open to reveal a crown within which nestles diamond-set ring. All three are thought to have originated in Paris, dating from the 1720s. 3 The theme remained popular throughout the nineteenth century.

As the present egg is not listed among the Imperial presents, it was probably privately commissioned in St. Petersburg.Other documented, privately owned eggs by Fabergé include the series of seven Kelch eggs, of which the 1898 Kelch Hen Egg (p. 288) was the first and the 1904 Kelch Chanticleer Egg (p. 306) the last; the Nobel Ice Egg 4 circa 1914; the 1902 Duchess of Marlborough Egg; and the 1907 Sandoz Youssoupov Egg 5.

Эмаль

Эмаль (франц. Email, от франкск., smeltan — плавить), стеклоэмаль, преимущественно глухие (непрозрачные), окрашенные в различные цвета окислами металлов, легкоплавкие стекла, наплавляемые одним или несколькими тонкими слоями (эмалирование) на металл. Э. Часто называют также легкоплавкие глухие белые или окрашенные глазури, применяемые для покрытия и художеств, росписи керамических и стеклянных изделий. Основными компонентами почти всех Э. Являются двуокись кремния SiO2, борный ангидрид B2O3, окись алюминия Al2O3, окись титана TiO2, окислы щелочных и щёлочноземельных металлов, свинца, цинка, некоторые фториды и др. Э. Принято делить на грунтовые и покровные. Грунтовые Э., в которые входят сцепляющие вещества (главным образом окислы кобальта и никеля), служат для нанесения слоя, который хорошо сцепляется с металлом и является промежуточным между покровным слоем Э. И металлом. Покровные Э., которые хорошо сцепляются с металлом, наносят без грунтовой Э. Для приготовления Э. Смесь полевого шпата, песка или кварца, плавикового шпата, буры, борной кислоты, соды, селитры, криолита и другие сплавляют в печах при 1150—1550 °С и выливают в воду для грануляции. Гранулы размалывают в шаровых мельницах в присутствии воды, глины и других материалов для получения устойчивой суспензии мелких частиц, т. н. Эмалевого шликера. Металл сначала покрывают грунтовым шликером, сушат и обжигают (500—1400 °С, в зависимости от покрываемого металла), после чего наносят покровную Э. В один-два слоя с обжигом каждого слоя отдельно. Шликер наносят погружением, обливом, пульверизацией и электростатически, проводят в периодически или непрерывно действующих печах.

Э. Защищает металл от коррозии и придает ему красивый внешний вид. Наносят Э. В основном на чугун и сталь, однако в ряде случаев и на медные, алюминиевые и серебряные изделия, а также изделия из различных сплавов. Основные области применения эмалированных металлов — пищевая, химическая, фармацевтическая, электротехническая промышленность, строительство. Жароупорные и высококорозионностойкие эмалевые покрытия используются в реактивных двигателях; в аппаратах для особо агрессивных сред; при термообработке и горячей деформации специальных сплавов.

Эмали художественные — украшение Э. Золотых, серебряных и медных изделий (сосудов, ювелирных изделий и пр.). Э. — древнейшая техника, применяемая в ювелирном искусстве: холодная (без обжига) и горячая, при которой окрашенная окисями металлов пастозная масса наносится на специально обработанную поверхность и подвергается обжигу, в результате чего появляется стекловидный цветной слой. Э. Различают по способу нанесения и закрепления на поверхности материала. Перегородчатые Э. Заполняют ячейки, образованные тонкими металлическими перегородками, припаянными на металлическую поверхность ребром по линиям узора,—передают четкие линии контура. Выемчатые Э. Заполняют углубления (сделанные резьбой, штамповкой или при отливке) в толще металла отличаются большой интенсивностью цвета. Э. (чеканному, литому), прозрачная и глухая, позволяет передать объемные формы, достигать живописных эффектов, т. к. при плавлении эмалевая масса стекает с высоких частей рельефа и появляются сочетания прозрачных и непрозрачных пятен, дающие ощущение теней. В расписной (живописной) Э. Изделие из металла покрывается Э. И по ней расписывается эмалевыми красками (с 17 в. — огнеупорными). Э. Бывает также по скани (филиграни), гравировке, с золотыми и серебряными накладками. Наиболее ранние из дошедших Э. — золотые украшения и амулеты Древнего Египта, близкие по технике к перегородчатым. Лучший образец ранней европейской перегородчатой Э. — облицовка стенок алтаря в церкви Сант-Амброджо в Милане (мастер Вольвиниус 9 в.). В Византии в 10—12 вв. была развита перегородчатая Э. На золоте. К началу 12 в. сложились европейские школы Э.: маасская — в долине р. Маас, в Лотарингии (мастера Годфруа де Клер и Николай из Вердена) рейнская с Кельном во главе (мастера монахи Эйльбертус и Фридерикус) школа лиможской эмали. Европейские Э. В основном украшавшие церковную утварь, органически связаны с убранством соборов, витражами. С конца 14 — в начале 15 вв. в технике Э. Выполнялись предметы светского характера. Глухие и непрозрачные Э. Сменяются прозрачными Э. По гравировке с введением золотых линий и накладок. В 18 в. на первый план выдвинулись эмалевая портретная миниатюра и живопись, стилистически близкие станковой живописи. Трудоёмкая техника Э. Пришла в упадок в 19 в. и возродилась лишь в эпоху господства стиля «модерн» в Париже, Брюсселе, Вене — изготовление украшений, табакерок, вееров в сочетании с драгоценными камнями, жемчугом и пр. (К. Поплен, Р. Лалик, П. Грандом). В Китае Э. Известны с 7 в., получили большое развитие в 14—17 вв. Э., украшающие детали холодного оружия, коробочки, табакерки и т. п. Символическими растительными мотивами, изображениями птиц и животных. На территории СССР Э. Изготовлялись в 3 — 5 вв. в Приднепровье (браслеты, фибулы с красной, голубой, зелёной и белой Э). Сохранились перегородчатые Э Киевской Руси 11 в. Влияние Византии сказалось на русских перегородчатых Э. 12-13 вв. на серебре и золоте и средневековой грузинской Э. На золоте, отличавшейся от византийской Э. Менее тонкой технической проработкой, от русских — более ярким цветом (Хахульский складень, 12 в., Музей искусств Грузинской ССР, Тбилиси). В 16-17 вв. у московских мастеров получила распространение Э. По скани — прозрачная многоцветная Э. Густых насыщенных тонов на золотых изделиях (мастера Оружейной палаты И. Попов и др.), по сюжетам и орнаментике близкая украшению рукописей того же времени. В 17 в. в Сольвычегодске расцвело искусство расписной Э. («усольской»). Развитие расписной Э. По меди удешевило эмалевые изделия и расширило круг предметов, украшенных Э. (помимо культовых предметов, ларцы, чарки, коробочки для румян, флаконы, ложки и т. д.). В 18-19 вв. в Ростове Великом изготовлялись иконы и другие изделия в технике расписной Э. В 18 в. развилась эмалевая портретная миниатюра (Г. С. Мусикийский, А. Г. Овсов, И. П. Рефусицкий, живописец А. П. Антропов). М. В. Ломоносов разработал новую палитру эмалевых красок из отечественных материалов; был учрежден эмальерный класс в петербургской АХ (впервые упомянут в 1781). В конце 19 — начале 20 вв. изделия с Э. Изготовляли фирмы Фаберже, Хлебникова, Овчинникова, Грачева.

В СССР выпускают изделия с расписной Э., с Э. По скани, по гравировке, штампованному рельефу и др. Крупным центром производства Э. Является фабрика «Ростовская финифть» (в Ростове-Ярославском), продолжающая идущую с 18 в. традицию живописной Э. (броши, пудреницы, коробочки), в основном с декоративными цветочными композициями, а также сюжетными миниатюрами (мастера А. М. Кокин, В. В. Горский, И. И. Солдатов, В. Г. Питслин и др.).

2015-04-12

2015-04-12 377

377