1. England under the Normans.

2. Middle English dialects. Rise of the London dialect.

3. Writings.

4. Changes in spelling and phonetics.

5. The main trends of grammar development. Parts of speech and means of form-building.

1. After Canute’s death in 1042 his empire collapsed and the old Anglo-Saxon line was restored to the English throne but their reign was short-lived. The new English king, Edward the Confessor (1042-1066), had been reared in France and had strong family links in Normandy in Northern France. Once on the English throne, he brought over many Norman advisors and favourites. It was rumoured that he appointed William of Normandy his successor. However, the government of the country was still in he hands of Anglo-Saxon feudal lords, headed by the powerful Earl Godwin of Wessex who was a distant relative of Edward.

In 1066 (1065?), when Edward died leaving no heirs, the Elders of England proclaimed Harold Godwin king of England. At the same time William, Duke of Normandy, who also was a relative to the Anglo-Saxon dynasty, laid his claim to the English throne as well. He mustered a big army by promise of land and plunder (one third of his soldiers were Normans, others, mercenaries from all over Europe) and, with the support of the Pope, landed in Britain. Harold was squeezed between two fronts: the Vikings were attacking in the North and he rushed to defend his land and won a historic battle at Stamford bridge, but meanwhile, William of Normandy had landed in the south and won a great victory at Hastings.

In the battle of Hastings, fought in October 1066, Harold was wounded in the eye and soon died and the English were defeated. This date is officially known as the date of the Norman Conquest, though the military occupation of the country was not completed until a few years later. William the Conqueror was crowned King of England on Christmas Day 1066.

Normandy, which is situated in the north of France, got its name after it has passed into the hands of the Vikings under the treaty of 912 (‘Norþmann’ – a man from the north). Normandy was a dukedom of feudal France and the Scandinavians assimilated with the local population, took over their language and culture. When they came to England they were French speaking, with French feudal mode of life.

The new king managed to crush the remaining Anglo-Saxon resistance and gave land to his Norman nobles in return for duty or service, organizing the country according to the feudal system.

After the conquest hundreds of people from France crossed the Channel to settle down in Britain. Immigrants were supported by the Norman kings of Britain who were also dukes of Normandy. Due to the process still closer contacts with the Continent were established. French monks, tradesmen and craftsmen flooded the south-western towns, so that much of the population was French. Any attempts of uprisings or rebellions were cruelly suppressed with leader killed in fights or executed afterwards. Some of the Anglo-Saxon nobility escaped to France, the rest were subdued. People in countryside were mostly enslaved. Towns population included both French and English craftsmen whereas the ruling class – feudal aristocracy and clergy – consisted of the Normans only.

The fourteenth century was a difficult period for England because of both the Black Death (bubonic plague) and a long series of wars, which were a disaster for the economy and led to the existence of large armed gangs terrorizing the countryside and destabilizing the political situation.

The Hundred Years War against France (1337-1453) saw many ups and downs but for Britain it ended in the loss of all its possessions in France apart from the port of Calais. The plague killed about one third of the whole population of Britain, and it was followed by other minor epidemics. Over the whole of the fourteenth century, the population fell from about 4 million to less than 2 million.

This decrease in population, however, was favourable for labourers: the manpower shortage meant that they could sell their services at a higher price and peasant life became more comfortable. The king and the parliament did not succeed in trying to stop the rise of labour costs and the landowners had to rent their land for longer and longer periods. The process led to the gradual dying out of landowner as a social class. Their place was occupied by a new class, the 'yeomen', or smaller farmers, who became the backbone of English society.

The Peasants' Revolt in 1381 was the result of the "poll-tax" to be paid by everyone in the country. Led by Wat Tyler, who called for better treatment of the poor comparing their life in the kingdom with animals' life, the rebellion lasted four weeks and the peasants managed to take control of much of London. The young king, Richard II, promised to satisfy the peasants' demands and abolish serfdom and the rebelled believed him. But later, having changed his mind, Richard executed the leaders of the uprising and refused to honour his promises.

The people were also greatly dissatisfied with the corrupt, cruel and greedy church authorities. There appeared a number of works in English representing a threat to the Church authority as they allowed people to think independently.

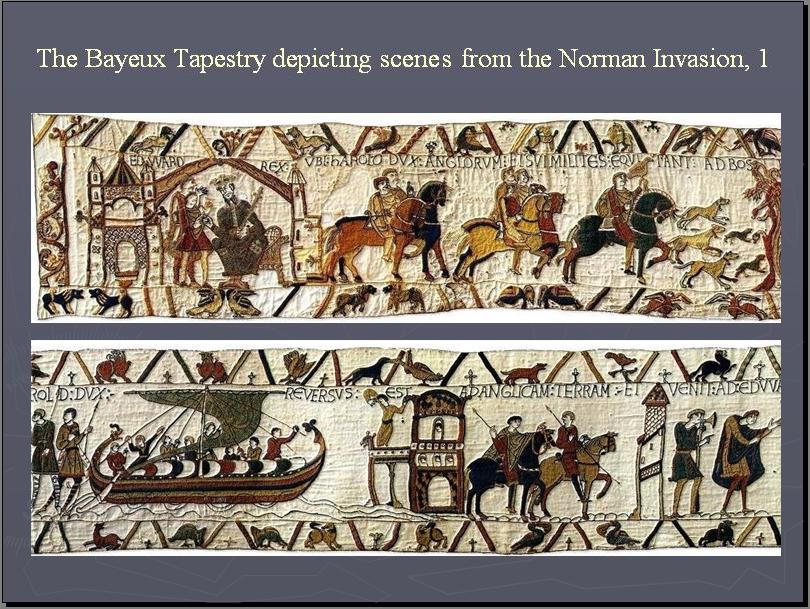

Picture 10. The story of the Norman Conquest of Britain is recounted pictorially on the Bayeux Tapestry, named after a town in Normandy where it first appeared as a decoration for the cathedral in 1476. It is some 70 metres long and 50 cm wide. The tapestry is on view in a museum in the town today. Source: www.uni-essen.de

Another series of struggles for power was the War of the Roses which took place during the mentally unstable Henry VI's reign. It was a war of aristocracy fighting for power. Nearly all the representatives of the two houses (those of Lancaster, red rose, and York, white rose) were killed in the merciless struggle. The war ended when in the battle of Bosworth Field, in 1485, Richard III was defeated by Henry Tudor, Duke of Richmond, who was crowned King Henry VII. The rule of the Tudor dynasty had begun. The Wars of the Roses almost led to the destruction of the ruling classes and enabled the Tudors to lay the foundations of a new nation.

The Norman domination in England lasted for almost three centuries and, consequently, the French language was widely used in many spheres of life. French was the official language of administration: the king’s court, the church, the law courts, the army and the castle. It was the everyday language of many nobles, of the higher clergy and of many towns-people in the south. The intellectual life, literature and education were in the hands of French-speaking people; French, alongside Latin, was the language of writing. Teaching was often conducted in French and boys at school translated Latin into French instead of English.

Anyway, the native population, being illiterate, continued speaking English. The English language was used for spoken communication only.

At first the two languages existed side by side without mingling. Then, gradually, they began to penetrate each other. The Norman barons and the French town-dwellers had to use English words to be understood, and the English began to choose French words in current speech. A person speaking French fluently was considered to be one of higher standing and that gave him a certain social prestige. Probably many people became bilingual and had a fair command of both languages.

2. In early Middle English there existed three languages side by side: English, French (Anglo-Norman) and Latin. All the English dialects were equally used by local population for everyday communication but they were not used as the state language. All the state documents, laws were written in Anglo-Norman, it was the language of the parliament and education. Latin was the language of the church and science.

The most important extralinguistic fact for the development of the Middle English dialects is that the capital of the country was moved from Winchester (in the Old English period) to London by William the Conqueror in his attempt to diminish the political influence of the native English. Nevertheless, with the growing assimilation of the Normans they started using English in those layers of the society which had not witnessed the vernacular before. The first state document written in English was Proclamation of 1258 (of King Henry III). It was written in the London dialect which at that time was closer to the south-western dialect though also included some elements of the East Midland one. In XIV century schools gradually begin using English as a language of teaching; meanwhile English was from time to time spoken in the parliament.

In Early ME the differences between the regional dialects grew. It was the age of poor communication between the inhabitants in different parts of the country which was very favourable for dialectal differentiation. In those days dialect boundaries often coincided with geographical barriers such as rivers, marshes, forests.

The main dialectal division in Middle English is basically a continuation of that of Old English. The following dialect groups can be distinguished in Early ME: Southern, Midland (or Central) and Northern.

The Southern group included Kentish and the South-Western dialects. Kentish was a direct descendant of the OE dialect known by the same name and having more or less the same geographical distribution. The two most notable features of Kentish are (1) the existence of [e:] for Middle English [i:] and (2) so-called "initial softening" which caused fricatives in word-initial position to be pronounced voiced as in vat, vane and vixen (female fox). The South-Western group was a continuation of the OE West Saxon dialects. The area covered in the Middle English period is greater than in the Old English period as inroads were made into Celtic-speaking Cornwall. This area becomes linguistically uninteresting in the Middle English period. It shares some features of both Kentish and West Midland dialects.

The group of Midland (Central) dialects – corresponding to the OE Mercian dialect – is divided into West Midland and East Midland as two main areas, with further subdivision within: South-East Midland, South-West Midland, North-West Midland and North-East Midland. West Midland is the most conservative of the dialect areas in the Middle English period and is fairly well-documented in literary works. It is the western half of the Old English dialect area Mercia and characterized by the retention of the Old English rounded vowels [y:] and [ø:] which in the East had been unrounded to [i:] and [e:] respectively.

East Midland is the dialect out of which the later standard developed. To be precise the standard arose out of the London dialect of the late Middle English period. The London dialect of the XIII century is mainly characterized by the south-western features whereas in the XIV century it evidently was based on the East Central dialects. Having absorbed the features of many dialects it was in the least degree influenced by the West Central dialects. The London dialect of the period was a mixture of components of different dialects: it witnessed the coexistence of pronunciation norms and grammatical forms originating from different dialects, e.g. OE brycg (NE bridge) could be spelled both as bridge (East Central variant)and bridge (Kentish); hwylc and swylc are preserved today as which and such – the first is from the East Central dialect, the second is from South Western; the spelling of busy and bury reflect that of the South-Western dialect whereas the pronunciation is borrowed in the first case from East Central and in the second from Kentish.

The explanation for the change of the dialect type and for the mixed type of London English lies in the history of London population. The fact is that in the middle of the XIV c. London was practically depopulated during the epidemic of plague known as "Black death" (1348) and later outbreaks of bubonic plague. The highest proportion of the dead occurred in London. After the epidemic the city was re-inhabited by newcomers from the East Midlands. The result was that the speech of Londoners was brought much closer to the East Midland dialect.

The London dialect of the first half of the XIV century is presented by the works of Geoffrey Chaucer, John Gower and John Wycliffe.Later it developed into what is called Cockney today while the standard became less and less characteristic of a certain area and finally (after the 19th century) became the sociolect which is termed Received Pronunciation.

The Northern dialects had developed from OE Northumbrian. In Early ME the Northern dialects included several provincial dialects, e.g. the Yorkshire and the Lancashire dialects and also what later became known as Scottish. By Middle English times English had spread to (Lowland) Scotland and indeed led to a certain literary tradition developing there at the end of the Middle English period which has been continued up to the present time (with certain breaks, admittedly). The dialects are characterized by retained velar stops (i.e. not palatalised) as can be seen in word pairs like rigg/ridge; kirk/church.

3. Not much has been preserved of literature in English from the first century after the Norman conquest. Presumably there was a tradition of writing in the vernacular, but few examples have survived. Manuals of religious instructions in prose continued to be written. As there was great interaction between English, French and Latin a wide range of classical literature and literary theory became available to the English.

A new genre of secular literature to emerge in Early Middle English was that of the metrical romance (romance of chivalry), exemplified in Layamon's Brut which deals with the legendary story of King Arthur, believed to be descended from Brutus. The romances were long compositions in verse and prose, describing the life and adventures of knights (Brut, Havelok the Dane, King Horn). These romances were forerunners of the novel and show a shift of values from the Old English epics, such as Beowulf.

Chivalry denoted a set of values which a perfect knight was to respect: the knight would defend any 'damsel in distress' (any woman in difficulties), he would avenge any insults to his good name and honour, and would serve God and the king. The cult of 'courtly love', chaste and near-fanatical service to one's lady, had a great influence on the literature of the period.

Mere bravery was not any longer the only theme to be emphasized in literature. Writers and philosophers began to explore the nature of love, religious and profane. There appeared new poetic forms borrowed from France ('carole', a form of dance-song), the fabliau and the allegorical poem.

Geoffrey Chaucer dominates the period, he is known as the founder of the English literary tradition, and the period as "the age of Chaucer". Chaucer was born in London and wrote his works in the London dialect. His "The Canterbury Tales", "A Legend of Good Women", etc. were copied many times and delivered to different parts of the country. This fact could not but play an important role in spreading the written form of the London dialect all about Britain.

John Wyclif was another outstanding author of the period. He is best known for his translation of the Bible in which he criticized the Pope and the clergy for their immorality. His translation was read in all parts of the country by representatives of different social layers: craftsmen, merchants, clergy, aristocracy. Later the translated Bible was prohibited and Wyclif's followers punished.

Other writings of the Middle English period are not very valuable as literary works but they are very important for studying the language of the period. They are mainly of religious nature. A great number of these works are homilies, sermons in prose and verse, paraphrases from the Bible, psalms and prayers. The earliest of them is the "Moral Ode" representing the Kentish dialect of the late 12th or the early 13th century.

The East Midland dialect is exemplified in "The Peterborough Chronicle" (1070-1154) which is the continuation of "The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle". "Ormulum" (the beginning of XIII c.) is a religious poem containing long and naïve explanations and digressions, it is of special interest for linguists as its author, Orm, systematically uses a newly invented system of sound alternation: a short vowel is followed by a doubled consonant, a long one – by a short consonant. It is argued whether it is used to show the length of a vowel or the length of the consonant. Here are the initial lines from "Ormulum" to illustrate the phenomenon mentioned:

Nu, broþurr Wallter, broþurr min Aefterr the flæshess kinde… -

Теперь, брат Вальтер, брат мой по родству во плоти…

Besides, the East Midland dialect is preserved in the rhymed novels "King Horn" and "Havelok the Dane" (XIII c.).

"Sir Gawaine and the Green Knight" is an alliterated romance of chivalry written in XIV c.; another romance of chivalry, "William of Palerne", also contains alliterated verse. These works are in the West Midland dialect, which is also represented by a number of shorter poems under the common heading of "Alterative Poems".

The main work in the West Midland dialect is, though, the long satirical poem called "The Vision of William Concerning Piers, the Plowman". It is directed against corruption in the church and at court. Its author is William Langland, who was born in Western England, but for a long time lived in London, so his poem contains the elements of the both dialects.

The South-Western dialect is represented by Layamon's "Brut" (beginning of the XIII c.) telling about Caesar's friend, Brut, who later killed him and who was supposed to have been the first to come to Britain to settle there with his close friends. "Ancrene Riwie" (beginning of the XIII c.) is addressed to three nuns coming from aristocratic families. Robert of Gloucester's "Chronicle" (end of XIII c.) paraphrases the Celtic legends and describes historical events.

The Kentish dialect is represented by Dan Michel's "Ayenbite of Inwit" ("Угрызения совести"), XIV c., William of Shoreham's translations of French poems.

The works in the Northern dialect include "Cursor Mundi" ("Бегущий по свету"), XIII c., a rhymed poem telling a legend from the Bible; Richard Rolle de Hampole's "The Pricke of Conscience" ("Угрызения совести"), the first half of the XIV c., a religious poem; the XIV-XV c. mysteries "Townley Plays" ("Таунлейские мистерии") and "York Plays" ("Йоркские мистерии"), the language of which is close to colloquial.

The first written records in the Scottish dialect are dated back to XIV century. It embraces many characteristic features of a northern dialect. Having once appeared as a local variant of a northern dialect it inevitably turned into a separate dialect due to the geographic position of Scotland. The first written record in the Scottish dialect is "The Bruce" composed by Barbour at the end of XIV century. It is a poem about the national hero Robert Bruce who fought for his country's independence. The dialect is also represented by the poems of the beginning of XV century entitled "The Kingis Quhair" ("Королевская книга").

4. The most fundamental difference of the Middle English pronunciation and spelling from modern lies in the fact that Middle English is much more phonetic: vowel sounds are pure (more like, for example Italian vowels than the diphthongized equivalents in Modern English) and consonants are generally all pronounced and not elided as in Modern English. Initial kn- and gn- have their full value (i.e., the k or g is sounded); w is pronounced before r, gh was pronounced like the– ch in Scottish 'loch' and r was pronounced more strongly, in all positions (often silent in modern English: girl, bird etc.).

Fricatives [v, z, ð] which occurred in the middle of the word were allophones in Old English, e.g. līf ‘life’ ended in [-f] whereas libban — cf. the preterite form with the voiced fricative lifde — had an internal voiced fricative [-v-]. With the loss of the inflectional endings the verb was reduced to a single syllable and the final /-v/ now contrasted with the final /-f/ of the noun, and this resulted in the change in status of voice among fricatives in Middle English which from then on distinguished phonemes.

With French loans instances of voiced initial fricatives began to occur in English, and this strengthened the status of voiced and voiceless fricatives, e.g. vertu ‘virtue’ vileynye ‘villainy’ zēle ‘zeal’.

Middle English also witnessed the loss of distinctive consonant length. In Old English consonants could be long or short, e.g. /-s-/ [-z-] and /-ss-/ [-ss-] were phonemically distinct, e.g. Offa (proper name), missan ‘miss’, siþþan ‘sit’ which show geminates (long consonants) for all three fricative types in Old English. In Middle English this distinction begins to be lost so that voiceless geminates found in the middle of the word were reduced to simple segments but remained voiceless, so there remained the distinction between voiced and voiceless fricative in medial position, thus strengthening the phonemic significance of voice for these fricatives. Later initial /θ-/ in grammatical formatives such as the, there, that, etc. was softened to [ð] because of the unstressed character of the words. Thus the series /v-, ð-, z-/ in initial position was completed.

The system of vowels underwent profound qualitative and quantitative changes in Middle and Early New English. The main direction of the evolution of unstressed vowels consisted in losing their former distinctions in quality, sometimes in quantity. The tendency towards phonetic reduction was particularly strong in unstressed final syllables in Middle English.

In Old English five vowels in an unaccented position could be distinguished: [e, i, a, o, u]. In Middle English the phonemic contrast between them was practically lost and there remained only two unstressed vowels, [ə, i] which were never directly contrasted. The final [ə] disappeared in Late Middle English though it continued to be spelt as –e and it was understood as a means of showing the length of the vowel in the preceding syllable and was added to words which did not have this ending before: OE stān, rād and ME stoon, stone, rode (NE stone, rode). The table below illustrates the differences in the pronunciation of unstressed vowels in the three historical periods.

Table 12 (Source: Rastorguyeva 2002)

| Old English | Middle English | New English |

| fiscas fisces | fishes ['fi∫əs] or [fi∫is] fishes | fishes pl fish's Gen. sg |

| rison risen | risen ['rizən] risen | rose (OE Past pl) risen (Part. II) |

| talu tale talum | tale ['ta:lə] talen | tale (OE Nom. and other cases sg, Dat. pl) |

| bodig | body ['bodi] | body |

The system of stressed phonemes was subjected to considerable changes in Middle English. Long vowels were the most changeable ones. They always displayed a tendency to become narrower and to diphthongize, whereas short vowels displayed a trend towards greater openness. Early Middle English is mainly characterized by positional quantitative changes of monophthongs (before a consonantal cluster of a sonorant and a plosive short vowels were lengthened; the other groups of two or more consonants produced the reverse effect; short vowels became long in open syllables); at the same time profound independent changes affected the system of diphthongs: OE diphthongs were monophthongised and lost, and new types of diphthongs developed from vowels and consonants.

In Late Middle English there began a series of new changes; independent qualitative changes of all long vowels known as the "Great Vowel Shift"; it lasted from the 14th till the 17th (18th) century. Numerous positional vowel changes of this period gave rise to a new set of long monophthongs and diphthongs. The shift involved the change of all Middle English long monophthongs and some of the diphthongs. Table 13 illustrates the shift of vowels in Middle English.

Table 13

The Great Vowel Shift (Middle English)

| Changes of vowels | Examples | |||

| Middle English | Intermediate stage | New English | Middle English / New English | NE |

| i: e: ε: a: כ: o: u: au | e: | ai i: i: ei ou u: au כ: | ['ti:mə] – [taim] [['findən] – [faind] [ri:den] – [raid] [t∫i:ld] – [t∫aild] ['ke:pən] – [ki:p] ['fe:ld] – ['fi:ld] [sle:pen] – [sli:p] [he:] – [hi:] [strε:t] – [stri:t] [ε:st] – [i:st] ['stε:lən] – [sti:l] [mε:l] – [me:l] – [mi:l] [mε:t] – [me:t] – [mi:t] ['ma:kən] – [meik] ['ta:blə] – [teibl] [na:m] – [neim] [ta:k] – [teik] [stכ:n] – [stəun] [כ:pən] – [əup ə n] [sכ:] – [səu] [rכ:d] – [roud] [bכ:t] – [bout] [mo:n] – [mu:n] [go:s] – [gu:s] [so:n] – [su:n] [mu:s] – [maus] ['fu:ndən] – [faind] [nu:] – [nau] [hu:s] – [haus] ['kauz(ə)] – [kכ:z] ['drauən] – [drכ:] | time find ride child keep field sleep he street east steal meal meat make table name take stone open so rode boat moon goose soon mouse find now house cause draw |

5. The grammar system in Middle English and Early New English underwent considerable changes. For the nominal parts of speech the main direction of development in all periods of history was simplification. Simplifying changes began in Proto-Germanic times, continued at a slow rate in Old English and were intensified in Middle English. In Middle English and New English we observe the process of the gradual loss of declension in all the declined parts of speech. As a result, in Middle English there remained only three declinable parts of speech (noun, adjective and pronoun) against five in OE (the mentioned above plus the infinitive and the participle).

In Old English the grammatical categories were indicated by means of inflections and the loss of the latter implied that something took their place. But what? The answer is simple: word order and the increased functionalisation of prepositions. In Old English the order Subject - Object - Verb was common but with the loss of inflections the identification of Subject and Object was not always that simple. For this and other contributory reasons the order Subject - Verb - Object became more usual in the course of Middle English. The order Verb - Subject - Object which was also found in Old English declined in frequency, remaining after adverbs where it is still sometimes found today in inversed sentences, e.g. Hardly had he left the room when she rang.

An interesting fact is that the morphology came to play less and less of a role in the indication of grammatical categories. This development was triggered by the attrition of inflections. This resulted in the fact that the remaining inflections changed their meaning and functions and were employed for semantic purposes. A clear example of this is provided by the present tense -s in many dialects of English (but not in the standard). Here there is frequently a contrast between present tense verb forms without any endings and those with a generalised -s for both numbers and all persons. The semantic distinction is between an unmarked present (no ending) and a narrative present (with the inflectional -s), e.g. She have no time for the children anymore. They walks out the door and they meets him coming up the drive. Still other dialects distinguish between an unmarked present and a habitual aspectual present with the - s ending: The lads works the night-shift in the summer if they can.

The verb system was developing in two directions. On the one hand, many of the verb inflections dropped out of use due to the appearance of new analytical ways of form-building. Such simplification of forms made verb conjugation more regular. The OE morphological classification of verbs practically died out. On the other hand, the paradigm of the verb grew as new grammatical categories and forms appeared. The verb acquired the categories of Voice, Time Correlation (Phase) and Aspect. Within the category of Tense there appeared the form of the Future Tense and in the category of Mood there arose new forms of the Subjunctive.

The main changes at the syntactical level were: the rise of new syntactic patterns of the word phrase and sentence; the growth of predicative constructions; the development of the complex sentences and of diverse means of connecting clauses.

In general, during the periods of Middle English and Early New English the language developed from a synthetic into an analytical one with analytical forms and ways of word connection prevailing. The analytical forms included: combinations of form and notional words, word order and special use of prepositions.

The parts of speech to be distinguished in Middle English were the same as in Old English: the noun, the adjective, the pronoun, the numeral, the verb, the adverb, the preposition, the conjunction and the interjection. The only new part of speech to appear was the article which developed from the pronouns in Early Middle English.

The means of form-building also changed a lot. In Old English all the ways of form-building were synthetic. In Middle English and Early New English grammatical forms could also be built in the analytical ways, with the help of auxiliary words. New synthetic forms were not developing, so gradually the analytical forms began to prevail.

The preserved synthetic means of form-building were as before: inflections, sound interchanges and suppletion. Only prefixation once used to mark Participle II went out of use in Late Middle English. Inflections were still used in all the changeable parts of speech but their number became less varied. Sound interchanges were not productive, they occurred in verbs, nouns and adjectives; a number of new interchanges arose in Early Middle English in some groups of weak verbs. Suppletion was found in some surviving from Old English words.

The analytical way of form-building was a new device, which developed in Late Old English and Middle English and since those times occupy a most important place in the grammatical system. Analytical forms developed from free word groups (phrases, syntactical constructions), the first component in which gradually lost its lexical meaning and acquired a new grammatical value in the compound form. Analytical form-building was productive in verbs but did not affect the noun.

Additional reading…

The Norman Invasion.

The beginning of the Middle English period can be seen from a linguistic and an historical point of view. Linguistically various features began to become evident around the turn of the millennium such as the lengthening of vowels before clusters of a sonorant and a homorganic consonant. Sociolinguistic features also played a role here such as the demise of the Winchester standard (the West-Saxon koiné of the late Old English period). This did not happen suddenly but was an ongoing process as of the 11th century and which was carried to its conclusion with the Norman invasion. The mention of this last fact brings us to the main historical event which can be singled out as the onset of the Middle English period. The one indisputable fact of this early time is the invasion of England by the Normans in 1066.

|

William was the son of Robert the Devil who in turn was the great- great-grandson of Rollo of Denmark and who was made the first duke of Normandy with an agreement in 912 after having waged war against the French under Charles the Simple just like his Viking cousins had done against Alfred in England. With the assimilation typical of all Vikings, the Normans soon became French and learned the local dialect so that by the time of the invasion of England they were well and truly French-speakers just as the Viking settlers in Ireland became Irish-speakers.

There were certain not too tenuous ties between England and Normandy in the period preceding the invasion. Thus in 1002 Æthelred the Unready married a Norman princess and finally settled in Normandy. His son Edward the Confessor was brought up in France and had many Frenchmen in his retinue. Perhaps of this French connection, William of Normandy felt that his claim to the English throne was legitimate. Resolute as he was, William decided to invade England and enforce his claim by these direct means. After mustering an army of some considerable size, he landed in England at Pevensey in the south in September of 1066. In the beginning the invasion was uncontested. Harold was busy in the north of England with an invasion by the king of Norway (yet another claimant to the throne). When Harold had dealt with this menace from the north he was faced with that from the south. He moved south and tried to gather as many fighters as possible on the way. This was not very successful and Harold was forced to face the Normans with only a medium sized army. The engagement was between London and the approaching Norman army, near the town of Hastings, on a hill at Senlac. The actual battle began in the morning and went well for the English well into the afternoon, given their advantageous position on the hill. Then the French feigned a retreat, thus luring the English out of their vantage point. They advanced then and succeeded in getting the upper hand not least because the leader of the English, Harold, was killed when a Norman arrow struck him in the eye. The English were routed and the French were victorious by nightfall. William in true medieval warfare fashion continued to pillage and plunder the south east of England until London capitulated and decided to accept him as king of England. He was crowned king of England on Christmas day 1066.

The battle of Hastings was the last invasion of England by foreigners (the previous ones having been, the Celtic invasion in the centuries before Christ, the Roman invasion of Caesar in 55 BC and later Roman invasions in the 1st century AD and the Germanic invasions which began in the mid 5th century). What this meant is that it resulted in the last direct influence of a foreign language on English. All later influences are due to written forms of language, Latin and Greek loanwords, later French words, etc. The aftermath of the battle of Hastings is almost as important as the battle itself. While it is true that it represents the turning point in the fortunes of the native English it is the activities of the following years which are of greatest importance for the development of England and the English language.

Immediately after his conquest over the English, William started with replacing the English aristocracy by Norman lords. Those who did not willingly submit to the new masters were killed. The language of the newcomers was Norman French; English was banished from court usage and declined into a patois (an unwritten dialect).

The consequences of this for the fate of the language were enormous. As everywhere in the Middle Ages, the native language was only written at court and in the monasteries. The latter were not spared the brutal re-structuring which William forced on the English as we know from the last entries of the Anglo-Saxon chronicle. Manuscript copying in English virtually ceased and at the court all legal texts were prepared in French.

This is the period of the oldest French loans, i.e. that of the strictly Norman loans. The degree to which the Norman language of the time fused with English is a matter of debate and the views on this range from a creole theory, which postulates that for a time the fusion was perfect and people spoke a true mixture (Anglo-Norman) as a mother language, to a two-tier view which maintains that English and Norman were fairly well kept apart due to the splitting of the two languages according to class. Later on an influence was still to be felt but it was not the direct influence of this early period but the written influence of central French.

The position of French in England was strengthened by the fact that the political connections with the continent were particularly strong. William himself married Eleanor of Aquitaine and thus remained tied to France. His successors, notably Henry I (1100-1135), Stephen (1135-1154) and Henry II (1154-1189) spent a large part of their lives abroad, i.e. in France. The aristocracy having being exchanged immediately after William’s arrival remained French in language, outlook and loyalty. However, the attitude to the English language was one of more or less indifference. William tried, as legend has it, to learn English in his forties but gave up the effort. Members of the court could sometimes speak English but did not particularly exert themselves in this respect. Literature at the court of London was largely French in the period up to around 1200. The real question which interests the linguist and which cannot unfortunately be answered with any great amount of clarity is to what extent French was spoken by the population at large. We can safely assume that there was a certain amount of knowledge of French from the 13th century onwards. Various items of evidence support this. For example from about the middle of the 13th century textbooks and grammars of French begin to appear. In literature reference is made to people speaking both English and French though this is usually by poets and writers whose audience would tend to be middle and upper class anyway.

When considering the question of the dissemination of French we can point to the traditional division of England into north and south. French was most readily spoken in the south and south east (as might be expected, given the geographical proximity to France).

Source: www.uni-due.de

2014-09-04

2014-09-04 3984

3984