MARY CATHERINE BASEHEART,

S.C.N.** and LINDA LOPEZ McALISTER with WALTRAUT STEIN*

I. BIOGRAPHY1*

Edith Stein was born on October 12, 1891 in Breslau, East Silesia (now Wroclaw, Poland), the youngest of the eleven children of Siegfried and Auguste Stein. She grew up in a strict Jewish home where her mother was the strong, pious, guiding figure. Her father, a businessman, died when Edith was two years old and her mother continued to run the family lumber business with the help of her children. The home, though strict, was a warm one and Edith’s childhood was filled with religious observations, family celebrations, visits to and from grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins and friends. At age thirteen Edith began to doubt her Jewish faith, and became, for all intents and purposes, an atheist.

After completing her secondary school education, Edith went to the University of Breslau where she studied German language and literature, philosophy and history. Upon discovering Edmund Husserl’s philosophy in his Logische Untersuchungen (Logical Investigations), she went, in 1913, to the university at Gottingen to join the circle of students around Husserl, who were in the forefront of a new philosophical movement known as phenomenology.2 She desired ardently to discover the truth, and she saw that Husserl’s thought was about reality, undercutting the epistemology of the neo-Kantians. After the outbreak of World War I, many of Husserl’s students were at the front, and Stein’s strong nationalistic feelings moved her to volunteer as a nurse’s aide for the Red Cross, but she returned to her studies after a time. When Husserl left Gottingen for Freiburg, she went with him and wrote her doctoral dissertation entitled Zum Problem der Einfiihlung (On the Problem of Empathy). With the presentation of the dissertation, Stein was awarded the doctorate summa cum laude. Husserl was so impressed by her intellect that he offered to make her his assistant. In this capacity her duties

A History of Women Philo sophers/Volume 4, ed. by Mary Ellen Wait he, 157-187.

© 1995 Kluwer Academic Publishers.

included teaching a course referred to as the “philosophical kindergarten” to prepare new students to work with Husserl, and putting Husserl’s manuscripts for Ideen (Ideas), Vol. II in order by transcribing his shorthand notes into script so that he could work the material over. This proved to be a frustrating assignment for Stein because her hope had been that she and Husserl would be able to work together as colleagues. Husserl shared this idea in theory, but in practice he did not seem interested in their working collaboratively. He did, however, come to depend heavily on the services she provided for him. While the obvious next step for her would have been to habilitate, i.e., to become a faculty member at the university, Husserl was not supportive. He could not, “as a matter of principle,” bring himself to sponsor a woman for habilitation, which would have been a major break with tradition.3 His “solution” was for Stein to stay on as his assistant and find a suitable husband - preferably, one who could also be an assistant to Husserl. As Stein joked, presumably their children would be Husserl’s assistants, too.4 Obviously this situation could not continue indefinitely. Stein had her own life and work to get on with, and had come to feel that she could not bear always being at someone’s back and call, in short, belonging to another human being, even someone as respected as “the Master,” Husserl.5

During this period of Stein’s life other things were happening, too. Her friend, the Gottingen philosopher Adolf Reinach, was killed in the war, and she went to Gottingen to console his widow. When she got there she discovered that this woman was showing amazing strength in her bereavement, as a result of her strong Christian faith which gave her the courage to bear her loss. This example of faith made a profound impression on Edith Stein. Instead of consoling she found herself consoled.

After the winter semester of 1918 she resigned her assistantship and returned to Breslau for a time, before going to Gottingen in Fall of 1919 to attempt, unsuccessfully, to habilitate there. The official reason given for her failure was that she was a woman. In addition, she was told privately that her habilitation thesis might have been upsetting to Dr. Mdller, one of the philosophy professors, so, in order to spare her any possible unpleasantness, the decision was made administratively not even to submit her thesis to the faculty for review.6 At this point Stein returned to Breslau, but she did not just accept this injustice without putting up a fight. She wrote an appeal to the Prussian Ministry for Science, Art and Education, and on February 21, 1920, Minister Becker issued a milestone ruling in response to her appeal, declaring for the first time that “mem-

bership in the female sex may not be seen as an obstacle to habilita- tion” in German universities.7 She did not, however, renew her attempt to habilitate at Gottingen. She wrote to a friend at the time that she did not think the ruling would be of much help to her personally, but that she had sought it as a way of thumbing her nose at “the gentlemen in Gottingen.”8 It did, however, clear the way for women seeking a pro-fessorial career in fields other than philosophy. In philosophy it was another 30 years before the first German woman actually habilitated and took up teaching duties at a German University.9

Much has been written about the fact that many of the phenomenol- ogist philosophers underwent religious conversions or an intensifying of their religious faith during this period.10 Around 1920 Stein read the autobiography of St. Teresa of Avila. When she laid down the book she said to herself, “This is the truth.” She does not tell us what made her see the truth in this account, but it may be that she was searching for the meaning of her own existence. Husserl, with his method of describing the world, had not been able to show her why she was in it. She now found this content for her existence in Roman Catholicism, and on New Year’s Day, 1922, at thirty-one years of age, she was baptized - a step which caused considerable concern on the part of her mother and other family members.

From 1922 until 1932 Stein worked as a lay teacher in a Catholic girls school run by the Dominican Sisters of St. Magdalena in Speyer, and became quite well-known in Catholic educational circles. During this time she wrote a number of treatises on the education of girls, and on professions for women, and other pedagogical issues. From her correspondence during that period it seems that she was very much in demand as a speaker at various conferences on Catholic education. At first she gave up her philosophical work entirely, believing that faith and reason do not mix. But she learned that she did not have to cut herself off from philosophy when she discovered the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas. Once more she took up the study of philosophy, this time that of scholasticism. In order to grasp St. Thomas’s thought, she translated his Quaestiones disputatae de veritate into German, using the language of phenomenology so that he would be intelligible to the contemporary German philosopher. She also wrote original works which attempted a synthesis between Thomistic and phenomenological thought.11 In addition, during this period she began the preliminary work for her book Endliches und Ewiges Sein (.Finite and Eternal Being).

This appears from her letters to have been a full and satisfying time

of life for Stein, but that she viewed it as a time of waiting and that she believed eventually the right opportunity would emerge for her, whatever it might be. In 1931 Stein conferred with Professors Eugen Fink and Martin Heidegger about the possibility of her habilitating at Freiburg; later that year there was talk about her habilitating at the University of Breslau. Nothing came of either of these attempts. Finally, in 1932, she joined the faculty of the German Institute of Scientific Pedagogy in Munster. As a Dozent she held lectures and attracted some students from the university as well as her education students from the Institute.12 Stein’s career in higher education was, however, to be very brief. By the summer semester of 1933, the Nazis had come to power, and, because of her Jewish background, Stein was no longer allowed to meet her classes. Her contract was not renewed for the following year.

One would expect that this turn of events would have been devastating to Stein. One effect it had was to motivate her to write Life in a Jewish Family, a memoir of her childhood, youth and family, in particular her mother, as an antidote to the terrible anti-Jewish propaganda spread by the Nazis. It also moved her to political action in the sense that she appealed to the Pope to issue an encyclical condemning Facism and racism, but this did not happen. Nonetheless she seems to have experienced the loss of her position almost as a positive development. She remarked on several occasions while she was in Munster how foreign the world had become to her during the ten years she spent within the walls of the Dominican convent in Speyer, even though she had been a lay person. In late 1932 she remarked that she must seem strange to more worldly people and that she notices, now that she is out in the world, what an effort it is to be a part of it. She says, “I do not believe that I can ever really do it again.”13 By late in May, 1933 the future course of her life had become clear to Stein and it is one which she welcomed with all her heart. In late June she informed her closest friends that she would be spending the summer in Breslau with her family. There she would have the excruciatingly difficult task of breaking the news to her mother that she intended to enter the Carmelite convent in Cologne- Lindenthal as a postulant on October 15.14 She did so, and six months later she donned the habit of a Carmelite nun and became Sr. Teresia Benedicta a Cruce, OCD.

The Carmelites are a cloistered order devoted to prayer and medita-tion. They may speak with the outside world only through a grille. Stein did not expect to continue her writing after entering the order, but, in fact, she was asked by her superiors to continue her work on

the manuscript entitled “Akt und Potenz,” which was published posthu-mously as Endliches und Ewiges SeinP

By 1938 the Nazi menace was becoming ever greater, and in order to ensure the safety of Stein and of her older sister Rosa, who had also converted to Catholicism and was now serving as the concierge of the convent, it was arranged that they would move to the Carmelite Convent in Echt, Holland.16 But even this was not a sufficient refuge after Hitler marched into Holland, so it was decided that Edith and Rosa must go to Switzerland. The arrangements were slowly put into place, and everything was settled except for the exit visas. But they did not come in time.

On Sunday, July 26, 1942, the Catholic Bishops in Holland issued a pastoral letter condemning the Nazi extermination of the Jews throughout Europe. As an act of revenge for their courageous stand, on August 2 the S.S. made a sweep through the country incarcerating all “non-Aryan Christians.” At five in the afternoon two uniformed S.S. officers appeared at the convent and demanded to speak with Sr. Benedicta. They gave her and Rosa ten minutes to get ready to leave the convent. Sr. Benedicta took Rosa by the hand and said, “Come, we will go for our people.”

They were loaded into a truck and taken, along with 10 or 15 religious and approximately 1000 others to a concentration camp at Amersfoort, and then on to Westerbork. Some of these people were later released so there were eye-witnesses to the events of the next few days. The image that emerges is of Sr. Benedicta plunging in and working to comfort the terrified children and their despairing mothers. She is reported to have remarked, “Until now I have prayed and worked, now I will work and pray.” Seldom saying a word, she moved about tirelessly, doing what she could to comfort and console and to lead the others in prayer. On August 6 she was able to send a brief note to the sisters in the convent in which she asked for clothing, medicine and blankets and told of a transport that was leaving the following day for the East. Two men from Echt had gone to Westerbork to try to see the sisters, and, indeed, they were able to get into the camp and spend some time with them. Sr. Benedicta sent back word to the Convent that they were not to worry, and that she and Rosa were all right. She praised the Jewish relief orga-nization which was working hard, but in vain, to secure the release of this group of Jewish Catholics.

All reports that we have of Sr. Benedicta during this time stress her calm, peaceful manner amidst chaos and despair. When the lists were

read of those prisoners who were to get on the train, Edith and Rosa Stein were among them. They were murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz on August 9, 1942.

Sr. Teresia Benedicta a Cruce was declared a Saint and martyr in the Roman Catholic church by Pope John Paul II on May 1, 1987 in Cologne.

II. PHILOSOPHY**

Edith Stein, philosopher, is not so well-known as Edith Stein, heroic German-Jewish woman, educator, lecturer, feminist, saint, and victim of the Holocaust. Yet it was philosophy that was the axis of her being as it was lived in all of these modes, and anyone who desires to know and understand Stein must know her as a philosopher. The present account attempts a developmental approach, revealing her advances in phenomenology from method to metaphysics, from the realm of mind to that of reality, and from a largely theoretical content to the inclusion of a Weltanauschauung. It would not do justice to her philosophizing simply to present a summary of her thought at the end of her life.

From her early years, Stein was always asking the why of human existence, never satisfied with the ready answers prevalent in her religious and social milieu. Her student days at Breslau, Gottingen, and Freiburg- im-Breisgau were animated by a passionate interest in philosophy and characterized by disciplined study of phenomenology under Edmund Husserl, in company with the famous scholars who engaged him in discussion and dialogue: Max Scheler, Adolf Reinach, Fritz Kaufmann, Roman Ingarden, Hedwig Conrad-Martius, Alexandre Коугё, and Martin Heidegger, to name only a few. After achieving the Ph.D. at Freiburg in 1917, her own philosophy was taking a form that was basically phenomenological but often at variance with views of Husserl in substance, if not in spirit, and she was writing original works of her own. Her questioning soon moved beyond the limits of phenomenology to a broad and deep exploration of the greats in the history of philosophy, particularly Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, but extending also to Plato, Augustine, Descartes, Duns Scotus, as well as contemporary philosophers. In her efforts to construct a body of theory, there is evidence of a strong impulse toward synthesis of phenomenology with what she found true in the philosophy of other times and other schools.

Stein was a prolific writer on a broad range of philosophical subjects,

but only a few of her works were published during her lifetime, largely because of the ban on works by non-Aryan writers after the Nazis came to power. Her dissertation, On the Problem of Empathy, completed under Husserl at the University of Freiburg and published in 191717 is the only full-length philosophical work of hers that has been published in English translation to date18 although others will be forthcoming as part of the project to translate her Works into English.

As has been indicated in the account of her life, Stein and a number of other young students had flocked to Gottingen to study with Husserl because, after reading his Logical Investigations, they seemed to find in his work a turning away from German Idealism toward a new form of realism.19 But in 1913 history was being made in Husserl’s theory. Ideen 720 had just appeared in the Jahrbuch, and many of Husserl’s pupils were quick to realize and resist the impact of his emerging transcendental idealism. Edith Stein was among these.

Stein soon declared her independence implicitly in her own writings, but it should be noted that she was an remained in many ways a true disciple of Edmund Husserl. She appreciated the critical receptivity of mind that came from her philosophical training in examining presup-positions, in weighing without prejudice, and in being open to all phenomena. She used to advantage the method of descriptive analysis of the phenomena of consciousness - the turning to the “intentional object,” of which the subject, the “I” is conscious in its stream of lived experiences. She also affirmed in theory and in practice Husserl’s “eidetic reduction,” that is, the thought act which proceeds from the psychological phenomena to the essence, from fact to essential universality, the process which focuses on the “things” of experience,21 the cogita- tiones and their cogitata, and probes them by way of descriptive analysis. But for Stein these “things” of experience presupposed things of the fact world, the existence of which Husserl “brackets.” She never gave assent to Husserl’s transcendental reduction, the epochi, that is, the suspension of judgment in regard to the transcendent existence of the objective correlates of the cogitata}1 In the foreword to the English translation of her dissertation, Edwin W. Straus remarks on Stein’s existential approach as contrasted with the predominantly epistemological interests of Husserl.23 Although Husserl had taken his starting point from mathe-matics and logic, and questions relating to man were relatively far from him at this time, Stein continued her interests in literature, history, and the humanities, which she had studied at Breslau, and persisted in her desire to discover roots for the empirical science of

psychology. She had originally selected psychology as her major but found it lacking a solid foundation in intellectual principles.

1. Personhood

Stein’s interest in the ontological structure of the human person is the thread that runs through all her work from first to last. Her work on empathy is essentially an investigation of the structure of the psychophysical individual, and the knowledge of empathy emerges as a valuable key to unlock the secrets of personhood. Perhaps this was one reason for her choice of empathy as her subject. Roman Ingarden, who was closely associated with Stein for some years, is of the opinion that she chose empathy as a way of clarifying the theoretical foundation not only of man but also of community.24 She herself tells us her choice was motivated by the desire to fill the gap in the knowledge of what empathy meant when Husserl maintained in his course on Nature and Spirit the necessity of inter subjective experience, which Theodor Lipps termed “empathy.”25

This early work gives insight into the character of Stein’s philoso-phizing and of her use of phenomenological method in arriving at knowledge not only of empathy but also of the human person. It will, therefore, be considered in some detail. Beginning with the assumption that foreign26 subjects and their experience are primordially given to us, she examines the phenomenon of givenness. Like Husserl she attempts to exclude from her investigation at the outset the consideration of anything that is any way doubtful. She raises the possibility of one’s being deceived in regard to the existence of the surrounding world and other subjects and even of the empirical “I.” Unlike Husserl, however, she admits there are difficulties in seeing how it is possible to suspend the positing of existence and still retain the full character of perception.27 One thing she holds cannot be doubted and excluded is her experiencing “I,” the experiencing subject who considers the world and its own person as phenomenon; this “I” is as indubitable and impossible to cancel as experience itself. It is the “I” in the I perceive, I think, I am glad, I wish, and so.

(a) Psycho-Physical Unity. Stein’s next step is to affirm the phenom-enon of foreign psychic life, i.e., of other minds or experiencing subjects external to the “I,” as given in my experiential world, clearly distin-guished from mere physical things. Each is given as a sensitive living

body belonging to an “I” that senses, thinks, feels, and wills. This “I” faces “me” and my phenomenological world and communicates with “me.” Her investigation proceeds from these data of foreign experience to questions about the nature of the acts in which foreign experience can be grasped: the acts which she designates as empathy. She attempts to grasp its nature by means of lengthy analyses of empathic experiences, such as the experience of another’s pain and of another’s joy. The expe-rience of joy is a favorite example of Stein throughout her work.

Her directing purpose is to investigate philosophically the nature of empathy, but she engages in a preliminary examination of the psycho-logical process of its genesis, comparing her theories with those of Theodor Lipps and Max Scheler. Empathy, she holds, is an act of per-ceiving that is sui generis, an act which is primordial as present experience but non-primordial in content. When the empathizing subject is living in another’s joy, for example, he/she does not feel primordial joy. It does not issue from his/her “I,” nor does it have the character of ever having lived as remembered joy or fancied joy; but in this nonprimordial experience, the “I” is led by the primordial experience of the other subject’s joy. The joy itself cannot be outwardly perceived, but its object, a joyful countenance or other outward sign, is perceived outwardly, and the joy is given “at one” with the object. In a different situation, the “I” may hear of the joyful event before meeting the other, and the “I” can have the primordial act of joy without first grasping the other’s joy.28

The awareness of what empathy is as well as that it is linked by Stein with the understanding of the “I” as person, and the understanding of person is aided by descriptive analyses of empathy. If one follows the line of her reflections and analyses, however, it may be seen that this is not a vicious circle but a phenomenological viewing from all sides that reveals for her the ontological structure of the person.

The awareness of one’s being that is concomitant with the acts of consciousness is the awareness of the self which is simply given as the subject of experience and is brought into relief in contrast with the otherness of the other, when another is given. This “I” is empty in itself and depends for its content on experience of the outer world and of an inner world. Upon reflection it is revealed as the subject of actual qualitative experiences, with experiential content, lived in the present and carried over from the past, experiences which form the unity of the stream of consciousness. This affiliation of all the stream’s experiences with the present, living “pure I” constitutes an inviolable unity. Now other

streams of consciousness are given in experience, and the stream of the “I” faces those of the “you” and the “he” or “she,” each distinguished by virtue of its own experiential content and each affiliated or belonging to an “I.”

Examining the unity that characterizes the stream and the persistence apparent in the duration of feelings, volitions, and conduct, Stein posits one basic experience, which together with its persistent attributes becomes apparent as the identical “conveyer” of them all, their substrate. She calls this substrate the soul (Seele). This substantial unity is “my” soul when the experiences in which it is apparent are “my” experiences or acts in which my “pure I” lives.29

This psychic phenomenon, she adds, is incomplete, for it cannot be considered in isolation from the body: It is also body-consciousness. The body given in consciousness is sensed as “living body” (.Leib) in acts of inner perception and in acts of outer perception. It is outwardly perceived as physical body (Korper) of the outer world. This double givenness is experienced as the same body. The affiliation of the “I” with the perceiving body is inescapable, since the living body is essentially constituted through sensations, and sensations are real constituents of consciousness, belonging to the “I” and received through stimuli from existing things. In addition to having fields of sensation, the living body in contrast to the physical body is characterized by being located at the zero point of orientation of the spatial world, by moving voluntarily, and by having and expressing feelings.

It is obvious that fields of sensation are inseparable from their cor-poreal founding. On the other hand, general feelings, such as feeling vigorous or sluggish, may seem to be capable of being somatic or non-somatic. Moods, for example, are general feelings of a non-somatic nature, but their foundation is in the phenomenon of the reciprocal action of psychic and somatic experiences.

Feelings of both types demand bodily expressions which may be external or internal, or both. It is true that verbal expression and observ-able bodily expression, such as smiling, groaning, and the like, can be controlled; but feeling is still expressed internally in bodily changes, such as those of heart-beat, pulse, or breathlessness, and/or in acts of reflection. Also outward expression may be stimulated. Even so-called “mental feelings,” such as boredom, disgust, keenness of wit, upon analysis can be seen to have some connections of cause/effect with the living body. In all these analyses, Stein is attempting to establish that everything psychic is body-bound consciousness and that the soul together

with the living body forms the substantial unity of the psycho-physical individual.

The living body is also the instrument of the “I’s” will. Experiences of will have an important meaning for the constitution of psycho-physical unity. Both willing and striving make use of psycho-physical causality, but what is truly creative is not a causal, but a motivational, effect. Will may be causally influenced, as for example, when tiredness of body prevents a volition from prevailing, but a victorious will may overcome tiredness. What is truly creative about volition is not a causal effect; the latter is external to the essence of will.30

The above description shows how Stein has given in outline an account of what is meant by the psycho-physical individual. It is revealed as a unified object inseparably joining together the conscious unity of an “I” and a physical body which occurs as a living body, and consciousness occurs as the soul of the unified individual. This unity has been revealed by examining sensations, general feelings and their expression as well as the causal relationship between body and soul and the outer world. Finally, the living body has been considered as the instrument of the “I’s” will.

(b) Knowledge of Other Persons. With a similar type of painstaking analysis, Stein examines step by step the nature of the “I’s” conscious-ness of the foreign individual. In the popular English usage of the term empathy, the focus is usually on the feeling aspect. Also the German word Einfiihlung gives primary philological reference to feeling. In Stein’s theory of empathy, the unity of the “I” becomes clearly evident in the grasp of the other which occurs both cognitively and affectively. Her account shows the impossibility of separating feeling from the total complex of cognitive acts, such as perception, ideation, and insight.

Through “sensual empathy,” the “I” perceives and interprets the other as sensing, living body and empathically projects itself into it. In acquiring objective knowledge of the existing outer world, empathy has an important function. Although the outer world may appear differently to different individuals to some extent because of different sense capac-ities and perspectives, the world appears much the same however and to whomever it appears. If the “I” were imprisoned within the boundaries of its own individuality, it would not get beyond the “world as it appears to me.”31 Further, intersubjective experience is presented as significant in reaching knowledge of the self. Empathy and inner perception of self must work hand in hand in order to “give me myself to myself.”32

At this stage of her investigation, Stein observes intimations of the self that transcend the world of nature. She has shown that the psycho-physical individual as nature is subject to the laws of causality, but they do not account for a wide range of phenomena of consciousness. Consciousness appears not only as a causally-conditioned occurrence but as object-constructing at the same time. Thus it steps out of the order of nature and faces it. Analysis of attitudes, feelings, values, and cognition as well as volition and action reveals the human individual as being that is subject to rational laws, the laws of meaning. In every grasping of an act of feeling, she holds, the human being penetrates into what she calls the realm of Geist, spirit. As physical nature is constituted in perceptual acts, so a new realm is constituted in feeling. This realm is the world of values. Geist is further revealed in the realm of the will, which not only has an object correlate facing the volition but is also creative, releasing action, effecting whatever “man has wrought” in human relations, as well as in the arts, sciences, and all making. All these are correlates of Geist.33

The word Geist has no adequate English equivalent, the nearest being “mind” or “spirit.” Here it will be rendered by “spirit” since it appears to have the advantage in expressing Stein’s comprehensive concept which includes not only intellectual cognition but also feelings, values, and volitions. It is to be understood that “spirit” in this context does not have reference to the moral or the religious. The word geistig is likewise difficult to translate. For consistency, it will be rendered “spiritual,” in the sense of distinction from the psychical and the physical.34

The manner in which Stein constitutes the knowledge of spiritual person (geistige Person) is highly original in that she arrives at ratio-nality by way of analyses of feelings. She does not begin with what she calls “theoretical acts,” such as perception, imagination, ideation, and inference, she says, because in these one may be so absorbed in the object that the “I” is not aware of itself. Instead she concentrates on feeling (for example, the feeling of joy), since in this the “I” is always present to consciousness. But feeling always requires theoretical acts, and involves values, and both of these lead to the rational.

Sentiments of love and hate, gratitude, vengeance, animosity - that is, feelings with other people as their object - are acts revealing spirit, which is characteristic of personal levels. In the act of loving, one expe-riences a grasping or intending of the value of a person. One loves a person for his or her own sake. In a feeling of value one becomes aware of the self as subject and as object, and every feeling has a certain

mood component that causes feeling to be spread throughout the “I” and can fill it completely. Feelings have different depth and reach, dif-ferent intensity and duration, and these are subject to rational laws. The “I” passes from one act to another in the form of motivation - the meaning context that is completely attributable to spirit. Thus the person as spirit is the value-experiencing subject whose experiences interlock into an intelligible, meaningful whole.

Analyses of strivings, volitional decision, and willing follow. Every willing is based on the feeling of “being able.” Every act of feeling as well as every act of willing is based on a theoretical act. The act of reflection in which knowledge comes to givenness can always become a basis for a valuing. Cognitive striving and cognitive willing involve feeling the value of the cognition and joy in the realized act. Person and value-world are found to be completely correlated.

Personal attributes such as goodness, readiness to make sacrifices, the energy which I experience in my activities are conceivable as attributes of a spiritual subject and continue to retain their own nature in the context of the psycho-physical structure. They reveal their special position by standing outside the order of natural causality. Action is experienced as proceeding meaningfully from the total structure of the person. It is spirit, she holds, that is the distinctive characteristic of person and a requisite for empathy, for only the person as spirit can go beyond the self and relate cognitively and affectively to others in the full sense of these relations.35

This early work of Stein builds the framework of the structure of the human person, which she expands, modifies, and enriches in subsequent writings. The detailed consideration of it here is designed to show the ways in which she attempted to implement Husserl’s methodology, viewing each object of investigation from all sides and striving to validate successive findings at each stage of the procedure. Thus she contributes to the realization of an important aim of phenomenology in providing access to universal essence in a context of concrete human experience.

Edith Stein’s next work, Beitrage zur philosophischen Begriindung der Psychologie und der Geisteswissenschaften (Contributions to the Philosophical Foundations of Psychology and the Human Sciences),36 published five years later, in 1922, continues her search for a deeper knowledge of the human person. It was her conviction that phenome-nology was the most appropriate approach to the investigation of the structure of human personality, which would ultimately supply the grounding knowledge for the structure of the human sciences.

(c) Consciousness and Spirituality. Her investigation again takes the form of analysis of the phenomena of consciousness, the objects in their entire fullness and concretion as well as of the consciousness corre-sponding to them: the neomatic levels and gradations and the noetic elements in all their complexity. She examines the experience-units which rise, peak, flow into the past, often emerging again, in the unity of the stream; also the life-feelings (Lebensfuhle), the life-states (Lebenszustandlichkeiten) and life-force (Lebenskraft) of the real “I” which come to givenness. She designates the real “I” and its qualities and conditions as the psychic. Conclusions regarding psychic causality are shown to be only approximate and non-exact, but as having practical value.37

In making the transition from the psychic to the realm of spirit, Stein arrives at a radical distinction between causality and motivation. To appreciate the clarity, completeness, and even originality of her reach for understanding of these and related complex questions, one must follow her meticulous analyses - sometimes a tedious task but worth the effort; for the outcomes are valuable to the reader on many levels, including the personal and the pedagogical. The course of motivation is shown to be a series of acts that move to meaning. The “I,” the center and turning point of all acts, directs its gaze on the lived ensemble of intentional objects in consciousness and grasps their connections, pro-gressing from act to act with a constantly developing continuity of meaning. The subject can bring the act-life under the laws of reason and can regulate the course of the motivation. “Motive” is the meaning content (;Sinngehalt) which involves perception of a thing’s existence and a vague grasp of its whatness as steps in the comprehension of a value which can motivate the taking of an attitude and, possibly, a willing and a doing.38 In all this, the degree of spontaneity is carefully investigated. Stein recognizes the complexity of the influence of the outer and inner situation on the decision, resolution, and execution of the will act, but she holds firmly to the freedom of the person within proper limits. She meets and finds untenable the arguments regarding determination by the strongest motive and also determinism on the basis of the principle of association.39

Finally, her careful distinction between psyche and spirit in the human being should be noted. The psychic life has to do with the soul, with its constant and variable dispositions; this life refers to a subjective consciousness, monadic and closed. Spirit, on the other hand, has to do with objectifiable contents of intentional acts: thoughts, ends, values,

creative acts. This is why their bearer is an individual person with a qualitative point of view, incarnating a unique value. A true science of spirit, she states, should recognize the autonomy and individuality of the person, while recognizing at the same time that every person is subject to general laws of nature and of psychic life. Although the latter are less precise than the former, knowledge of these laws can afford the basis of a limited prevision, the eidetic possibilities, of what can take place, not what must or will take place. Her final view of the human person in this work is that of a totality of qualitative particularity formed from one central core (Kerri), from a single root of formation which is unfolded in soul, body, and spirit.

Stein devotes many pages toward the end of the work to the descrip-tion of psychic and spiritual faculties in the context of her treatment of community and her attempt to distinguish soul from spirit. In regard to the latter, she herself concludes that the boundaries between soul and spirit cannot be firmly drawn and strict separation cannot be made.40 After many years of contact with the thought of Aristotle and Aquinas, she presents a modified view in her long metaphysical work, Endliches und Ewiges Sein (Finite and Eternal Being).41 Following her long treatment of the structure of concrete being in terms of potency and act, essence and existence, substance and accident, matter and form, she returns to the question of What is Menschseinl (What is human being?) She acknowledges the mystery of human nature, since the entire conscious life, upon which she has relied for knowing what it means to be human, is not synonymous with her being. It is only the lighted surface over a dark abyss, which she must seek to fathom.42

She now defines soul in the Aristotelian-Thomistic sense as the substantial form of a living body. There is a plant soul, and animal soul, and the human soul, each differing essentially from the other. As form, the soul is the principle of life and movement and gives essence- determination to the being. A person is neither animal nor angel - but is both in one. The conscious Ichleben gives access to the soul just as sensuous life gives access to the body. When the “I” goes beyond originary experience and makes the self an object, the soul appears to it as thing-like or substantial, having enduring characteristics, having powers or faculties which are capable of and in need of development, and having changing attitudes and activities. Each human being has not only universal essence but also individual essence.43 These are not two separate essences but are a unity in which the essential attributes join together in a determinate structure. In Socrates, for example, his Socrates-

sein is distinguished from his humanity, his Menschsein. Humanity is part of the individual essence of Socrates.44 His individual essence makes the whole essence and every essential trait something unique, so that the friendliness or goodness of Socrates is other than that of other men. Individual essence unfolds in the life of this man; it is not static; it can change. Not all that is grounded in essence follows necessarily; the person has freedom in forming individual essence.45

In this work, Stein retains the two designations soul and spirit, but the distinction does not appear to be a real one. As form of the body, she writes, the soul takes the middle position between spirit and matter. She writes:

Spirit and soul are not to be spoken of as existing side by side. It is the one spiritual soul which has a manifold unfolding of being.... The soul is spirit according to its innermost essence, which underlies the development of all its powers.46

The person, the “I,” she holds, is a three-fold oneness: body-soul-spirit. As spirit, the human person is the bearer of his/her life - holds it in hand, so to speak. The person’s knowing, loving, and serving and the joy in knowing, loving, and serving are the life of spirit, the proper sphere of freedom. And again she affirms that under spirit we understand the conscious, free “I”; free acts are the privileged realm of person. The “I” to which body and soul are proper, the same “I” which encompasses the spirit “I,” is the living-spirit-person, the conscious free “I.”47

From this point on, Finite and Eternal Being moves beyond philos-ophy to theology, treating the threefold unity of body-soul-spirit in man as the image of the Triune God. In a later work also, Welt und Person48 (World and Person), Stein takes the person from the realm of natural reason to the realm of grace.

(d) Woman. In the compilation of Stein’s lectures on woman delivered in German cities in 1930, entitled Die Frau49 (Woman), her philosophy of education appears directly related to her philosophy of person. Education, she states, is the formation of human personality. In each human being there is a unique inner form which all education from outside must respect and aid in its movement toward the mature, fully developed personality. The humanness is the basis of fundamental com-monalities. Education must help all persons to develop their powers of knowing, enjoying, and creative making.

Intellect is the key to the kingdom of the spirit.... The intellect must be pressed into activity. But... the training of the intellect should not be extended at the expense of the schooling of the heart. The mean is the target.50

The disciplines should be taught not in a purely abstract way but should be related to the concrete and personal as far as possible.

Her philosophy of woman likewise grows out of her philosophy of person. She presents the being of woman under three aspects: her humanity, her specific femininity, and her individuality. Her treatment of woman as a member of the human species is traditional, but she adds that within the human species there is a “double species” of man and woman. Differences in gender, rooted as they are in bodily structure, may be the basis of some personality differences, but these differences apply only in general. Some women have characteristics which are considered typically “manly,” and some men have characteristics that are “womanly.” There is no profession that cannot be carried on by women, she maintains, and some women have special aptitude for some professions that have been considered as belonging principally to men, such as that of doctor.51

(e) Individual and Community. Edith Stein presents a valuable treat-ment of the individual and community in the second section of the Beitrage,52 making use of phenomenological method (exclusive of the transcendental reduction) and analyses of the actual experience of com-munity. She distinguishes between society (Gesellschaft) and community (Gemeinschaft). In a society a man regards himself as a personal subject and other men as objects; in a community the subject recognizes others as fellow personal subjects. In most social groups, there are both societal and communal features, but the dominant quality can be discerned. Three components of the experience of actual community life are: the subject of the communal experience, the experience itself, and the living stream which unifies the experience. The experience of the community has its source ultimately in the individual selves who make up the group. They share an intended common goal of activity and a unity of meaning. Thus the community lives and experiences in and through the individual persons who compose it. Personal freedom should be enhanced by the social grouping, which calls for personal participation that is both cognitive and affective. The “I” can enter into a community life with other subjects. The individual subject can thus become a member of a

supra-individual subject, and in the actual life of such a subject- community, an experience-stream is constituted. How this comes about is uncovered by means of descriptive analyses which build upon the structures treated in her previous works.

Her next work53 applies the conclusions of her investigations into community to her political philosophy, considering the state as a com-munity which also involves some societal elements; these, however, should be subordinate to the interpersonal life of members of the com-munity. The state is, by origin, a natural community-society, not one formed by social contract. The state is characterized by sovereignty; however, it should preserve its character of community by limiting civil power to what is necessary for the common good and by promoting the freedom of its citizens. She does not think that there is any one absolutely best form of government; each has to be considered in relation to the particular circumstances. She takes issue with Fichte and Hegel in their exalting of the state and the unfolding of a dialectical process in being that fails to root the ethical order in personally free agents. Her theory of the state reminds one of Maritain’s ideas of the person and the common good54 in its insistence on the requirements of social responsibility and “amity” (to use Maritain’s term) and in her refusal to grant ethical supremacy to the state. Stein appears to develop a theory that is definitely critical of the rising totalitarianism of the time at which she was writing (1925), while repudiating extreme indi-vidualism. It should be noted also that she presents historical evidence that a state need not confine itself to a single folk or race in achieving the unity of community.55 In her open criticism of totalitarian and racist trends she appears to stand out from other German phenomenologists of the time.

2. Theology

(a) Thomasism and Phenomenology. During the period from 1922 to 193156 Stein extended her philosophical horizon far beyond phenome-nology. She translated from English to German Newman’s letters, journals, and The Idea of a University. Her two-volume translation from Latin to German and interpretation of Aquinas's Disputed Questions on Truth57 was a work of rigorous scholarship and philosophical significance. Martin Grabmann58 and James Collins59 commented favorably not only on her rendering of Aquinas’s Latin into a vital, philosophically pertinent German but also on her interpretation of the text. Incidentally, the

Latin-German glossary of terms which it includes is helpful to scholars who come to German phenomenology from medieval philosophy.

A long article on Husserl’s phenomenology and the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas, which she contributed to a supplementary volume of Husserls Jahrbuch in honor of Husserl’s seventieth birthday in 1929,60 gives evidence of the changes in Stein’s philosophizing. In this work she compares the theories of the two philosophers regarding philosophy as science, natural and supernatural reason, essence and existence, and intuition and abstraction of essence. In September 1932, she accepted the invitation to participate in the Journee of the Societe Thomiste in Juvisy on the subject of phenomenology and Thomism. The summation of the conference by Rene Kremer gives prominence to Stein’s explanations and responses.61

In both of the above works Stein presents the parallelism between phenomenology and Thomism in regard to: the end pursued, namely scientific knowledge having objective validity; the intelligibility of being, that is, the affirmation of an essential, intelligible structure, or logos, in all that is; and the power of reason to attain this intelligibility. The matter of objectivity is too complex to be elaborated in the present account. It should be noted, however, that Stein recognizes that the meaning of Husserl’s objectivity (Gegenstandlichkeit) and validity (Gultigkeit) is problematic: Is knowledge for him objective because it is shown to be universally valid for knowers or is it universally valid because it is objective in the sense of being an adequation of the mind and reality, as Aquinas holds? Husserl’s epoche, the bracketing of the question of existence, in the transcendental reduction is an issue. The Scholastic concept of intentionality, which came to Husserl by way of Brentano, was the basis of the famous “Wende zum Objekt” that phe-nomenology heralded in opposition to idealism. But the object for Husserl was always the mental, or intentional object, which might or might not have its foundation in exterior reality. The crux of the problem of Husserl’s objectivity is expressed in Stein’s phrasing of the question, “How is the world constructed for a consciousness which I can explore in immanence?”62

Both philosophers, she emphasizes, search for knowledge of the essences of things, of what things are. Both begin with perception, and both, she believes, proceed in a similar manner: Husserl, by eidetic reduction; Aquinas by abstraction. Stein presents similarities in Husserl’s intuition (Wesensanschauung) and Aquinas’s intellectus (intus legere). She also raises questions. Here awareness of contrasts between Husserl

and Aquinas is evident in other sections of the article. Examples are: the differences in method, that is, emphasis on synthesis versus analysis; on description versus demonstration; “first philosophy” (the ground of principles of science) as theory of knowledge versus “first philosophy” as metaphysics; and the gap between the existence-bracketing phenomenology of Husserl and the existential character of Aquinas’s philosophy. There is, of course, the great difference between the theo-centrism of Aquinas and the position of Husserl that knowledge of God was beyond the limits of phenomenology.

(b) Finite and Eternal Being. The work that represents the maturation of Edith Stein’s thought, the fruition of her confrontation of Husserl’s phenomenology and Thomas’s philosophy was a monumental manuscript of over thirteen hundred pages entitled Endliches und Ewiges Sein (.Finite and Eternal Being).63 It was completed in 1936 and was already set up in type at Breslau when the order against publishing non-Aryan writings was issued by Hitler. Its subtitle, Attempt at an Ascent to the Meaning of Being indicates that the question of being is the focal point and reminds us of Heidegger in the phrase “meaning of being;” but Stein sees the question of the meaning of being to be inextricably linked to the recognition of a First Being. Finite and Eternal Being is a creative work which draws on its sources but presents an original analysis of the metaphysical structure of being, with methodology and content of its own. Early in the work, the existence of the First Being is rationally inferred from the finiteness of the self, the “I.” Thus, after the first chapter, which discusses the nature of philosophy, Chapter II enters upon the “ascent” to the infinite and eternal being by way of analysis of the experience of the “I” in terms of act and potency. Chapters III and IV are an extensive treatment of the structure of concrete being (potency and act, essence and existence, substance and accident, matter and form), and Chapter V, of the transcendental. Chapter VI, the central section, then treats the meaning of being. Chapter VII is a lengthy treatment of what may be the analogy of being, if the expression is taken in an enlarged Augustinian or Bonaventuran sense; and the final chapter is on individuation.

This brief outline of content gives some idea of the direction the work takes in presenting an ontology that leads to a natural theology, and, it should be added, a natural theology which is open to revealed theology. In the Festschrift article Stein had devoted some pages to the question of the difference between philosophizing with pure reason and philosophizing with faith-enlightened reason, but it is in Finite and Eternal Being

that her final conclusions are to be found. Between the two works, she had read Maritain’s De la philosophic Chretienne and had participated in the discussion of the subject of Christian philosophy at Juvisy and in other discussions of the issue, which was very much alive at the time. Stein affirms the formal distinction between belief and knowledge, stating that philosophical science remains in the sphere of human reason; religious belief and theological science rest on divine revela-tion, but she would not erect barriers between faith and reason, philosophy and theology. “Reason,” she says, “would become unreason if it wanted to stick obstinately to what it can discover by its own light and to close its eyes to what a higher light makes visible.”64

Historically, she maintains, philosophy has received many leads from theology; it should be open to theology and can be completed by it, not as philosophy but as theology. In her opinion, the deciding factor as to whether a work is philosophical or theological is the “directing intention.” Her purpose in Finite and Eternal Being is to keep the directing intention philosophical.65 That she feels free to supplement the truths of reason with the truths of faith is evident, particularly in the section which considers man as the image of the Trinity. It is obvious that she considers some sort of synthesis of faith and reason desirable for the believer, but she insists that philosophy calls for completion by theology without becoming theology. The exposition of her philosophy given by her will, of course, be limited to her philosophy.

3. Metaphysics

(a) Being. It seems likely that when Edith Stein conceived the idea of Finite and Eternal Being, she may have had in mind the words of Pere Ren6 Kremer which she heard at the Journee of the Societe Thomiste at Juvisy: “The question of being,” he noted, “can be resolved only by a complete system embracing finite being and infinite being.”66 He was referring in this context to the system of Aquinas. Stein may have taken his statement as indicating a desirable structure for her “ascent to the meaning of being.” Undoubtedly, she determined to make the attempt to transpose traditional concepts into a contemporary key by making use of the linguistic and methodological resources of phenomenology. In locating the problem of the meaning of being primarily in the recog-nition of First Being, she is faced with the problem of coming to the knowledge of First Being early in her work. Since, to her mind, the existence of God is not intuited in privileged experience nor is it

rationally inferred in a formal demonstration, she initiates a train of thought which avoids the strict use of these ways and yet does not rule out completely the insights of either. As in her earlier works, the starting point of her search is the indubitable fact of one’s own being, most intimately and inescapably known. As in her earlier works, this aware-ness leads her to the awareness of the “I” as subsistent being, distinguishable from all experience as that to which every experience belongs, the “pure I,” which is empty in itself and is dependent for its content on an outer world and an inner world.67 Her procedure is first to establish, by way of phenomenological description, the finitude of man’s being; then to show that finite being demands eternal being as its ultimate ground. The being of the “I,” under her reflective gaze, is first revealed in the finitude of temporality. Even as she contemplates it, its present-actual being has passed away and given place to the being of another “now.” It cannot be separated from time: it is a “now” between a “no longer” and a “not yet.” It has a double face: that of being and non- being.68

Before she completes her analysis of this temporality, her thought rushes forward precipitously to the idea of pure being which has in it nothing of non-being, which is not temporal, but eternal.69 Although it is only the ideas of eternal and temporal, immutable and mutable being that force themselves upon the mind and provide a legitimate starting point, she holds that the analogy of being is visible even at this point. Our actual being is only for an instant; it is not “full being” (voiles Sein), which is the fullness of being at every instant. It is an image (Abbild) whose being bears a likeness to the original (Urbild) but much more unlikeness. The question arises whether this sudden presence to consciousness of eternal being, the plenitude of being, is philosophi-cally premature and dependent upon faith or whether it is an instance of what Karl Rahner calls the pre-apprehension (Vorgriff), by way of excessus, of universal esse and the simultaneous affirmation of the exis-tence of Absolute Being.70 The fact that she is “philosophizing in faith” cannot be summarily dismissed. As Stein herself says in another section of the work, the believer easily leaps over the abyss between finite and eternal being; the unbeliever shrinks back again and again.71

(b) Act and Potency. To establish her pre-apprehension on firmer ground, Stein proceeds to extend analyses which make use of the traditional concepts of act and potency, clarified and brought to givenness in personal, conscious experience. In her analysis, the finitude of the being

of the “I” is revealed in the awareness of the continuous passage from potency to act, and the concrete awareness of becoming is uncovered in the analysis of “experience-units” (Erlebniseinheiten). Husserl’s concept of actuality and inactuality, applied to the temporality of con-sciousness72 and Hedwig Conrad-Martius’s concept of the fleeting actuality of the “ontic present”73 are threaded through the doctrine of potency and act in an original way. With Husserl she stresses the inner subjective flux of consciousness and temporality as an essential property of consciousness. In Stein’s development, the consciousness of time is never removed from the ambient of the real world.

The unity of the unceasing flux of consciousness is constituted by the “pure I,” which alone remains constant. It belongs to the essence of the intentional experiences of this stream to be situated in the con-tinuous time-horizon of past, present, and future, a horizon in which actuality belongs to the “fully-living” present; potentiality to the past and the future. The present, the “now,” the indivisible instant, is the contact point with existence. The Ichleben appears as a constant going-out-of- the-past-living-into-the-future, in which the potential becomes actual and the actual sinks back into potentiality. This continually fleeting point of actuality reveals to us the opposition between actuality and potentiality in our being, but even this point is not pure actuality. In the present-actual instant, our being is both actual and potential.74

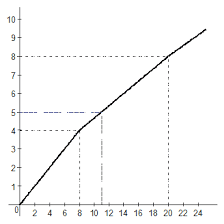

Exploring further this composition of act and potency in our being, Stein turns to the experience-units of consciousness and their charac-teristic of duration.75 The experience of joy, for example, has duration which encompasses a waxing and waning. The experience stream is a unity, not of a chain made of links, but of a stream flowing in waves that rise from the lower level of that which is not yet “full-being” to the crest of the height of being (Seinshohe) and of aliveness (Lebendigkeit) and fall to the level of the being of retention, that which is lived and gone (Gelebtin-Vergangen). The experience of joy over good news is selected for detailed analysis, an experience which is conditioned both by the object, the content of the news, and the subject, the “pure I,” which understands the news and recognizes its joyfulness. The “I” can anticipate future joy and can relive the past. Repetition of the expe-rience is accompanied by the consciousness that it is repetition and that it is the same “I” that experiences it. The “I” can look back over the flowing sweep of its earlier life. But there are gaps in memory (occa-sioned by sleep, lapses of consciousness, lapses of memory, and the like), and ultimately the mind is halted before the blank of its beginning. Did

the “I” have a beginning of its being? What of its end? Did it come out of nothing? Faced with the chasms of its past and the mystery of its whence and whither, Stein concludes that the “I” could not be the source of its own life; that it could not possibly call itself into being nor sustain itself in being. Its being must be a received being; it must be placed in being and sustained in being from instant to instant. Experience-units require the “I” for their being; their being is only a coming to be (Werden) and a passing away (Vergehen), with an instantaneous height of being (Seinshohe). The “I” appears nearer to being; yet its being has a constantly changing content, and it knows itself dependent not only in regard to its content, but also in regard to its very being. She calls it a “nothinged being.”76

The “I,” frightened before nothingness, longs not only for the continuation of its being but also for the full possession of being, for being that can enclose its total content in a changeless present. It expe-riences in itself varying degrees of actuality, grades of nearness to the fullness of being. Proceeding in thought to the upper limit by canceling out all deficiencies, the “I” can attain the awareness of the all-encom-passing and highest degree of being, Pure Act, of which it is only a weak image.77

(c) Eternal Being. In subsequent analyses, the Angst of the “I,” as it comes face to face with its own non-being, is countered by the experi-ence that “I am,” and “I am sustained in being from moment to moment,” and “in my fleeting being I hold an enduring being.” “Here in my being I encounter another, not mine, which is the support and ground of my support-less being.”78 Could man’s fleeting being have its final ground in another finite being? It could not, she replies, since everything temporal and finite is, as such, fleeting and ultimately requires an eternal support. The ground of contingent being cannot be received being, but must be being a se (aus sich selbst), being that cannot be, but is necessarily, she concludes.

Eternal being is thus grasped at this point of her analyses as First Being, the Urgrund of the finite being of the “I”; Pure Act, having no potentiality; immutable (wandellos) being; the full possession of being (Vollbesitz des Seins)\ all-encompassing (allumspannendes) and highest encompassing (hochstgespanntes) being; being a se\ necessary being.79

In the section of the book which deals with the analogy of being,80 Stein says that an infinite difference separates the human “I” from any other which lies within the range of our experience, because it is person.

From human being we come to a grasp of the divine esse if we take away everything of non-being that was discovered in the finite “I.” God’s “I” is eternally living presence, without beginning and without end, without any lacunae or obscurity. His Ichleben is fullness of being, in self and of self; there are no changing contents, no rising or falling of experiences, no passing from potentiality to actuality. The entire fullness of being is eternal-present. Thus God’s “I am” (sum) says: I love, I know, I will, not as one-after-another or side-by-side acts, but fully in the unity of one divine actuality, in which all meanings of act coincide. He is his being (Sein) and essence (Wesen). He is fullness of being in every sense of the word but especially fullness of being-person.81

The question may be raised why Edith Stein did not select for the title of her book the term zeitlich (temporal) to paralle

2021-07-07

2021-07-07 74

74