History of English as a subject is connected with history of England, English literature, theoretical phonetics, grammar and lexicology. It shows phonetic, grammatical and lexical phenomena as they developed. When discussing the history of the English language one necessarily deals with such concepts as synchrony (modern state of the language) and diachrony (process of evolution) which were introduced at the beginning of the XX century by Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) in his work on language "Course in General Linguistics". F. de Saussure considered that the aim of general synchronic linguistics was to set up the fundamental principles of the constituents of any language. "To synchrony belongs everything called 'general grammar', for it is only through language-states that the different relations which are the province of grammar are established... The study of static linguistics is generally much more difficult than the study of historical linguistics. Evolutionary facts are more concrete and striking; their observable relations tie together successive terms that are easily grasped; it is easy, often even amusing, to follow a series of changes. But the linguistics that penetrates values and coexisting relations presents much greater difficulties. In practice a language-state is not a point but rather a certain span of time during which the sum of the modifications that have supervened is minimal... " (From: Saussure F. de. Course in General Linguistics. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1974). Diachronic linguistics studies, according to Saussure, not relations between terms of a language existing in one period of time but relations between successive terms that are substituted for each other in time... Phonetics, Saussure believed, was the prime object of diachronic linguistics.

Ferdinand de Saussure compared language with the game of chess. "First, a state of the set of chessmen corresponds closely to a state of language. The respective value of the pieces depends on their position on the chessboard just as each linguistic term derives its value from its opposition to all the other terms. In the second place, the system is always momentary; it varies from one position to the next... Finally, to pass from one state of equilibrium to the next, or -according to our terminology-from one synchrony to the next, only one chesspiece has to be moved; there is no general rummage... In a game of chess any particular position has the unique characteristic of being freed from all antecedent positions; the route used in arriving there makes absolutely no difference; one who has followed the entire match has no advantage over the curious party who comes up a critical moment to inspect the state of the game; to describe this arrangement, it is perfectly useless to recall what had just happened ten seconds previously. All this is equally applicable to language and sharpens the radical distinction between diachrony and synchrony." (From: Saussure F. de. Course in General Linguistics. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1974)

Today the diachronic development of the language is understood as the evolution of its different levels, and the synchrony of the tongue is its statics at a definite period, e.g. today.

The method employed in studying the history of the language is called comparative linguistics. The scientific means came into existence in the XIX century due to the prominent German scholars Franz Bopp (1791-1867) and Jacob Grimm (1785-1863). It proved to be of great use in the development of general linguistics. It was also a starting point for the history of language as a science. In the first half of the XIX century European linguists began to compare ancient and modern European languages: Latin, French, German, Russian and others. Sanscrit was of great help when it was opened. European linguists could not fail to notice the fact of regular similarities between some languages and Sanscrit. It appeared that some languages had similar features in their vocabulary, at phonetic and grammatical levels. In the European languages the subject of the sentence is usually in the nominative case, so they are called nominatival languages; many words are from the same roots (English night – German Nacht – French nuit – Polish noc – Bulgarian нощта – Russian ночь; English cold- German kalt- Russian холодный; English mother – German mutter – French mere – Russian мама); many grammatical features are very much alike. Proto-Germanic which is the parent language of modern English was reconstructed by means of comparative linguistics. Much to the comparative study of languages was contributed by the Russian scholar A.C.Vostokov (1781-1864).

The method of comparative linguistics implies that languages do not develop uniformly. Language development is sometimes slower, sometimes faster. There are periods in the history of every language when it undergoes a lot of changes, but there are other periods when the innovations are few. The method of comparative linguistics can be applied only when there are written documents. It is not universal.

The discovery of kinship of the Indo-European family enabled linguists to work out a classification of languages according to their descent and kinship. The classification is called genealogical. According to it languages are divided into families. A family consists of languages which developed from tribal dialects of ancient people. A family includes several groups of languages characterized by similar features at different linguistic levels. The Indo-European family of languages (which are spoken by approximately 46 % of world population) is divided into several groups, Germanic, Slavic and Romanic among them, the English belonging to the Germanic group. The former group is also represented by German, Swedish, Norwegian, Africaans, Netherlandish, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic, Frisian, Faroese and Yiddish. The Slavic group is represented by Russian, Ukrainian, Byelorussian, Polish, Czech, Bulgarian and some others. The Roman group is represented by Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Romanian.

Another classification is called morphological and it is based on the morphological structure of the word.

The main source in studying the history of the language is written documents. They give a clear picture of the vocabulary and grammatical structure of the period. As for the phonetic structure they do not always present a clear enough picture of spelling and pronunciation because they often do not coincide. In this case private letters, diaries containing illiterate spelling which reflects pronunciation can be of great help. Besides, linguists also use rhymes, children songs, descriptions of sounds.

2. The evolution of the language is made up of diverse facts and processes. The history of the language may be divided into internal and external. External development includes all the facts which can be referred to and connected with functioning of the language in speech community: the spread of the language in geographical and social space which is directly connected with history of the nation (political, social life, economic, cultural development, trade, contacts with other peoples, wars, conquests, progress in science, etc.), the differentiation of language into functional varieties (geographical variants, dialects, standard and non-standard forms, etc.). When discussing the external history of the language we should remember that every language functions in the language space, defined by T.A. Rastorguyeva as “the geographical and social space occupied by the language”; its development is also connected with the concept of linguistic situation which “embraces the functional differentiation of language and the relationships between the functional varieties”.

Internal development of the language is also called structural development and it is connected with the division of language system into subsystems: the phonetic level, the morphological level, the syntactic level and the lexical level. Accordingly, the internal development of the language can be represented by historical phonetics, historical morphology, historical syntax and historical lexicology.

Linguistic changes usually proceed at minor steps, they are slow and gradual, as demanded by the communicative function of the language, otherwise these changes would have been an obstacle in communication between generations. Anyway, the rate of linguistic evolution varies from one historical period to another being connected with different events.

An important thing to note here is that different language levels do not develop uniformly. The vocabulary of the language is the subsystem which is most subjected to alterations of various kinds. New words are easily borrowed in periods of intercultural contacts; new words are built with the help of the existing means of word building; the new meanings are acquired by the old words with new inventions, with the appearance of new concepts.

The system of phonemes and morphemes are much slower to change that can be explained by the fact that these units are closely interconnected and interdependent, opposition between the phonemes is required for the distinction of morphemes which means that one alteration causes the other. Grammar is the most abstract of the linguistic levels and it must be stable enough to provide stable devices for arranging words into classes and for connecting them into sentences. Lexical units (words) are independent, e.g. the process of borrowing does not necessarily involve any other alterations.

The two main factors, the driving forces of the language historical mutation are continuity (преемственность) and causality (причинность). The first term may be decoded in the following way. Generally, the phonemes and the morphemes of the language preserve the components and the processes which characterize the parent language and the related tongues. For example, the principle of making plural forms in nouns are similar in Indo-European languages (endings of plurality are employed for the purpose); in Indo-European languages there are many words with identical roots (English night - German nacht- French nuit - Italian notta - Russian ночь - Bulgarian нощта). As a consequence, to understand the main characteristics of the Germanic languages, including English, it is necessary to trace back the phenomena under consideration.

The second factor is closely connected with the first one. Any historical study of the linguistic facts is not only aimed at discovering the stages of their development but also at finding the reasons of all the alterations, at explaining their result.

The reasons (or causes) of linguistic changes are usually divided into external and internal. External causes are connected with the history of the nation, with the various events in people’s life.

The internal causes are those which are predetermined by the language system, they are stimulated by the processes arising from the language itself, e.g. the weakening of noun declensions in English was caused by the fixation of word stress on the first syllable in the Germanic languages that was followed by the poor articulation of endings; the decline of the adjectival system of declensions was caused by the decline of noun declensions, etc. Internal factors can be subdivided into general (operating in all languages) and specific (operating in one language or a group of related languages at a certain period of time). The most general cause of language evolution is in the tendency to improve the language technique, e.g. simplifying phonetic changes (indistinct articulation and later dying out of distinctions of unstressed vowels in English). The other internal tendency is to preserve the language as a means of communication. These tendencies provide language stability (most important words and morphemes have been retained since the earliest stage of the English language history: father, man, good, he, king, etc.; Past Simple ending –d).

There have been several theories explaining the causes of language evolution. In the first half of the XIX century philologists of the romantic trend (J.G. Herder, W. Grimm) described the history of the Indo-European languages as decline and degradation. They considered that most of these languages have been loosing their richness and grammatical forms, declensions, conjugations and inflections since the “Golden Age” of the parent language.

The representatives of another trend, naturalists (A. Schleicher and others), compared language with a living organism and associated stages in language history with stages in life: birth, youth, maturity, old age and death.

Sociologists in linguistics (J. Vendryes, A. Meillet) were of the opinion that linguistic changes are caused by social conditions and events in external history.

W.Wundt and H.Paul, representing the psychological trend, insisted that linguistic changes are caused by individual psychology and accidental individual fluctuations.

The Prague school of linguists was the first to recognize functional diversity of the language dependent on external conditions. In present-day theories much attention is paid to the variability of speech in social groups as the main factor of linguistic change.

Throughout its history the English language has undergone a lot of changes. From the language of a synthetic type into turned into an analytical one, and the process involved the numerous changes in grammar. The problem of altering the language type caused the appearance of several theories explaining the reasons for the changes.

The "phonetic" theory representatives of the XIX century saw the basis for the morphological simplification in the phonetic changes, particularly, in the reduction and loss of the unaccented final syllables caused by the stress fixation in the Germanic languages. As a result, many grammatical forms coincided that led to the difficulties in comprehending the case, gender, number and person forms. Instead of the old ways of building up the grammatical forms the new ones appeared, those of prepositions and fixed word order.

The representatives of the "functional" theory consider that the loss of endings and the appearance of the analytical forms should be explained by the fact that the endings lost their grammatical meanings and died out as useless, being ousted by the other means of denoting the same ideas. In comparison with the "phonetic" theory the "functional" theory representatives insist that the changes began at the opposite end: the grammatical inflections of the noun became useless after the prepositions had begun to fulfill their functions; the gender inflections in adjectives died out after the loss of the noun gender. The development of the system of articles led to the uselessness of the morphological division of the nouns and adjectives; some verb endings went out of use when the person and number categories were indicated analytically – with the help of an obligatory subject.

The theory of the "least effort" explains the cause of the linguistic changes by the fact that the native speakers are in constant need and search of more expressive language means as the existing ones gradually lose their expressivity. This necessity is the reason for the simultaneous use of both prepositional phrases and case forms and for the appearance of the prepositional verbs and analytical forms alongside the use of simple verb forms.

Although these theories consider the important language characteristics, the drawback of them is that they do not take into account the specific conditions of the language development in the definite historical periods.

Some scholars reckon that the reason of the English morphology simplification and the change of the language type is to be found in the external history, particularly, in contacts with other tongues. For example, in the period of the Scandinavian invasion the two languages having in common intermixed. The fact that those languages had many similar roots but differed in pronunciation and endings led to mispronouncing of the latter as the roots were considered more important. Gradually it resulted in the loss of endings.

There is also another similar theory, representatives of which ascribe the grammatical changes in English to the Old French influence. These theories, though, leave out of consideration the interdependence of the linguistic changes at different levels.

Another popular theory, the so-called "theory of progress", was put forward by O. Jesperson who was against the considerations of the Indo-European linguistic history as the process of decay and degradation and tried to show the advantages of the analytical type of language over the synthetic one. He insisted that the English language history was the only way to progress and that the language itself had reached the superior level. Jesperson believed that the development of simpler forms was the general tendency in language evolution and that the English language had reached a more advanced stage, which testified, according to Jesperson, to a superior level of thinking of English-speaking nations. This opinion was severely criticized for the racial implication. Generally, Jesperson was blamed for having altered XIX century comparativists' consideration that the Indo-European language was at a more advanced stage as it had numerous inflections.

Today a very interesting theory is put forward by Martin Nowak. He tries to find direct dependence of language forms evolution and frequency of their usage. To discover this tendency, he generated a data set of verbs whose conjugations had been evolving for more than a millennium, tracking inflectional changes to 177 Old English irregular verbs. M. Nowak finds out that of those irregular verbs, 145 remained irregular in Middle English and 98 are still irregular today. He studies how the rate of regularization depends on the frequency of word usage and comes to the conclusion that the half-life of an irregular verb scales as the square root of its usage frequency: a verb that is 100 times less frequent regularizes 10 times as fast. This study provides a quantitative analysis of the regularization process by which ancestral forms gradually yield to an emerging linguistic rule.

Besides, across 200 meanings, studied by Martin Nowak, frequently used words evolve at slower rates and infrequently used words evolve more rapidly. This relationship holds separately and identically across parts of speech for each of the four language corpora, and accounts for approximately 50% of the variation in historical rates of lexical replacement. M. Nowak proposes that the frequency with which specific words are used in everyday language exerts a general and law-like influence on their rates of evolution. His findings are consistent with social models of word change that emphasize the role of selection, and suggest that owing to the ways that humans use language, some words will evolve slowly and others rapidly across all languages.

3. History of English is traditionally divided into here periods: 1) Old English – the period beginning with the Germanic settlement of Britain (5th century) or with the beginning of writing (7th century) and ends with the Norman conquest (11th c.); 2) Middle English – begins with the Norman conquest and ends on the introduction of printing (II half of the 15th c.); 3) New English – starts after the introduction of printing and lasts to the present day.

This classification of periods is based on extralinguistic factors, on the events in the external history of England which were important for the political and economic development of the country. The XI century is known for the Norman conquest which resulted in the establishment of a new, feudal mode of life; in the XV century the War of the Roses took place which involved the decay of feudalism, the establishment of absolute monarchy and the development of bourgeois relations. Anyway, these events playing an important role in the history of the nation, cannot be crucial in defining the stages of the language development. On the other hand, it is hardly possible to work out periods based entirely on inner factors of language development. Henry Sweet, the author of the first historical phonetics and grammar of English considered that the traditional periods coincide with the morphology of the three main periods: period of “full endings”, of “leveled endings” and of “lost endings”. Nevertheless this classification cannot be accepted as the only correct one as it is based on the morphological criteria and neither phonology nor syntax are taken into account.

Sometimes history of English is subdivided into seven periods. This classification mainly coincides with the traditional one with some further subdivisions: 1) Early OE (pre-written OE; 2) OE (written OE); 3) Early ME; 4) ME (Classical ME); 5) Early NE; 6) Normalization period (Neo-Classical period); 7) Late NE (Modern English).

The first period lasts from the first Germanic invasion of Britain till the beginning of writing (5th-7th c.). It was the stage of tribal dialects of West Germanic invaders who, losing contacts with their continental neighbours were developing their own variants of language. There was no written form of the dialects.

The second historical period extends from the 8th century till the end of the 11th. The tribal dialects gradually changed into local dialects the differences between which grew. In the sphere of writing West Saxon gained supremacy.

Early Middle English starts after 1066, the yare of the Norman conquest, and covers the 12th, the 13th and the first half of the 14th centuries. Diverse dialects continued existing alongside French which became the official language in the spheres of writing and administration and lost its supremacy only by the second half of he 14th-15th century when English was restored to the position of the state language. Anyway, there is a gap in the English literary tradition in the 11th-14th centuries.

Classical Middle English lasts from the later 14th till the end of the 15th century and it is called the age of Chaucer, the greatest English medieval writer. It was the time of the restoration of English to the position of literary and state language. The main dialect used in writing was the mixed dialect of London.

Early New English lasts from the introduction of printing to the age of Shakespeare, that is from 1475 till 1660. William Caxton introduced printing in England and London English was spread quickly around the country with the first cheap printed books. It was the period of great historical events: the growing capitalist system caused the progress of culture, education and literature.

Normalisation, or Neo-Classical, period, extends from the mid-17th century to the close of the 18th century. During the 18th century the English language acquires the features of a mature literary tongue, that is differentiation into styles.

Late New English represents English of the 19th and 20th centuries and the language of today. By the 19th century the language acquired its standards having become a national literary language. The classical language of literature was strictly distinguished from the local dialects and the dialects of lower social ranks. The dialects were used in oral communication and often had no literary tradition. In the 19th and 20th centuries the English vocabulary has grown on an unprecedented scale due to historical changes especially the growth of the British Empire. There have also been the definite changes at the phonetic and lexical levels.

Additional reading…

Language and Speech

Language is a complex phenomenon with origins that are difficult to trace. Certain aspects of language, though not without controversy, are better suited to empirical investigation. Speech is one example because it requires some physical properties that can be measured in, or at least partially derived from, the fossil record.

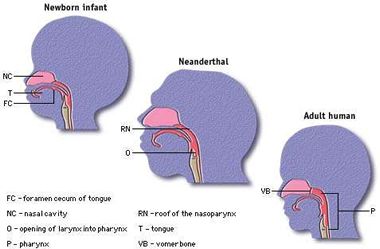

Phillip Lieberman has investigated the origin of speech for many years and has used this research to form hypotheses about the evolution of language. Lieberman suggests that speech improved greatly about 150,000 years ago when the larynx descended into the throat. According to the work of Lieberman and his colleagues, this descension improved the ability of early homonids to make key vowel sounds. Whereas the Neanderthals had a vocal tract similar in many respects to that of a new born baby, the elongated pharynx of a modern adult human is thought to enable production of a more perceptible repertoire of speech sounds. Lieberman suggests that though Neanderthals probably had some form of language, they may have failed to extend this language because they lacked the physical apparatus for producing a more sophisticated set of speech sounds. The theory that the modern human vocal tract is better suited for production of vowels has, however, recently been called into question by Louis-Jean Boe.

But the strongest part of Lieberman's argument is evolutionary rather than strictly phonetic. He points out that the descension of the larynx into the throat makes humans much more susceptible to choking than any other mammal. It is unlikely that such a dangerous adaptation would have evolved unless there was some strong selective advantage provided by it. Since the larynx contains the vocal cords and is critical for speech, it seems likely that Lieberman's hypothesis is correct in that this change somehow improved speech and that improved speech gave a distinct selective advantage, even if his hypothesis about what the exact improvements to speech were turns out to be incorrect.

Picture 1. Comparison of the supralaryngeal vocal tracts in a new born infant, Neanderthal, and an adult human.

Source: www.brainconnection.com

Major language families

The names in Italics after the Arabic numerals indicate the language families, the names in square brackets are those of the major languages of each group.

EUROPE AND ASIA MINOR 1) Indo-European (see below). 2) Finno-Ugric (Finnish, Estonian, Hungarian and various smaller languages in Russia as well as beyond the Urals, e.g. the Samoyed languages). 3) Caucasian (languages of the mountainous region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, characterized by many highly differentiated languages in a small area, Georgian [south Caucasian] is the best known of these). 4) Altaic (Turk languages) [Turkish and various other languages, such as Azeri, Uzbek, Turkmen, etc., stretching eastward of Turkey as far as the border with China, includes Mongolian and Tungusic languages]. 5) Independent The only surviving independent language in Europe is Basque which has not been proven to be genetically related to any surrounding language. From history we have other examples of language isolates, e.g. Etruscan in ancient Italy.

NORTH-EAST ASIA (SIBERIA AND ALASKA) 1) Paleo-Asiatic (consists of a few small languages spread over a vast area of eastern Siberia). 2) Eskimo-Aleut (few speakers spread over a large area stretching from Siberia through Alaska and Canada to Greenland).

NORTH AFRICA 1) Afro-Asiatic (Hamito-Semitic) [Branches into Semitic, which includes Arabic proper, Hebrew, Ethiopic and Aramaic, and Berber (in the Atlas mountains), along with Cushitic, Egyptian (Coptic) and Chadic (Hausa); it is the language family with the oldest linguistic records].

SUBSAHARAN AFRICA 1) Niger-Congo (a very large group, grouping into Western Sudanic, with the branches Mande, West Atlantic, Gur and Kwa, and Benue-Congo of which the main branch is Bantu with over 500 languages stretching down to South Africa, includes Xhosa, Zulu and Kiswahili). 2) Nilo-Saharan (a diverse group stretching across the Sahara to Sudan).

SOUTH AFRICA 1) Khoisan (Bushman, Hottentot and other minor indigenous languages of the South African peninsula, noted for the presence of clicks).

SOUTH ASIA (Indian subcontinent, Pakistan) 1) Dravidian (Telugu, Tamil, Kannada; the second most important family in India). 2) Munda (consists of a number of languages spoken on the east coast of India). The remaining languages are Indo-European.

SOUTH-EAST, EAST ASIA 1) Sino-Tibetan (divides into at least three sub-groups: Sinitic, the chief representative of which are the dialects/languages of Chinese, Tibeto-Burman including Burmese and Tibetan, Tai which contains the two major languages Thai and Lao). 2) Mon-Khmer (Khmer spoken in Cambodia). 5) Independent. There are a number of independent languages in South and South-East Asia: Burushaski in Kashmir (northern India) is spoken by approximately 30,000. The language Ainu is spoken by even fewer speakers on various islands in northern Japan. Apart from these cases there are the three national languages: Vietnamese, Japanese and Korean. A possible link exists between the latter two, but it is tenuous and contested.

AUSTRALIA AND OCEANIA 1) Austronesian (Indonesian, Polynesian; consists of hundreds of island languages spread throughout a large area in the West Pacific). 2) Papuan (a group in a small area [that of the state of Papua, one half of the island state of Papua New Guinea]; it contains very many different languages in a small area and is comparable in diversity with the Caucasus). 3) Australian (the indigenous language family of Australia, consists of many languages spoken in all by not more than 50,000 aborigines).

THE AMERICAS Very many languages in many families are spoken by the native Americans of both continents. Among the major North American families (Canada, United States, Mexico) are: Algonkian, Wakashan, Salishan, Athapascan, Penutian, Yuman, Iroquoian, Siouan, Muskogean, Uto-Aztecan, Oto-Maguean, Zoquean, Mayan. The major families of Central-South America are: Macro-Chibchan, Ge-Pano-Carib and Andean Equatorial. Some of these languages, such as Quechua [Andean Equatorial], are spoken over a very large area (in Chile, Peru, Bolivia, Columbia and Ecuador) while Guaraní (in Paraguay) has official status alongside Spanish.

The Indo-European family

The proto-language of Indo-European probably originated in the area of present-day Ukraine / Southern Russia and was spoken up until about 3000 BC. From this area the speakers of this language spread out in various directions, eventually yielding separate dialects, the inputs to major subdivisions of the Indo-European family. Various features (most phonological) are used to distinguish these early divisions of the proto-language, such as the treatment of original [k] which was either shifted to [s] or preserved as [k]. Languages classified along this axis are said to be either centum languages (from the initial [k] in the Latin word for 100) or satem (from the initial [s] in the corresponding word in Avestan, an Indo-Iranian language).

Individual groups of Indo-European

INDO-IRANIAN This consists of the languages in and around Iran and of those groups who spread into north-west India and later throughout the whole country. Hindi and Urdu (the latter a close relative in Pakistan) are the main languages of the Indic branch whose classical form is Sanskrit.

ANATOLIAN An extinct group consisting in the main of Hittite, the language of the Hittite Empire (1700-1200 BC). Tablets containing remains of this language were discovered and identified in Turkey in the early twentieth century.

ARMENIAN A branch available from the ninth century AD in a Bible translation. It has continued as East Armenian (in the republic of Armenia) and West Armenian in Eastern Turkey.

TOKHARIAN Remnants of this language (an A and B version) were discovered by a German expedition at the beginning of the twentieth century in western China. It died out towards the end of the first millennium.

HELLENIC (GREEK) The set of dialects known as Classical Greek belong to this branch. Almost unbroken records are available covering over 2500 years. It continues as modern Greek.

ALBANIAN Despite its small numbers, Albanian represents a separate branch of the Indo-European family. First records are available from the 15th century.

ITALIC The term ‘Italic’ is used for those dialects of ancient Italy which include Latin but also Oscan and Umbrian (which strictly speaking form a separate branch). It continues as the set of Romance languages.

CELTIC Once spoken over a wide area in central Europe, the Celtic languages were pressed further west by rival Indo-European peoples which began to fill central and western Europe (Germanic tribes and Romans). It continues as the languages of the Celtic fringe of the British Isles and Breton in French Brittany.

GERMANIC This branch probably originated in southern Scandinavia and spread out from there to cover the area of present-day Germany, the regions to the south (Austria and Switzerland), the North Sea coast, England and the entire Scandinavian peninsula along with the Faroes and Iceland.

BALTIC A branch of its own with three representatives Lithuanian, Lettish and Old Prussian. The last language has been extinct since the 18th century. Present-day Lithuanian is particularly archaic and of special interest to Indo-Europeanists.

SLAVIC The oldest written form of Slavic is Old Church Slavonic. Nowadays there are three main branches: 1) Southern Slavic (Slovene, Croatian, Serbian, Macedonian, Bulgarian), 2) Western Slavic (Polish, Sorbian, Wendish, Czech, Slovak) and 3) Eastern Slavic (Russian, White Russian, Ukrainian).

Source: www.uni-due.de

2014-09-04

2014-09-04 3589

3589