- Outer history.

- Dialectal classification.

- Written records.

- OE phonetics: a) word stress; b) vowels; c) consonants.

1. The history of the English language begins in the 5th century when the British Isles were invaded by the Germanic tribes. The invasion was preceded by a certain pre-history of the British.

Britain first was inhabited by cave men, who have left no history after themselves. Later there appeared Iberians, or Iverians, who came from the east and resembled the Basques. Supposition is made even that the Iberians take their origin from some Mongolian tribes who migrated westward in the search of a convenient shelter and who also wanted to inhabit the British Isles. The Iberians were short and dark, harsh-featured and long-headed, they worshipped the powers of Nature, had mysterious and cruel customs (rites) of human sacrifice and held beliefs in totems and ancestor-worship.

Their followers were the Celts, who, being stronger and far more civilized, totally subdued the survivors of the Iberians, enslaved men and married women. The religion to come was that of the Druids. The Celts are described as tall, blue-eyed and fair-haired people who were stronger than the diminutive Iberians. A theory has been proved that when being continent inhabitants the Celts were invaded by the Greeks which resulted in the formation of a Greek type of life. They had weapons, war-chariots. Gradually they spread to Scotland and Ireland and the Isle of Man. Their languages are represented in modern times by Irish, Scottish, Gaelish and Manx. Anyway, later the Celtic tribes were driven westwards by the Germanic invaders, and their modern representatives are Welsh, Cornish and Breton. It was probably the mutual influence of the Iberians and the Celts that prompted the appearance of all the mysteries of dwarfs, goblins, elves and earth-gnomes.

The Romans invaded Britannia in 55-54 BC. The Roman occupation left little trace in England’s history. Julius Caesar made two raids on Britain. He was attracted by the richness of the Isles and his reasons were the economic ones – to obtain tin, pearls and corn. He didn’t subjugate Britain politically as the Romans never created any kind of centralized government in Britain, but made it a province of the Roman Empire with the latter’s growing economic penetration. After the departure of the last Romans the hostilities among the native tribes renewed. To normalize the situation the local chiefs turned for help to the influential Germanic leaders, thus giving a start to the new invasion which gave rise to creating a new powerful nation – the British.

The Germanic tribes, the Teutons, or the Barbarians (Saxons, Angles, Frisians and Jutes) were warriors and sailors. They used to wander to other lands. M.I. Ebbutt in his “Hero myths and legends of the British Isles” writes that physical cowardice was for the Germanic tribesmen “the unforgivable sin, next to treachery to his chief. A quiet death-bed was the worst end to a man’s life, in the Anglo-Saxon creed: it was a “cow’s death”, to be avoided by everything in one’s power, the only worthy finish to a warrior’s life being a death in fight. Perhaps, there was little of spiritual insight in the minds of these Angles and Saxons, little love of beauty; … but they had a loyalty, un uprightness, a brave disregard of death in the cause of duty, which we can still recognize in modern Englishmen”.

The Germanic tribes were of a much lower civilization than the Romans. They were occupied in agriculture, so they took possession of almost all the fertile land and drove the population to the mountainous regions of Scotland, Cornwall and Wales, the remaining representatives were enslaved. Due to very little contact with the invaders the Celtic tongue underwent so few changes.

Nowadays the remaining Celtic languages may completely disappear like Cornish which became extinct in the 18th, or Manx which disappeared after the Second World War. The English speaking population nowadays evidently prevails which is, no doubt, connected with the growing popularity of the tongue. Most of the people speaking their native Scottish Gaelic (which is spoken only in the Highlands by about 75,000 people) or Irish (spoken by half a million people) are bilingual. The nationalist movements of the recent years helped to stop the decline for a period of time but no one is sure how long the period will be.

At the end of the 8th century the Scandinavian Vikings started their devastating raids on the British Isles. The early Viking raids were carried out by Norwegians. In the course of the 9th century the Danes joined in, beginning with a series of attacks on the east coast of England in 835. They were great sailors and brave warriors, they attacked France and Ireland; they discovered and populated Iceland and Greenland; they were the discoverers of America. With the Danes the first historical Viking figures of the invasions come to the fore with the sons of Ragnar Lothbrók who were responsible for the razing of Sheppey in Kent to the ground. By the mid 9th century they had gained a firm foothold on Mercia, Northumbria, Kent and East Anglia and destroyed their dynasties. The resistance to the Danes in the beginning was disorganised and, given the ease of the conquest, they decided to settle permanently in England. This was the first step in the establishment of the so-called Danelaw which was the area in eastern and north-eastern England of the time which was under Danish rule. The Danes were never to leave England entirely. Military incursions into England which were started from Denmark were to stop but those Danes who remained in England were finally assimilated into the English population.

Only Wessex survived, and its leaders became the leaders of the emerging nation.

In 871 king Alfred of Wessex, later named Alfred the Great, came to the throne. It was he who headed the military resistance to the Danes. He was born in Wantage in 849 and by 871 had begun to engage himself in the war against the Danes. For fifteen years (871-886) Alfred waged war against the intruders and succeeded in maintaining Wessex free from Viking influence. He successfully fought with the Danes who by that time had conquered most of Eastern England and were moving southwards towards Wessex. Alfred managed to stop the Danes temporarily and in 878 a treaty with the Danish king was signed according to which England was divided into two parts, Wessex remaining under British control and the rest of the country passed to the hands of the Danish kings. This territory is known in history as Danelaw (Danelagh) and it existed till the 20-s of the 11th century.

The ups and downs of the military struggle with the Danes are described in detail in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, particularly in the section known as the Parker Manuscript, named after a bishop in whose possession the manuscript was for some time.

In the years 886 to 892 Alfred was able to devote his energies to non-military matters, chiefly to educational reform and cultural matters in general, such as the translation of religious works.

In 892 the Danes took on Alfred once more (after several decades of plundering in northern France). The latter, however, succeeded in defending Wessex and English Mercia and in 896 the Danes (consisting of both the Norman and the East Anglia Danes) reconciled themselves to being confined to the Danelaw. Some of them returned to France and others settled down eventually. Three years later, in 899, Alfred, the greatest of Anglo-Saxon kings, died.

Alfred was a highly progressive ruler ever known in history. It was due to him that part of the state budget was spent on establishing schools for the sons of the nobility. He brought in foreign scholars and craftsmen, built monasteries and convents, introduced new laws and enforced them. He translated many books into Anglo-Saxon and ordered to compile the first history book, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was continued after his death. Being a peaceful ruler King Alfred never really desired to rule but live worthily and remain in the minds of his followers after his death.

However, after the death of Alfred the Great in 901 the supremacy of Wessex began to decline, mutual attacks were renewed and the English king Ethelred the Unready (Этельред Неразумный) escaped to France. For a time, from 1017 till 1042, the throne was occupied by Canute, the Danish king Sweyn’s son. After Canute’s death England became independent again.

A most important role in the history of the English language was played by the introduction of Christianity. The first attempt to introduce the Roman Christian religion to Anglo-Saxon Britain was made in the 6th c. during the supremacy of Kent. In 597 St. Augustine’s mission was organized by Pope Gregory the Great. A group of missionaries from Rome landed on the shore of Kent. From Canterbury which became their center the new faith expanded to all the regions of the country in less than a century.

Picture 6.

The introduction of Christianity was the reason of the quick growth of culture and learning. Monasteries with schools attached were built all over the country. Latin became the language of religion and teaching. In the best English monasteries a high standard of learning was reached.

2. The dialect areas of England can be traced back quite clearly to the Germanic tribes which came and settled in Britain from the middle of the 5th century onwards. There were basically three tribal groups among the earlier settlers in England: the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes. The Angles came from the area of Angeln (roughly the Schleswig-Holstein of today), the Saxons from the area of east and central Lower Saxony and the Jutes from the Jutland peninsula which forms west Denmark today.

The four principal Germanic tribes, having invaded Britain, established their separate kingdoms, the principal among them being:

· Northumbria, Mercia and East Anglia in the central eastern part of the country were formed by the Angles;

· Wessex, Sussex and Essex to the south of the river Thames were formed by the Saxons;

· Kent, formed by the Jutes.

Middle English dialects.

Source: www.uni-due.de

The Frisians didn’t form a separate kingdom but intermarried with the population belonging to different tribes.

The Frisians didn’t form a separate kingdom but intermarried with the population belonging to different tribes.

Of these three groups the most important are the Saxons as they established themselves as the politically dominant force in the Old English period. A number of factors contributed to this not least the strong position of the West Saxon kings, chief among these being Alfred (late 9th century).

Gradually Wessex, Mercia and Northumbria began to dominate over the other kingdoms thus stepping towards unification of England. Another important event contributing to the unity was the introduction of Christianity in AD 597 after which it became a general tendency that the dominating kingdom was the center of religious life in the country.

The OE dialects are generally named after the names of the kingdoms on the territory of which the given dialect was spoken – the Northumbrian dialect, the Mercian dialect, the Wessex dialect, etc. The differences between those dialects were at first slight, and records of the 8th and 9th centuries reveal that there emerged an independent language collectively known as Englisc. The separation of the country from the continent gave rise to the appearance of the distinctive features of the future English language which already then was distinguished from its parent Germanic language.

As the majority of OE texts are in the Wessex dialect it is considered to be the most important among the others. The West Saxon dialect was also strongest in the scriptorias (i.e. those places where manuscripts were copied and/or written originally) so that for written communication West Saxon was the natural choice. First of all one should note that by England that part of mainland Britain is meant which does not include Scotland, Wales and Cornwall. These three areas were Celtic from the time of the arrival of the Celts some number of centuries BC and remained so well into the Middle English period.

A variety of documents have nonetheless been handed down in the language of the remaining areas. Notably from Northumbria a number of documents are extant which offer us a fairly clear picture of this dialect area. At this point one should also note that the central and northern part of England is linguistically fairly homogeneous in the Old English period and is termed Anglia. To differentiate sections within this area one speaks of Mercia which is the central region and Northumbria which is the northern part (i.e. north of the river Humber).

A few documents are available to us in the dialect of Kent (notably a set of sermons). This offers us a brief glimpse at the characteristics of this dialect which in the Middle English period was of considerable significance. Notable in Kentish is the fact that Old English [y:] was pronounced [e:] thus giving us words like evil in Modern English where one would expect something like ivil.

3. The earliest written records of English are those made on wood, stone or metal in a special alphabet known as the runic alphabet, or the Runes. The number of the runes in England was about 24-33 letters. The origin of this alphabet is not known to modern scholars. The word “rune” meant “mystery”, and those letters were originally considered to be magic signs known to very few people, mainly monks, and not understood by the vast majority of illiterate population. The only runic inscriptions found in Europe are an inscription on a box known as the “Franks’ Casket” found in France, the other is a short text on a stone cross known as the “Ruthwell Cross” in the south-west of Scotland. Both records are in the Northumbrian dialect.

The casket is a small whale bone box with inscriptions on its four sides telling how the box was made (the other sources, though, say it tells about legendary beings). The Ruthwell Cross is a 15 feet tall stone cross inscribed and ornamented on all sides. The principal inscription has been reconstructed into a passage from a religious poem. It was found in Scotland.

In the 7th c., when the Christian faith was introduced, there came Latin-speaking monks, who brought with them their own Latin alphabet which day by day ousted the runic alphabet. Anyway, the new alphabet could not denote all the sounds existing in the English language, e.g. (w), (θ), that was why some runes were preserved (w, Þ, ð), in other cases some Latin letters were slightly altered - to denote the sounds (ð), (θ) together with the rune.

This new alphabet was known as “insular writing”, i.e. alphabet typical for the Isles. The spelling of the writings was mainly phonetic and reasonably consistent.

OE records are usually classified either in accordance with the alphabet used or in accordance with the dialect of the tribe who wrote the record.

According to the alphabet (runic or insular) the records are divided into two groups, the first being represented by two inscriptions, the Franks’ Casket and the Ruthwell Cross. According to the other principle, more groups are distinguished: Northumbrian (Franks’ Casket, Ruthwell Cross and Caedmon’s hymns), Mercian (translation of the Psalter), Kentish (psalms), West Saxon (the Anglo-Saxon chronicle, the translation of a philosophical treatise Cura Pastoralis, King Alfred’s Orosius – a book on history).

There were also many translations from other languages, e.g. Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English people (731 AD), Pope Gregory the First’s The Pastoral Care; the translations were made by Alfred the Great. Bede the Venerable is said to be a most learned monk of the time, he wrote on language, science and chronology and composed many commentaries to the Old and New Testament.

Among the authors of the OE period are the two great names, those of Caedmon and Cynewulf. Caedmon is known for the poetical version of the Bible; Cynewulf is the author of a number of poems on religious subjects.

There is another brilliant example of the OE literature the author of which is unknown, that is the epic poem Beowulf. The action in the poem takes place in various places in Scandinavia and has nothing to do with England and her people. The principal events are the fight of young Beowulf with a sea monster, Beowulf’s victory and his later life as the successor of his uncle who had once been the king of the country. The epic ends when Beowulf kills the monster’s mother and, poisoned by her, dies.

Old English poetry is distinguished for the peculiarities in its style. The same thought might be repeated several times but in different ways. The language of the OE poetry is rich in synonyms, e.g. the notions of warrior, sea and ship had more than 20 synonyms. One more characteristic feature is the wide use of epithets. Some words used in poetry were not characteristic of prose, those were poetic archaisms.

4. In OE a syllable was made prominent by an increase in the force of articulation; in other words, a dynamic or a force stress was employed. In disyllabic and polysyllabic words the accent fell on the root morpheme or on the first syllable. Word stress was fixed; it remained on the same syllable in different grammatical forms and in word-building, e.g.

hlāford (Nominative case) – hlāforde (Dative case).

In polysyllabic words there might be two stresses, chief and secondary, the first stress being fixed on the root morpheme. In words with prefixes the position of the stress varied: verb prefixes were unaccented, while in nouns and adjectives the stress was commonly thrown on the prefix.

The Old English system of sounds included the following:

- vowels and diphthongs

a ā æ ǽ e ē i ī o

[a] [a:] [æ] [æ:] [e] [e:] [i] [i:] [o]

ō u ū y ŷ ea eo ie

[o:] [u] [u:] [y] [y:] [æa] [eo, eö] [i]

-consonants

b c cg d ð f ff g h l m

[b] [k,t∫] [dg] [d] [θ, ð] [f, v] [f:] [g, j, γ, dg] [h, χ] [l] [m]

n p r s ss sc t þ þþ p/w x

[n] [p] [r] [s, z] [s:] [∫, sk] [t] [θ, ð] [θ:] [w] [ks]

There were some abbreviations used in Old English manuscripts:

¯ þ ğ þoň דּ

-m or –n, þæt ge-/ʒe- þonne and/ond

eg. sūne=sumne

Note that:

a) c = [t∫] usually before or after a front vowel, [k] elsewhere;

b) ð/þ = [θ] initially, finally or next to voiceless consonants, [ð] elsewhere;

c) f was pronounced [f] initially, finally or next to voiceless consonants, [v] elsewhere;

d) ʒ was pronounced [γ] between vowels and voiced consonants, [j] usually before or after a front vowel, [dʒ] after n, [ʒ] elsewhere;

e) h was pronounced [x] after back vowels, [h] elsewhere;

f) n was pronounced [η] before g and k;

g) s was pronounced [s] initially, finally or next to voiceless consonants, [z] elsewhere;

h) the letters j and v were rarely used and were nothing more than variants of I and u respectively;

i) the letter k was used rarely and represented [k].

As mentioned above, the spelling in Old English was mainly phonemic, e.g.

fīf [fi:f] ‘five’ frefer [frevər] ‘consolation’ hūs [hu:s]‘house’ rīsan [ri:zan] ‘rise’ þurh [θurx] ‘through’ ōðer [o:ðər] ‘other’ gān [gɑ:n] ‘go’ gift [jift] ‘dowry’ fugol [fuɣol] ‘bird’ cēne [ke:nə] ‘sharp’, cyrice [tʃyritʃə] ‘church’.

OE vowels were classified into stressed and unstressed, long and short, monophthongs and diphthongs.

The quantity and quality of the vowel in OE depended upon its position in the word. Under stress any vowel could be found but in an unstressed position there could be only short vowels [a], [e], [i], [o], [u].

The length of the stressed vowels was phonemic, which means that there were pairs of words differing only in the length of the vowel:

metan (to measure) – mētan (to meet)

pin (pin) – pīn (pain)

ʒod (god) – ʒōd (good)

Long and short vowels were paralleled. There were four diphthongs in later Old English: ea, æa [æa, æ:a] and eo, ēo [eə, e:ə] which were sensitive to the consonants which followed them. In the diphthongs the first element was always stronger than the second. Examples for the contrast in length are listed in the columns below.

| System of long vowels System of short vowels |

| [i:], [y:], [u:] [i], [y], [u] |

| [e:], [o:] [e], [o] |

| [æ:] [æ] |

| [a:] [a] |

| i: - i īs 'ice', is 'is' |

| y: - y bŷre 'cowshed', byre 'child |

| e: - e bēn 'plea', ben(n) 'wound' |

| æ: - æ dǽl 'part', dæl 'valley' |

| a: - a hām 'home', ham(m) 'ham' |

| o: - o hōf 'hoof', hof 'enclosure' |

| u: - u hūs 'house', sum 'some' |

Being of Common Germanic origin, the English vowels changed at every period of history. The vowel change begins with the growing variation in pronunciation and appearance of allophones, or variants of the sound. When some of the allophones begin to prevail, the replacement takes place. During OE assimilative (those explained by the phonetic position of the sound in the word) and independent (those that took place irrespective of the sound’s position in the word) changes took place in the language. The most important assimilative changes were breaking and palatal mutation.

Breaking consisted in the change of two vowels – (æ) and (e) under the influence of the following consonants (r), (l), (h). The process resulted in the appearance of the diphthong (ea) instead of the above mentioned monophthongs.

Mutation is a change of one vowel to another through the influence of a vowel in the succeeding syllable. Palatal mutation is the fronting and rising of vowels through the influence of (i) and (j) in the following syllable.

The OE consonant system consisted of 14 consonant phonemes denoted by the letters p, b, m, f, t, d, s, r, l, þ, ð, c, ʒ, h. There were no such sounds as [t∫, dʒ, ∫]. The quality of certain consonants depended upon their position in the word:

a) the phonemes denoted by f, θ or s were voiced when between vowels and voiceless otherwise ([f] – [v]: hlaf bread – hlaford bread-keeper, lord; [f]: līf live, feld field; [v]: wefan weave, wulfas wolves; [θ]: þusend thousand, bliþs bliss; [ð]: aðas oaths, muðas mouths; [s]: sunu son, nest nest; [z] wesan to be, clænsian to cleanse); this alternation can be seen to this day and is responsible for present-day alternations like wife-wives;

b) the phoneme denoted by the letter c gave two variants: [k’] when before i and [k] in all the other cases (cild child – can can, scip ship – climban to climb);

c) letter g also gave two phonemic variants: [ʒ] at the beginning of the word before back vowels or consonants or in the middle of the word after n and [j] or [γ] in other positions (ʒod good, ʒretan to greet, ʒanʒan to go; daʒas days, ʒear year).

The system of consonants as well as vowels underwent certain changes which are best reflected and explained in Grimm’s law and Verner’s law.

Additional reading…

The Roman Invasion.

One of the earliest westward migrations was made by a people whose descendants now live in Cornwall, the highlands of Scotland, Ireland, Wales and Brittany: the Celts. These Gaelic-speaking tribes were natives of the British Isles long before the English. Today, the people of Wales prefer to call themselves cymry, or "fellow-countrymen", a reminder that they -together with the Irish, Scots and Cornish - are the true Britons.

The Celtic Britons had the misfortune to inhabit an island that was highly desirable both for its agriculture and for its minerals. The early history of Britain is the story of successive invasions. One of the most famous was the landing of Julius Caesar and his legions in 55 BC. Written history in Britain starts with that event. The Romans were never really interested in Britain and did not take the trouble to conquer it entirely. Thus in the West Cornwall and Wales remained firmly Celtic, as did the North and all of Scotland. It is true that Hadrian’s Wall (built c. 122-130) is quite far north (near the present-day border with Scotland but Roman settlements in the north of England are rare. The two main Roman groups are the Catuvellauni north of the Thames and the Atrebates south of this river. The Roman groupings in Britain tended to distance themselves from Rome and to some extent enter alliances with local (Celtic) leaders. The Celtic areas provided welcome refuge for Roman leaders who were in trouble with fellow Romans in Britain. Things came to a head in the early part of the first century AD and a Roman invasion of Britain in 43-47 AD under the emperor Claudius was supposed to put an end to this strife. Military engagements continued throughout the first century and into the second with an approximate status quo being achieved with the building of Hadrian’s Wall. Wales remained a stronghold of Celtic resistance to Roman rule and no attempt to subdue the Welsh was successful.

As might be expected Romanisation was greatest in Britain in the towns and among the ruling classes. The countryside remained linguistically Celtic, despite the presence of Roman villas. Equally no influence of the substrate Celtic language is to be found in the Latin written in Britain at this time.

The civilizing energies of the Anglo-Saxons received an enormous boost when Christianity brought its huge Latin vocabulary to England in the year AD 597. The remarkable impact of Christianity is reported by the Venerable Bede in a story which says as much about the collision of Old English and Latin as it does about the spread of God's word. According to the famous tradition, the mission of St Augustine was inspired by the man who was later to become Pope Gregory the Great. He sent Augustine and a party of about fifty monks to what must have seemed like the end of the earth. Augustine and his monks landed in Kent, a small kingdom which, happily for them, already had a small Christian community.

The conversion of England to Christianity was a gradual process, but a peaceful one. No one was martyred. With the establishment of Christianity came the building of churches and monasteries, the corner-stones of Anglo-Saxon culture, providing education in a wide range of subjects. The new monasteries also encouraged writing in the vernacular, and all the plastic arts. Astonishing work in stone and glass, rich embroidery, magnificent illuminated manuscripts, were all fostered by the monks, as was church music and architecture.

The importance of this cultural revolution in the story of the English language is not merely that it strengthened and enriched Old English with new words, more than 400 of which survive to this day, but also that it gave English the capacity to express abstract thought. Before the coming of St Augustine, it was easy to express the common experience of life - sun and moon, hand and heart, sea and land, heat and cold - in Old English, but much harder to express more subtle ideas without resort to rather elaborate, German-style portmanteaux like “frumweorc” (“fruma” – “beginning” and “zveorc” – “work” = “creation”). Now, there were Greek and Latin words like angel, disciple, litany, martyr, mass, relic, shrift, shrine and psalm ready to perform quite sophisticated functions. The conversion of England changed the language in three obvious ways: 1) it gave us a large church vocabulary; 2) it introduced words and ideas ultimately from as far away as India and China; 3) and it stimulated the Anglo-Saxons to apply existing words to new concepts.

Church words came from Latin, Greek and Hebrew. Disciple, shrine, preost, biscop, notme and munuc (monk) all have Latin origins. Apostle, pope and psalter are borrowed, via the Scriptures, from Greek. Sabbath comes from Hebrew. Angelas (messenger) and diabolos (slanderer) were transformed into angel and devil, central figures in the Madame Tussaud's of early Christianity. Easter is a curiosity: the word preserves the name of Eostre, the pagan goddess of dawn. To understand the speed and completeness with which the language of the Bible was absorbed into Old English, we have only to think of the way in which our own contemporary vocabulary has become permeated by the language of psychology" and psychoanalysis with words like ego, id, angst and subconscious.

The oriental origins of the Christian faith introduced words from the Bible - camel, lion, cedar, myrrh - which must have seemed as exotic and strange to a seventh-century Englishman as, say, recent borrowings from Japanese culture like kamikaze andju-jitsu did at first. Also from the East came exotic words like orange and pepper, the names India and Saracen, and phoenix, the legendary bird. Oyster and mussel are both Mediterranean borrowings, while ginger comes ultimately from Sanskrit.

Perhaps most interesting of all is the way Old English reinvented and rejuvenated itself in the face of this Latin cornucopia by giving old words new meanings. God, heaven and hell are all Old English words which, with the arrival of Christianity, became charged with a deeper significance. The Latin spiritus sanctus, or Holy Spirit, became translated as Halig Gast (Holy Ghost); feond (fiend) was used as a synonym for Devil, and Judgement Day became, in Old English, Doomsday. The Latin evangelium (good news) became the English god-spell which gives us gospel. To this day, the power of the English language to express the same thought or object in either an early vernacular or a more elaborate Latinate style is one of its most remarkable characteristics, and one which enables it to have a unique subtlety and flexibility of meaning.

By the end of the eighth century, the impact of Christianity on Anglo-Saxon England had produced a culture unrivalled in Europe. The illuminated manuscripts of the famous monastery at Lindisfarne, on Holy Island off the Northumbrian coast, show how words and pictures had both achieved a kind of perfection. But in the eighth and ninth centuries this culture faced another threat from what was to become the second great influence on the making of English - the sea-warriors from the North.

Source: www.uni-essen.de

The Germanic settlement of Britain.

The withdrawal of the Romans from England in the early 5th century left a political vacuum. The Celts of the south were attacked by tribes from the north and in their desperation sought help from abroad. The Ecclesiastical History of the English People written by a monk called the Venerable Bede around 730 in the monastery of Jarrow in Co. Durham (i.e. on the north east coast of England) describes the early days of English history. According to this work — written in Latin — the Celts first appealed to the Romans but the help forthcoming was slight and so they turned to the Germanic tribes of the North Sea coast. The date which Bede gives for the first

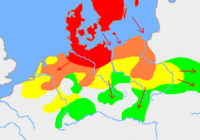

Picture 7. The expansion of the Germanic tribes 750 BC – AD 1 (after the Penguin Atlas of World History 1988): Settlements before 750BC New settlements until 500BC New settlements until 250BC New settlements until AD 1

arrivals is 449. This can be assumed to be fairly correct. The invaders consisted of members of various Germanic tribes, chiefly Angles from the historical area of Angeln in north east Schleswig Holstein. It was this tribe which gave England its name, i.e. Englaland, the land of the Angles (Engle, a mutated form from earlier *Angli, note that the superscript asterisk denotes a reconstructed form, i.e. one that is not attested). Other tribes represented in these early invasions were Jutes from the Jutland peninsula (present-day mainland Denmark), Saxons from the area nowadays known as Niedersachsen ('Lower Saxony’, but which is historically the original Saxony), the Frisians from the North Sea coast islands stretching from the present-day north west coast of Schleswig-Holstein down to north Holland. These are nowadays split up into North, East and West Frisian islands, of which only the North and the West group still have a variety of language which is definitely Frisian (as opposed to Low German or Dutch).

The Germanic areas which became established in the period following the initial settlements consisted of the following seven ‘kingdoms': Kent, Essex, Sussex, Wessex, East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria. These are known as the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. Political power was initially concentrated in the sixth century in Kent but this passed to Northumbria in the seventh and eighth centuries. After this a shift to the south began, first to Mercia in the ninth century and later on to West Saxony in the tenth and eleventh centuries.

In the beginning of the Germanic period, Kent was the centre of political and cultural influence in England. This situation lasted for about 150 years with a Kentish king (Ethelbert) ruling over all of England south of the Humber at one stage. In the seventh and eighth centuries matters changed and at least cultural influence shifted to the north of England. The main reason for this was the establishment of centres of learning in northern England, notably on the island of Lindisfarne (noted for the Old English version of the gospels), at Wearmouth and at Jarrow where the Venerable Bede lived and worked. In the eighth and early ninth centuries political influence moved southwards and lay in the hands of the Mercians until in 825 when the then Mercian king was overthrown by a West Saxon. The first of a long line of West Saxon kings with their seat in Winchester was Egbert. Of all these the most prominent in a cultural sense is Alfred who if not himself a great scholar was at least responsible for the flowering of learning in Wessex in the late ninth century and for the rise of the West Saxon dialect of Old English as a koiné (dialect used as a quasi-standard in those areas outside its own native one).

The invaders certainly prevailed over the natives so far the language was concerned; the linguistic conquest was complete. After the settlement West Germanic tongues came to be spoken all over Britain with the exception of a few distant regions where Celts were in majority: Scotland, Wales and Cornwall.

The migration of the Germanic tribes to the British Isles and the resulting separation from the Germanic tribes on the mainland was a decisive event in their linguistic history. Geographical separation, as well as mixture and unification of people are major factors in linguistic differentiation and formation of languages. Being cut off from related Old Germanic tongues the closely related group of West Germanic dialects developed into a separate Germanic language, English. That is why the Germanic settlement of Britain can be regarded as the beginning of the independent history of the English language.

The dialects of Old English are more or less co-terminous with the regional kingdoms. The various Germanic tribes brought their own dialects which were then continued in England. Thus we have a Northumbrian dialect (Anglian in origin), a Kentish dialect (Jutish in origin), etc. The question as to what degree of cohesion already existed between the Germanic dialects when they were still spoken on the continent is unclear. Scholars of the 19th century favoured a theory whereby English and Frisian formed an approximate linguistic unity. This postulated linguistic entity is variously called Anglo-Frisian and Ingvaeonic, after the name which Tacitus (c.55-120) in his Germania gave to the Germanic population settled on the North Sea coast. Towards the end of the Old English period the dialectal position becomes complicated by the fact that the West Saxon dialect achieved prominence as an inter-dialectal means of communication.

2014-09-04

2014-09-04 2564

2564