Императорские пасхальные яйца

1) The Coronation Egg

THE CORONATION EGG: A FABERGÉ IMPERIAL EASTER EGG PRESENTED BY EMPEROR NICHOLAS II TO HIS WIFE, EMPRESS ALEXANDRA FEODOROVNA, AT EASTER 1897,WORKMASTER MICHAEL PERCHIN, ST. PETERSBURG

Enameled translucent lime yellow over a jeweled 8 e sunburst ground and applied with a green gold trellis of laurel leaf pinned at the top of the egg with a circle of diamonds and with black enamel Imperial eagles at the intersections, the shields of the eagles set with diamonds and the ribbons enameled blue, the top of the egg with the Imperial monogram of the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna set with diamonds and rubies on a white enamel ground beneath a table diamond, the bottom of the egg with a calyx of finely engraved leaves centered by the blackenameled date 1897 on a white enamel ground below a table diamond within a diamond-set circular frame. The egg opens to reveal a velvet-lined compartment containing a gold, platinum, enamel and jeweled miniature coach, a replica of Catherine the Great’s coach of 1793 which was employed in the coronation procession of Nicholas and Alexandra, executed in minute detail, enameled translucent strawberry red and applied with a diamond-set gold trellis, the roof mounted with gold Imperial eagles at the corners and sides and with a diamond-set Imperial crown at the center, the doors mounted with diamond-set Imperial eagles and with rock crystal windows engraved with drapery, the interior with tiny steps which fold down when the doors are opened, and with a translucent strawberry red enameled bench and cushions before a light blue enameled drapery with gold trim, the ceiling painted with gold vine and with a light blue enamel roundel within a gold wreath, a gold hook at the center, all components of the carriage finely articulated, the compartment itself suspended from gold springs, the gold wheels with platinum tires, the inner edge of the top of the egg marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster and pre-1899 assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold, the underside of the coach also marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster, pre-1899 assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold and Fabergé in Cyrillic; the name of Wigström scratched on the inner surface of the shell.

Enameled translucent lime yellow over a jeweled 8 e sunburst ground and applied with a green gold trellis of laurel leaf pinned at the top of the egg with a circle of diamonds and with black enamel Imperial eagles at the intersections, the shields of the eagles set with diamonds and the ribbons enameled blue, the top of the egg with the Imperial monogram of the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna set with diamonds and rubies on a white enamel ground beneath a table diamond, the bottom of the egg with a calyx of finely engraved leaves centered by the blackenameled date 1897 on a white enamel ground below a table diamond within a diamond-set circular frame. The egg opens to reveal a velvet-lined compartment containing a gold, platinum, enamel and jeweled miniature coach, a replica of Catherine the Great’s coach of 1793 which was employed in the coronation procession of Nicholas and Alexandra, executed in minute detail, enameled translucent strawberry red and applied with a diamond-set gold trellis, the roof mounted with gold Imperial eagles at the corners and sides and with a diamond-set Imperial crown at the center, the doors mounted with diamond-set Imperial eagles and with rock crystal windows engraved with drapery, the interior with tiny steps which fold down when the doors are opened, and with a translucent strawberry red enameled bench and cushions before a light blue enameled drapery with gold trim, the ceiling painted with gold vine and with a light blue enamel roundel within a gold wreath, a gold hook at the center, all components of the carriage finely articulated, the compartment itself suspended from gold springs, the gold wheels with platinum tires, the inner edge of the top of the egg marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster and pre-1899 assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold, the underside of the coach also marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster, pre-1899 assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold and Fabergé in Cyrillic; the name of Wigström scratched on the inner surface of the shell.

The 1897 Coronation Egg is the most celebrated and best known of all of Fabergé’s creations, the most exhibited and most published work of art by the Russian master. 2 As its name denotes, it commemorates the festivities surrounding the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna, which began with their entry into Moscow on May 9, 1896. Nicholas noted in his diary: “9 May. The first hard day for us – the day of our entrance into Moscow. By 12 an entire gang of princes had gathered, with whom we sat down to lunch. At 2.30 the procession began to move. I was riding on Norma, Mama was sitting in the first gold carriage and Alix in the second, also alone.” 3 At the head of the four-mile-long cortège, from the Petrovsky Palace outside the gates of Moscow to the Nicholsky Gate of the Kremlin, rode squadrons of the Imperial Guard, followed by the Cossacks of the Guard, Moscow’s nobility, then, on foot, the Court orchestra, the Imperial Hunt and court footmen. Nicholas rode on his white steed, simply dressed in a white army tunic, reigns in his left hand, right hand raised to his visor in salute. Behind Nicholas rode the Russian Grand Dukes and European nobility. Next came the widowed Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna in the massive carriage of Catherine the Great – Russian Court Protocol gave her precedence over the new Empress, a situation which was later to cause considerable friction between the two (the Dowager made good use of her right to wear the Russian Crown Jewels). Last came the young Empress dressed in dazzling white in a gilded coach drawn by eight white horses. According to the perhaps biased Princess Radziwil, the cortège was not a great success:

“When he made his entrance into Moscow, the golden carriages, magnificence, escort of chamberlains in gold-embroidered costumes, and soldiers in parade uniforms were the same as at his father’s coronation. But one could sense no genuine warmth in the tribute of the crowd, no enthusiasms other than that always found on such an occasion. Yes, the only time that the hurrahs of the masses seemed to come from the heart was when the Dowager Empress’ carriage appeared, while her daughter in law was met with deathly silence.” 4

On May 14, the Coronation took place in the Dormition, or Uspensky, Cathedral, a ceremony lasting four hours. Nicholas was seated on the throne of Tsar Mikhail Feodorovich inset with 870 diamonds, rubies and pearls. Alexandra Feodorovna sat on Ivan the Great’s Ivory Throne. Nicholas wore the uniform of the Preobrazhensky Guard, a heavy gold-thread mantle embroidered with black double-headed eagles and the nine-pound diamond crown of Catherine the Great, made by Jérémie Pauzie in 1762 (now in Diamond Fund of the Russian Federation, Moscow). Alexandra wore a silver-white court dress with a train carried by 12 attendants, a single strand of pink pearls and the small diamond crown (now in the collection of the Hillwood Museum, Washington, D.C.). Nicholas pondered the day’s events in his diary: “14 May, 1896. A great day, a triumphant day, but for Alix, Mama and me, difficult in the moral sense. I shall not forget it my whole life long.” 5

The Empress’ brother, Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hesse, who attended the Coronation ceremonies, described the scene vividly: “The coronation in Moscow on May 26th 1896 was the most opulent celebration which I ever witnessed. It bordered close to the Oriental and lasted for 10 days. In Moscow the cathedral was filled with paintings on gold ground of saints and all priests were dressed in gold robes applied with embroidery and precious stones. A very deep feeling of mysticism was in all the ceremonies and you could feel the tradition of Byzance. Through the holy oil the Emperor and the Empress are now sanctified (geheiligt.) The Emperor takes the Holy Communion as a priest in the inner sanctuary, then the Emperor takes his crown off before the throne, he kneels down and prays aloud the so wonderful prayer for his people. And following the prayer for the Emperor he gets up and then is the only person standing at that moment in the whole Russian Empire. The procession to and from the cathedral leads over an elevated passage, as high as the heads of the people around, so that all, who take part in the procession, can be seen. The procession is all uniforms, gold, silver, Emperor and Empress in their gold and ermine under a gigantic canopy, all grand duchesses (Fürstinnen) strewn with jewels. To look at all this must have been like a fantastic dream because the sun was shining an all.” 6

The Coronation Egg contains a faithful replica of the coach in which Alexandra rode. The egg’s shell, embellished with a trellis of black double-headed eagles on yellow 10 eweled 10 e enamel ground, is a reminder of the heavy cloaks of gold thread in woven with Imperial eagles by the Moscow firm of Sapozhnikov, that were worn by the Imperial couple at the coronation ceremony in the Uspensky Cathedral, a scene perfectly rendered in Laurits Tuxen’s paintings.

Alexandra Feodorovna’s carriage was a 10 ewel coach built in St. Petersburg by Johann K. Buckendahl in 1793. The original, 512 cm long and 270 cm high, is made of oak, ash, birch, lime, iron and steel and is embellished with copper, brass, bronze, silver and gold, its interior is decorated with velvet and silk, with beveled glass windows. It is suspended on four C-shaped transverse springs and sits length- and cross-wise on straps, has seats for the coachman and pages, rear steps for the footmen and folding steps attached to the floor of the carriage. The exterior is upholstered with dark red velvet, applied with sequins, artificial diamonds, tassels and golden embroidery of trelliswork, flowers and foliage. The coach is surmounted by a copper-gilt crown set with pastes (originally aquamarines). The coach was renovated in 1826, 1856, 1894 and 1896 and most recently in 1992-93 through a grant of the Ford Motor Company for a Fabergé exhibition held at the Winter Palace in 1993, when it was carried up the Ambassador’s Staircase in pieces and then reassembled to be shown alongside the Fabergé miniature replica in St. George Hall. 7

In 1952 the goldsmith responsible for the Fabergé coach, Georges Stein, was still alive. Kenneth Snowman interviewed him and recorded Stein’s remembrances in his 1953 publication. 8 Stein was aged twenty-three at the time when Fabergé hired him away from the jeweler Kortman, offering him a higher salary of five rubles a day ($2.50). His eyesight is said to have been so incredibly good that he could detect a flaw in a diamond without a loupe. The meticulous work on the coach, executed without any artificial optic aid, took fifteen months at sixteen hours a day – a total of 7,200 hours – with many a visit to the Imperial Coach Museum. The cost to Fabergé of the coach alone would, according to Stein, have been 2,250 rubles, exactly half of what Fabergé charged the Tsar for the egg. A pear-shaped emerald drop suspended in the coach’s interior cost an extra 1,500 rubles; the glass case in which the coach was separately exhibited, an additional 150 roubles.

The Coronation Egg was displayed in the Empress’ apartment in the Winter Palace in a corner cabinet and is exactly described in 1909 by N. Dementiev, Inspector General of the Imperial Winter Palace, including its white velvet-lined interior which was the “ nest for the model State carriage.... The egg rests on a silver-gilt wire stand. ” 9 The surprise and its separate glass case were also minutely described, including “ a yellow diamond pendant egg (briolette)” which hung in the carriage (and which apparently had replaced the original emerald drop). “It is placed on a rectangular jadeite pediment with a silver-gilt rim and is contained in a rectangular glass case with silver-gilt edging. Silver-gilt Imperial crowns are placed at each of the four corners of the case.” 10

The egg was confiscated by the Provisional Government in 1917, listed among the treasures removed from the Anichkov Palace, dispatched to the Kremlin and finally transferred to the Sovnarkom in 1922 for sale: “

1 gold egg with diamonds and rose-cut diamonds, containing a gold carriage with a pear-shaped diamond.” 11

The egg was sold by Antikvariat to dealer Emanuel Snowman in 1927, sold by his London firm Wartski to Charles Parsons in 1934, reacquired by Wartski in 1945 and sold, together with the Lilies of the Valley Egg, to Malcolm Forbes for a total of $2,160,00 in 1979.

2) The Lilies of the Valley Egg

THE LILIES OF THE VALLEY EGG: A FABERGÉ IMPERIAL EASTER EGG PRESENTED BY EMPEROR NICHOLAS II TO

HIS WIFE THE EMPRESS ALEXANDRA FEODOROVNA AT EASTER 1898,WORKMASTER MICHAEL PERCHIN,

ST. PETERSBURG

The egg enameled translucent rose pink over a 11 eweled 11 e ground and surmounted by a diamond and ruby-set Imperial crown, the egg divided into four quadrants by diamond-set borders, each quadrant with climbing gold sprays of lily of the valley, the flowers formed by diamond-petaled pearls, the finely sculpted gold leaves enameled translucent green and rising from curved legs formed of wrapped gold leaves set with diamonds ending in scroll feet topped with pearls, a pearl-set knob at the side of the egg activates a mechanism which causes the crown to rise revealing a fan of three diamond-framed portrait miniatures of Tsar Nicholas II and the children of Nicholas and Alexandra, Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana, each signed by the miniaturist Johannes Zehngraf, the reeded gold backs of the miniatures engraved with the date 5.IV.1898, marked on these backplates with Cyrillic initials of workmaster, Fabergé in Cyrillic and assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold.

The egg enameled translucent rose pink over a 11 eweled 11 e ground and surmounted by a diamond and ruby-set Imperial crown, the egg divided into four quadrants by diamond-set borders, each quadrant with climbing gold sprays of lily of the valley, the flowers formed by diamond-petaled pearls, the finely sculpted gold leaves enameled translucent green and rising from curved legs formed of wrapped gold leaves set with diamonds ending in scroll feet topped with pearls, a pearl-set knob at the side of the egg activates a mechanism which causes the crown to rise revealing a fan of three diamond-framed portrait miniatures of Tsar Nicholas II and the children of Nicholas and Alexandra, Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana, each signed by the miniaturist Johannes Zehngraf, the reeded gold backs of the miniatures engraved with the date 5.IV.1898, marked on these backplates with Cyrillic initials of workmaster, Fabergé in Cyrillic and assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold.

Fabergé’s invoice lists this egg as:

“April 10. Pink enamel egg with three portraits, green enamel leaves, lilies of the valley pearls with rose-cut diamonds. St. Petersburg, May 7, 1898 6700r.” 1

The Lilies of the Valley Egg is adorned with the favorite flowers and the favorite jewels – pearls and diamonds – of the young Empress. It also contains, as its surprise, miniatures of her three favorite people in the world: her adored husband Nicholas and her two daughters, Olga (born 1895) and Tatiana (born 1897). Moreover, Fabergé designed the egg in the Tsarina’s favorite style – Art Nouveau. Doubtless this egg was also one of her favorite objects by the Russian master.

For a brief period of approximately five years, Fabergé championed the cause of Art Nouveau in Russia. The present egg of 1898 marks the initial appearance of this style in his oeuvre while the Clover Egg of 1902 (Kremlin Amory Museum, Moscow) 2 is the last dateable example in this idiom created in St. Petersburg for the Imperial family. The Russian equivalent to French Art Nouveau and German Jugendstil was Stil Moderne and Mir Iskusstva or the World of Art Movement. 3 The driving force behind Mir Iskusstva was Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929). In 1885 the art patron Savva Mamontov founded a private opera house in Moscow and an artists’ colony at Abramtsevo, where a group of artists including Ilya Repin, Vassilii Polenov and Victor Vasnetsov, together with younger artists such as Konstantin Korovin, Valentin Serov and Mikhail Vrubel, developed new ideas which stood in stark contrast to the established art of the Peredvizhniki, or Wanderers. The dynamic Diaghilev, with the aid of St. Petersburg artists such as Léon Bakst, Alexander Benois and Evgeny Lanceray and the financial backing of Savva Mamontov and Princess Maria Tenisheva, published the group’s journal, World of Art, which appeared for six years between 1899 and 1904. A first exhibition of the group’s art took place in 1898; a second pioneering exhibition was held at the Stieglitz Museum in early 1899 with participation of such foreign artists as Böcklin, Boldini, Degas, Liebermann, Monet and Renoir and such craftsmen as Lalique, Tiffany and Gallé. Fabergé’s interest in this style dovetails neatly with Mir Iskusstva’ s existence.

The Lilies of the Valley Egg was displayed at the 1900 World Fair, which marked the peak of Parisian excitement over Art Nouveau. René Lalique’s stand at the fair with its bronze storefront of winged female figures engendered a furor amongst his numerous followers. He was awarded a Grand Prix and the Order of the Legion of Honor or his creations. The same jury which lauded Lalique’s work to the heavens was curiously ambivalent about Fabergé’s Art Nouveau submissions. The floral decoration of this egg was described as “ of delicate taste ” but criticized as “too closely adhering to the egg.” The critic would have preferred “three feet instead of four, leaves not terminated by banal scrolls and that the egg should have been set with asymmetrical sprays.” 4 But then the critic also found fault with another of Fabergé masterpieces, the Lilies of the Valley Basket (now in the Matilda Geddings Gray Foundation Collection, Fine Arts Museum, New Orleans), which was viewed by him as “without artistic or decorative feeling. We have before us a photograph of nature without the artist having impressed his own style upon it.” 4

Alexandra Feodorovna’s interest in Art Nouveau is well documented. Her brother, Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hesse, founded a colony of artists on the Mathildenhöhe in Darmstadt, where they endeavored to create joint works of art or Gesamtkunstwerke of interior design, furniture and pottery. Inspired by this artistic climate, she collected pieces of Gallé and Tiffany glass, Roerstrand and Doulton pottery, many of which were mounted for her by Fabergé’s specialist silversmith, Julius Rappoport. 5 These works stood on cornices and mantelpieces in her salons at the Alexander Palace, interspersed with Victorian clutter of sentimental character.

The present egg was kept by the Empress in her private apartment in the Winter Palace on the first shelf from the top of a corner cabinet and is described in detail by N. Dementiev, Inspector of Premises of the Imperial Winter Palace, in 1909, including its mechanism (“At the side of the egg there is a button with a single pearl which, when pressed causes the crown to rise and disclose three miniature medallions framed in rose-cut diamonds”). 6

The Lilies of Valley Egg is clearly visible in a pyramidal showcase, together with other eggs from the collection of Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna, at the 1902 von Dervis mansion exhibition (p. 186). It is also mentioned in a description of the exhibition, albeit confused with the Lilies of Valley Basket, which stood next to it: “The Empress Alexandra Feodorovna’s collection contains an egg containing a bouquet of lilies of the valley surrounded by moss: the flowers are made of pearls, the leaves of nephrite, and the moss of finest gold.” 7

The Lilies of the Valley Egg was one of nine eggs sold by Antikvariat to Emanuel Snowman of Wartski around 1927. Like the Coronation Egg, it too was then sold to Charles Parson in 1934 and bought back by Wartski. It was then sold by Wartski to Mr. Hirst and bought back yet again. In 1979 Kenneth Snowman of Wartski sold the egg to Malcolm Forbes together with the Coronation Egg for a total of $2,160,000.

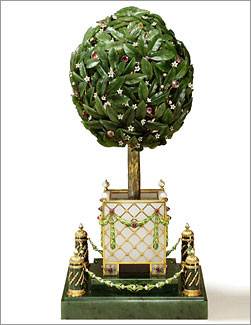

2. The Orange Tree (Bay Tree) Egg

THE BAY TREE EGG: A FABERGÉ IMPERIAL EASTER EGG PRESENTED BY EMPEROR NICHOLAS II TO HIS MOTHER THE DOWAGER EMPRESS MARIA FEODOROVNA AT EASTER 1911

The topiary tree formed as a profusion of carved nephrite, finely veined leaves and jeweled fruit and flowers on an intricate framework of branches, the fruit formed by champagne diamonds, amethysts, pale rubies and citrines, the flowers enameled white and set with diamonds, a keyhole and a tiny lever, hidden among the leaves, when activated open the hinged circular top of the tree and a feathered songbird rises, flaps its wings, turns its head, opens its beak and sings, the gold trunk chased to imitate bark and planted in gold soil is contained in a white quartz tub applied with a gold trellis chased with flowerheads at the intersections and further applied with swags of berried laurel enameled translucent green and pinned by cabochon rubies, the central rubies edged by diamonds, each foot of the tub also applied with chased gold rosettes set with cabochon rubies and diamonds, the corners of the tub with pearl finials, the square carved nephrite base in two steps with a miniature nephrite fluted column at each corner set with chased gold mounts, each column with a reeded gold cap surmounted by a pearl nestled in translucent green enamel leaves, the swinging gold chains between the columns formed as pearl flowers with translucent green enamel leaves, inscribed Fabergé in Cyrillic with the date 1911 on lower front rail of the tub.

The topiary tree formed as a profusion of carved nephrite, finely veined leaves and jeweled fruit and flowers on an intricate framework of branches, the fruit formed by champagne diamonds, amethysts, pale rubies and citrines, the flowers enameled white and set with diamonds, a keyhole and a tiny lever, hidden among the leaves, when activated open the hinged circular top of the tree and a feathered songbird rises, flaps its wings, turns its head, opens its beak and sings, the gold trunk chased to imitate bark and planted in gold soil is contained in a white quartz tub applied with a gold trellis chased with flowerheads at the intersections and further applied with swags of berried laurel enameled translucent green and pinned by cabochon rubies, the central rubies edged by diamonds, each foot of the tub also applied with chased gold rosettes set with cabochon rubies and diamonds, the corners of the tub with pearl finials, the square carved nephrite base in two steps with a miniature nephrite fluted column at each corner set with chased gold mounts, each column with a reeded gold cap surmounted by a pearl nestled in translucent green enamel leaves, the swinging gold chains between the columns formed as pearl flowers with translucent green enamel leaves, inscribed Fabergé in Cyrillic with the date 1911 on lower front rail of the tub.

First known in 1935 as a Bay Tree Egg, this egg which had since 1947 been incorrectly labeled as an Orange Tree, was given by Tsar Nicholas to his mother the Dowager Empress on April 12, 1911. It has recently been correctly identified as a bay tree, based on the original Fabergé invoice:

“9 April. 1 large egg shaped as a gold bay tree with 325 nephrite leaves, 110 opalescent white enamel small flowers, 25 diamonds, 20 rubies, 53 pearls, 219 rose-cut diamonds, 1 large rose-cut diamond. Inside the tree is a mechanical song-bird. [It stands] in a rectangular tub of white Mexican onyx on a nephrite base, with 4 nephrite columns at the corners suspending green enamel swags with pearls St. Petersburg, June 13, 1911. 12,800 rubles.” 1

In addition, it is identified as a bay tree when catalogued among the items removed from the Anichkov Palace of the Dowager Empress to the Kremlin Armory (“ Nephrite bay tree on base, gold mounted with varicolored precious stones and with song bird”) 2 and again among the treasures transferred to Sovnarkom in 1922 (“ 1 nephrite tree with singing bird, gold ornaments, rose-cut diamonds, topazes, pearls and rubies”). 3

The model for the Bay Tree Egg is an eighteenth-century singing-bird tree of which numerous examples are recorded. A similar mechanical singing-bird tree was sold by Sotheby’s at the Mentmore Tower Sale, May 18, 1977, lot 49 (ill. On p. 218). Singing-bird trees were apparently already known in the sixteenth century. Agostino Ramelli 4 illustrates a vase with a singing-bird tree, which he describes as “ une sorte de vase qui donnera grand plaisir et contentement à toute personne qui se délectera de voir entendre les sifflets etc..” This model was driven by air, the birds beat their wings and opened their beaks, while their song was imitated on flutes. In 1709, an automaton was described in Basel, Switzerland, as “ un arbre 14 eweled 14 e 14 où il est représenté dans cet arbre 24 oiseaux de diférante spèce avec un coq et une poule chantant chacun leur chant 14 eweled 14 e comme s’il estoit naturel. ” 5

Interestingly, there is also a parallel in contemporary architecture, the cupola of the Vienna Secession Exhibition Hall, built by Joseph Maria Olbrich in 1897-98, which shows a related foliate openwork dome (see ill. Below). Fabergé’s connection to the Viennese Secession and to the Wiener Werkstätte, founded in 1903, need yet to be analyzed. There seems to be no doubt that the sparse geometric forms of Joseph Hoffman made their mark on the late oeuvre of the Russian master.

The egg was confiscated by the Provisional Government in 1917 and transferred from the Anichkov Palace to the Kremlin. It was one of nine eggs sold by Antikvariat to Emanuel Snowman ofWartski around 1927. It has since passed through the hands of five different owners and was sold by Mrs.Mildred Kaplan to Malcolm Forbes in 1965 for $35,000.

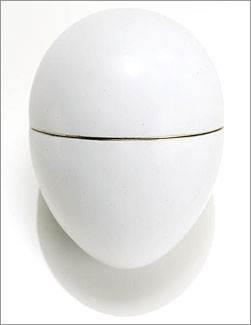

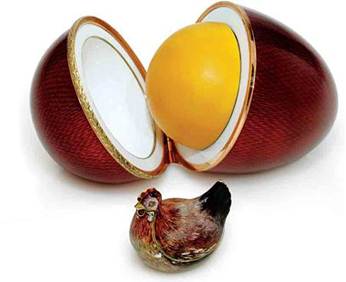

4) The Hen Egg: The First Imperial Egg

THE HEN EGG (THE FIRST IMPERIAL EGG): A FABERGÉ IMPERIAL EASTER EGG PRESENTED BY EMPEROR ALEXANDER III TO HIS WIFE THE EMPRESS MARIA FEODOROVNA AT EASTER 1885

The white enameled egg simulating eggshell, opening by means of three bayonet fittings to reveal a matted gold “yolk” which in turn opens by similar means to reveal a varicolor gold hen in a suede-lined nest with stippled gold edge simulating straw, the hen’s yellow and white gold feathers, yellow gold head and red gold comb and wattle all meticulously chased, the eyes set with cabochon rubies, the body of the hen opening by means of a concealed hinge at the tail, the underside of the body finely chased with yellow gold feet, unmarked.

The Hen Egg is the first of the legendary series of fifty 1 Imperial Easter Eggs created by Fabergé for the last two tsars of Russia between 1885 and 1916. It is unmarked, but, following the opening of the Russian archives and the discovery of the present egg listed as the first among the five earliest Imperial Easter eggs, 2 together with an exchange of letters between Tsar Alexander III and his brother Vladimir referring to this egg, all possible doubts have been dispelled as to its exact nature. 3

On February 1, 1885, Alexander wrote a letter to his brother referring to an order from Fabergé:

“...this could be very nice indeed. I would suggest replacing the last present by a small pendant egg of some precious stone. Please speak to Fabergé about this, I would be very grateful to you… Sasha.” 4

Grand Duke Vladimir sent the finished egg to the Tsar together with a letter on March 21, 1885 saying that the egg being made according to his wishes by the jeweler Fabergé was in his opinion a complete success and of fine and intricate workmanship. In accordance with his wishes the ring was replaced by an expensive specimen ruby pendant egg on a chain, which Empress Maria Feodorovna could wear as a “symbol of autocracy.” Grand Duke Vladimir attached a set of instructions for the Tsar on how to open the hen surprise, warning him of its fragility.

The Emperor replied from Gatchina the same day that he was very grateful to his uncle Vladimir for the trouble that he taken in placing the order with Fabergé and for having overseen its production. He was very satisfied with the workmanship, which was truly exquisite. He appreciated his uncle’s instructions for opening the surprise and hoped that the egg would have “the desired effect on its future owner.” 5

Fabergé’s egg was to be a replica, or a free rendering, of an early eighteenth-century egg, of which at least three examples are still in existence (Rosenborg Castle, Copenhagen; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; Private Collection, formerly in the Green Vaults, Dresden). 6 They all have in common a hen surprise, opening to reveal a crown in which is contained a ring. It is generally assumed that the Tsar wished to surprise his wife with a souvenir inspired by an item well known to her in the Danish royal treasury. Fabergé is known to have relished the challenge of measuring his work against that of an eighteenth-century master.Of these three eggs, the Dresden Hen Egg would have been familiar to Fabergé, who lived in the Saxon capital as a young man, and whose parents from 1860 onwards resided in that city and died there.

Fabergé’s original crown and two ruby surprises are listed in Fabergé’s invoice of 1885 and in a description of 1889, but were no longer part of the egg by 1917. The two ruby eggs al one priced at 2,700 rubles accounted for more than half of the total price of 4,151 rubles. A related lapis lazuli hen egg in the Cleveland Museum of Art from the collection of India Early Minshall, possibly a variation on the theme by Fabergé, still retains a ruby pendant suspended within the crown.7 A further unmarked “Egg-and-hen egg” from the collection of King Farouk of Egypt was acquired by Matilda Geddings Gray from Armand Hammer in 1957, when it was thought to be the First Imperial Egg. 8

The Hen Egg is listed in the account books of the Assistant Manager of His Majesty’s Cabinet, N. Petrov, as:

“White enamel Easter egg, with a crown, set with rubies, diamonds and rose-cut diamonds (and 2 ruby pendant eggs – 2700 rubles) – 4151 rubles” 9 followed by another entry:

“9 April (1885) To the jeweler Fabergé for a gold egg with precious stones, 4151 rub. 75 kop. 11 April. Allocation No. 337.” 10

In a list of eggs established in 1889, N. Petrov lists the present egg as the first, dated 1885.

With the exception of the Kelch First Egg and the Scandinavian Egg, none of the hen eggs bear the hallmark of the maker. The present egg’s date falls into the first year of Michael Perchin’s activity.Habsburg, 11 who dates Perchin’s arrival at Fabergé to 1884 based on the year inscribed on the Bismarck Box, believes the Hen Egg to be by Perchin. Ulla Tillander, 12 who dates Perchin’s arrival to 1886, thinks that the egg belongs to the oeuvre of Erik Kollin. The hen-in-the-egg theme containing a crown found many emulators in the nineteenth century. A number of jeweled versions made in Vienna or Hungary are known.

It is generally thought that Tsar Alexander III commissioned this First Egg as a souvenir of home for Alexandra Feodorovna – a token of affection for his homesick wife, who would have known the Danish original in her family’s collection. As a convert to the Orthodox Church, she was well aware of the importance of the egg in Russia as a symbol of the Resurrection of Christ. The tradition of presenting simple painted eggs, generally red, together with an exchange of three kisses and the greeting “Christ is Risen!” (to which the response was “Indeed He is Risen!”) harks back to the Middle Ages. 13 As time went on, eggs became more and more lavish, with elaborately painted duck and goose eggs and with papier-mâché, wood and lacquer eggs supplanting the hen eggs. In the later eighteenth century, after the founding of the Imperial Porcelain Manufacture and of the Imperial Glass Manufacture under Catherine the Great, the Tsarina and the Tsar presented ever-growing numbers of eggs in these rarer materials. The number of such eggs presented at court grew to 5,000 in porcelain and 7,000 in glass by the mid-nineteenth century. By Imperial decree, Tsar Alexander III reduced these numbers, allowing no more than a total of 120 eggs to be presented. During the reign of Tsar Alexander III and Tsarina Maria Feodorovna, the first porcelain eggs with gold 17eweled on a white or sang de boeuf ground made their appearance.

The earliest known example of an Imperial Easter egg is a jeweled, gold, egg-shaped necessaire fitted with a clock, Paris 1757-58, owned by Empress Elisabeth I and bearing her monogram 14 which served as model for Fabergé’s Peter the Great Egg of 1903, now in Richmond, Virginia. Several examples date from the reign of her successor, Empress Catherine the Great, for example an egg-shaped enameled gold brûle parfum, said by tradition to have been given to the Empress by her lover, Prince Grigory Potemkin. It is now in the treasury of the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, and was no doubt well known to Fabergé. 15

A diamond-set egg-shaped charm containing a tiny miniature of the Empress is in the same collection and may have inspired Fabergé’s vast number of miniature Easter eggs.16 A set of four cups and covers made of gold, enamel and ivory from the 1780s inspired Faber gé to create an egg decorated with gold lilies of the valley. 17

The First Egg was confiscated by the Provisional Government and sold to a Mr. Derek. It then appeared at an auction at Christie’s in London, March 15, 1934, lot 55, consigned by a Mr. Frederick Berry. It was catalogued as the egg presented by Alexander III in 1888 (sic) and sold for £85 (reserved at 50 guineas) to R. Suenson-Taylor (later created Lord Grantchester), with a Mr. Sassoon as underbidder.

5) The Rosebud Egg

THE ROSEBUD EGG: A FABERGÉ IMPERIAL EASTER EGG PRESENTEDBY EMPEROR NICHOLAS II TO HIS WIFE THE EMPRESS ALEXANDRA FEODOROVNA AT EASTER 1895,WORKMASTER MICHAEL PERCHIN, ST. PETERSBURG

Enameled translucent strawberry red over a 18 eweled 18 e ground and divided into four vertical panels by diamond-set borders, each panel of the hinged top applied with green gold laurel wreaths tied with red gold and diamond-set ribbons, each panel of the lower portion of the egg applied with diamond-set arrows entwined by green gold laurel garlands tied with red gold ribbons and pinned by diamonds, the top of the egg mounted with a table diamond beneath which is set a portrait miniature of Tsar Nicholas II, the base of the egg enameled with the date 1895 below a diamond, the egg opening to reveal a velvet-lined interior fitted with a rosebud with hinged petals enameled yellow and with green enamel leaves, marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster, Fabergé in Cyrillic and assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold.

Enameled translucent strawberry red over a 18 eweled 18 e ground and divided into four vertical panels by diamond-set borders, each panel of the hinged top applied with green gold laurel wreaths tied with red gold and diamond-set ribbons, each panel of the lower portion of the egg applied with diamond-set arrows entwined by green gold laurel garlands tied with red gold ribbons and pinned by diamonds, the top of the egg mounted with a table diamond beneath which is set a portrait miniature of Tsar Nicholas II, the base of the egg enameled with the date 1895 below a diamond, the egg opening to reveal a velvet-lined interior fitted with a rosebud with hinged petals enameled yellow and with green enamel leaves, marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster, Fabergé in Cyrillic and assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold.

On October 20, 1894, Tsar Alexander died. Just a few weeks later, on November 14, his son married Nicholas Alexandra Feodorovna, formerly Princess Alix Victoria Helene Luise Beatrix of Hesse-Darmstadt. The homesick young bride missed, among other things, the roses in her homeland. In Darmstadt, there was a famous rose garden called “Rosenhöhe,” established in 1810 by Grand Duchess Wilhelmine of Hesse, Princess of Baden (1788-1836) and designed by the Swiss garden architect Zeyher. In 1894, Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig, Alexandra’s brother, built the Palais Rosenhöhe there (destroyed 1944) and had the garden redesigned, adding the Rosendom. To this day, the Rosenhöhe remains one of the most beautiful rose gardens in Germany. The Rosebud Egg, then,was an ideal gift for Nicholas to give to his adored wife for their first Easter together. 1

With its bonbonnière shape, its chased gold laurel swags, its diamond-set tied ribbons and arrows and its red 18 eweled 18 e enamel ground, the egg is a perfect rendition of an eighteenth-century symbol of Love. The Rosebud Egg is also the quintessence of Fabergé’s new Neo-Classical style. Neoclassicism, inspired by Antiquity, was developed during the reign of Louis XVI as a reaction against the exuberant Rococo idiom of the Louis XV period. As in the case of the eighteenth century, nineteenth century Neo-Classicism followed the Neo-Rococo of the 1880s and is best seen in Michael Perchin’s early work for the Fabergé firm. In Paris the new Neo-Classical style was embraced by those few who eschewed the all-powerful influence of Art Nouveau. The two contrasting styles of Neo-Classicism and of Art Nouveau are clearly represented in the oeuvre of the great firms of Cartier and Lalique. On one hand, Cartier, ensconced in the firm’s new rue de la Paix premises, did not exhibit at the 1900 Exposition Universelle and totally negated the much fêted symbolist movement. On the other hand stood the extraordinary series of jewels created by Lalique for Calouste Gulbenkian, shown to much public acclaim at the 1900 World Fair. The light touch and elegance of Cartier’s novel Neo-Classical style was underlined by the firm’s use of platinum, a Cartier innovation. Even contemporary music, such as Debussy’s Pelleas et Mélisande of 1900-1902, reflects the influence of Neo-Classicism.

The floral form of the surprise is an eighteenth-century concept continued into the nineteenth century. Such enameled flowers, popular at the time as watch-cases or perfume bottles, were generally produced in Geneva. A Swiss rose with spring-loaded pink enamel petals opening to show a watch was made in Geneva in the 1830s. 2 Fabergé’s yellow rose originally opened to reveal a crown containing a pear-shaped ruby pendant as further symbols of Imperial authority and of Love.

This egg is listed on Fabergé’s invoice as:

“31 March. Red enamel egg with crown. St. Petersburg,May 9, 1895 3250 r.” 3

The Rosebud Egg, the first Imperial Easter Egg received by the new Empress, was kept by her, along with all the early Fabergé Easter eggs, in a corner cabinet of the Imperial couple’s private apartment at the Winter Palace, between a door leading into the bedroom and a window. There the egg and its surprise were minutely described in 1909 by the Inspector of Premises of the Imperial Winter Palace as containing “ an Imperial crown entirely made of rose-cut diamonds with two cabochon rubies. ” 4

The Rosebud Egg was first exhibited in 1935 in London as owned by a Mr. Parsons, still containing its surprise of a diamond-set crown with a pendant ruby. In 1953 Kenneth Snowman included an archival photograph of it and listed its current whereabouts as unknown. Lost for four decades, rumor had it that the egg had been seriously damaged, if not destroyed, in a marital dispute. Telltale damage to the enamel (expertly repaired since) enabled Malcolm Forbes, who acquired the egg in 1985 from the Fine Art Society, London, to ascertain the egg’s authenticity

6) THE SPRING FLOWERS EGG

A FABERGÉ GOLD, PLATINUM, ENAMEL, HARDSTONE AND JEWELED EASTER EGG,WORKMASTER MICHAEL PERCHIN, ST. PETERSBURG, PRE- 1899

Enameled translucent strawberry red over a 19 eweled 19 e ground and applied with neorococo gold scrolls and foliage, opening along a vertical diamond-set seam to reveal a removable diamond-set platinum miniature basket of wood anemones, the flowers with chalcedony petals and demantoid pistils, the egg fastening at the top by means of a diamond-set clasp, the lobed bowenite base with a diamond-set girdle and with a gold rim pierced with neorococo shell work and scrolls, marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster, Fabergé in Cyrillic and assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold, also with scratched inventory number 44374 or possibly 44474.

Enameled translucent strawberry red over a 19 eweled 19 e ground and applied with neorococo gold scrolls and foliage, opening along a vertical diamond-set seam to reveal a removable diamond-set platinum miniature basket of wood anemones, the flowers with chalcedony petals and demantoid pistils, the egg fastening at the top by means of a diamond-set clasp, the lobed bowenite base with a diamond-set girdle and with a gold rim pierced with neorococo shell work and scrolls, marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster, Fabergé in Cyrillic and assay mark of 56 standard for 14 karat gold, also with scratched inventory number 44374 or possibly 44474.

The Spring Flowers Egg, hallmarked with head workmaster Michael Perchin’s “early” mark, is struck with the St. Petersburg’s assay mark for before 1899 and appears to bear a scratched number 443 (or 4) 74, which may or may not be Fabergé’s inventory number. Its original fitted case is stamped with Fabergé’s Imperial Warrant and the addresses of St. Petersburg, Moscow and London. These facts seem to be in apparent contradiction. The hallmark dates the egg to before 1899, the original case to after 1903, after the opening of the London Branch. Inventory numbers do not generally appear on Imperial eggs.

A list of objects dated 14-20 September 1917 transferred from the Dowager Empress’s Anichkov Palace to the Kremlin Armory and signed by Major-General Yerechov, 1 mentions a “purse of gilt silver in the form of an egg covered with red enamel, with a sapphire” and, separately, “a basket of flowers with diamonds,” which probably correspond to this egg and its surprise. It was sold by the State firm Antikvariat in charge of the disposals of Russian Imperial treasure, to an unspecified buyer in 1933 for 2,000 rubles ($1,000), later sold by A La Vieille Russie to the Long Island collector Lansdell Christie, and again by the same New York dealers to Malcolm Forbes as an Imperial egg in 1966. It was exhibited as an Imperial Easter egg twice at the Metropolitan Museum in 1961 and 1996 and at the seminal exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1977, and, up to 1993 has been published by all leading specialists, including Bainbridge (1949), Snowman (1962, 1963, 1964, 1972), Habsburg (1979, 1987, 1993, 1996), Solodkoff (1979, 1984, 1988, 1995) and Hill (1989) as part of the series of Imperial eggs. Recently, Muntian (1995) and Fabergé/Proler/Skurlov (1997) have excluded the Spring Flowers Egg from the list of presents made by the last two Tsars. Muntian, based on the 1917 inventory of the Anichkov Palace, now believes that it belonged to the Dowager Empress and assumes that it was presented to her by a relative or close friend.

With its decoration of scrolls and rocaille, the Spring Flowers Egg is a typical example of Michael Perchin’s early Neo-Rococo style, probably dating from the late 1880s or early 1890s. This date is borne out by the early form of Perchin’s initials. Inexplicably, the basket of wild anemonies in this early egg is virtually identical to the surprise contained in the Winter Egg designed by Alma Pihl for Albert Holmström in 1913.

7)  The Scandinavian Egg

The Scandinavian Egg

THE SCANDINAVIAN EGG: A FABERGÉ VARICOLOR GOLD AND TRANSLUCENT ENAMEL EASTER EGG,WORKMASTER MICHAEL PERCHIN, ST. PETERSBURG, 1899-1903

Enameled translucent strawberry red over a 21 eweled 21 e ground, bisected by a red gold band applied with a chased green gold border of laurel, the egg opening horizontally to reveal a white enamel interior resembling the white of an egg and a matte yellow enameled “yolk,” the yolk hinged and opening to reveal a suede fitted compartment holding a naturalistically enameled gold hen painted primarily in shades of brown with touches of gray and white, when lifted at the beak the hen opens horizontally, the hinge concealed in the tail feathers, marked with Cyrillic initials of workmaster and 56 standard for 14 karat gold, also with scratched inventory number 5356.

The present Easter egg is one of a series of hen-and-egg creations by Fabergé, of which a small number have survived. The nearest parallel is the more lavish Kelch Hen Egg (p. 288), which closely resembles the present example but for the fact that it lies on its side and is not embellished with diamonds. Both eggs are otherwise virtually identical with their red 21 eweled 21 e enamel exteriors, their opaque white enamel “whites,” their opaque yellow enamel “yolks” and their varicolored painted hens with rose-cut diamond eyes. Both are by Michael Perchin and date from between 1899 and 1903. Other naturally shaped Easter eggs include the First Hen Egg of 1885 (p. 74), the first of the Imperial series and two unmarked eggs, one of lapis lazuli containing a crown in its yolk (Cleveland Museum of Art) 1 and an egg with platinum shell, hen, crown and ring, attributed to Erik Kollin (Fine Arts Museum, New Orleans), 2 which is undoubtedly not Russian.

The present egg was discovered in an Oslo bank safe by the present author in 1980 among the effects of Maria Quisling (1900-1980), the widow of Vidkun Quisling (1887-1945). They lived in a mansion at Bygdøy in Olso, which he called Gimle after the Hall of Gimle, the most beautiful place on earth according to Norse mythology.

Vidkun Quisling was the son of Jon Quisling, a Lutheran priest and well-known genealogist. A major in the Norwegian army, Quisling served as Military Attaché in Petrograd in 1918-1919, where he probably acquired the present egg, and in Helsinki in 1919-1920. He later worked with Fridtjof Nansen in the Soviet Union during the famine in the 1930s. Quisling served as Minister of Defence in 1931-1933 and founded the fascist Norwegian Socialist party, the Nasjonal Samling, in 1933 together with State Attorney Johann Bernhard Hjort. He became the leader of this originally religiously rooted party, which became outspokenly pro-German and anti-Semitic from 1935 onward.When Hitler’s armies invaded Norway on April 9, 1940, Quisling supported the Führer’s new Reichskommissar Joseph Terboven and became Prime Minister in 1942. After the German surrender in 1945, he was tried as a traitor and executed by firing squad.

The origin of the hen-in-an-egg Easter present harks back to the beginning of the eighteenth century. Three very similar 22eweled eggs have survived, each formerly in a royal treasury. The best known, due to its traditional association with Fabergé’s First Hen Egg, is an egg in the Chronological Collection of the Queen of Denmark at Rosenborg Castle (p. 84), Copenhagen; another is in the Kunsthistorische Museum, Vienna, as part of the Habsburg Collections; yet another is listed among the treasures of the Grünes Gewölbe, the Green Vaults in the Castle of the Elector-Kings of Saxony (Private Collection, both illustrated on p. 84). All three have yolks containing hens, which open to reveal a crown within which nestles diamond-set ring. All three are thought to have originated in Paris, dating from the 1720s. 3 The theme remained popular throughout the nineteenth century.

As the present egg is not listed among the Imperial presents, it was probably privately commissioned in St. Petersburg.Other documented, privately owned eggs by Fabergé include the series of seven Kelch eggs, of which the 1898 Kelch Hen Egg (p. 288) was the first and the 1904 Kelch Chanticleer Egg (p. 306) the last; the Nobel Ice Egg 4 circa 1914; the 1902 Duchess of Marlborough Egg; and the 1907 Sandoz Youssoupov Egg 5.

Эмаль

Эмаль (франц. Email, от франкск., smeltan — плавить), стеклоэмаль, преимущественно глухие (непрозрачные), окрашенные в различные цвета окислами металлов, легкоплавкие стекла, наплавляемые одним или несколькими тонкими слоями (эмалирование) на металл. Э. Часто называют также легкоплавкие глухие белые или окрашенные глазури, применяемые для покрытия и художеств, росписи керамических и стеклянных изделий. Основными компонентами почти всех Э. Являются двуокись кремния SiO2, борный ангидрид B2O3, окись алюминия Al2O3, окись титана TiO2, окислы щелочных и щёлочноземельных металлов, свинца, цинка, некоторые фториды и др. Э. Принято делить на грунтовые и покровные. Грунтовые Э., в которые входят сцепляющие вещества (главным образом окислы кобальта и никеля), служат для нанесения слоя, который хорошо сцепляется с металлом и является промежуточным между покровным слоем Э. И металлом. Покровные Э., которые хорошо сцепляются с металлом, наносят без грунтовой Э. Для приготовления Э. Смесь полевого шпата, песка или кварца, плавикового шпата, буры, борной кислоты, соды, селитры, криолита и другие сплавляют в печах при 1150—1550 °С и выливают в воду для грануляции. Гранулы размалывают в шаровых мельницах в присутствии воды, глины и других материалов для получения устойчивой суспензии мелких частиц, т. н. Эмалевого шликера. Металл сначала покрывают грунтовым шликером, сушат и обжигают (500—1400 °С, в зависимости от покрываемого металла), после чего наносят покровную Э. В один-два слоя с обжигом каждого слоя отдельно. Шликер наносят погружением, обливом, пульверизацией и электростатически, проводят в периодически или непрерывно действующих печах.

Э. Защищает металл от коррозии и придает ему красивый внешний вид. Наносят Э. В основном на чугун и сталь, однако в ряде случаев и на медные, алюминиевые и серебряные изделия, а также изделия из различных сплавов. Основные области применения эмалированных металлов — пищевая, химическая, фармацевтическая, электротехническая промышленность, строительство. Жароупорные и высококорозионностойкие эмалевые покрытия используются в реактивных двигателях; в аппаратах для особо агрессивных сред; при термообработке и горячей деформации специальных сплавов.

Эмали художественные — украшение Э. Золотых, серебряных и медных изделий (сосудов, ювелирных изделий и пр.). Э. — древнейшая техника, применяемая в ювелирном искусстве: холодная (без обжига) и горячая, при которой окрашенная окисями металлов пастозная масса наносится на специально обработанную поверхность и подвергается обжигу, в результате чего появляется стекловидный цветной слой. Э. Различают по способу нанесения и закрепления на поверхности материала. Перегородчатые Э. Заполняют ячейки, образованные тонкими металлическими перегородками, припаянными на металлическую поверхность ребром по линиям узора,—передают четкие линии контура. Выемчатые Э. Заполняют углубления (сделанные резьбой, штамповкой или при отливке) в толще металла отличаются большой интенсивностью цвета. Э. (чеканному, литому), прозрачная и глухая, позволяет передать объемные формы, достигать живописных эффектов, т. к. при плавлении эмалевая масса стекает с высоких частей рельефа и появляются сочетания прозрачных и непрозрачных пятен, дающие ощущение теней. В расписной (живописной) Э. Изделие из металла покрывается Э. И по ней расписывается эмалевыми красками (с 17 в. — огнеупорными). Э. Бывает также по скани (филиграни), гравировке, с золотыми и серебряными накладками. Наиболее ранние из дошедших Э. — золотые украшения и амулеты Древнего Египта, близкие по технике к перегородчатым. Лучший образец ранней европейской перегородчатой Э. — облицовка стенок алтаря в церкви Сант-Амброджо в Милане (мастер Вольвиниус 9 в.). В Византии в 10—12 вв. была развита перегородчатая Э. На золоте. К началу 12 в. сложились европейские школы Э.: маасская — в долине р. Маас, в Лотарингии (мастера Годфруа де Клер и Николай из Вердена) рейнская с Кельном во главе (мастера монахи Эйльбертус и Фридерикус) школа лиможской эмали. Европейские Э. В основном украшавшие церковную утварь, органически связаны с убранством соборов, витражами. С конца 14 — в начале 15 вв. в технике Э. Выполнялись предметы светского характера. Глухие и непрозрачные Э. Сменяются прозрачными Э. По гравировке с введением золотых линий и накладок. В 18 в. на первый план выдвинулись эмалевая портретная миниатюраи живопись, стилистически близкие станковой живописи. Трудоёмкая техника Э. Пришла в упадок в 19 в. и возродилась лишь в эпоху господства стиля «модерн» в Париже, Брюсселе, Вене — изготовление украшений, табакерок, вееров в сочетании с драгоценными камнями, жемчугом и пр. (К. Поплен, Р. Лалик, П. Грандом). В Китае Э. Известны с 7 в., получили большое развитие в 14—17 вв. Э., украшающие детали холодного оружия, коробочки, табакерки и т. п. Символическими растительными мотивами, изображениями птиц и животных. На территории СССР Э. Изготовлялись в 3 — 5 вв. в Приднепровье (браслеты, фибулы с красной, голубой, зелёной и белой Э). Сохранились перегородчатые Э Киевской Руси 11 в. Влияние Византии сказалось на русских перегородчатых Э. 12-13 вв. на серебре и золоте и средневековой грузинской Э. На золоте, отличавшейся от византийской Э. Менее тонкой технической проработкой, от русских — более ярким цветом (Хахульский складень, 12 в., Музей искусств Грузинской ССР, Тбилиси). В 16-17 вв. у московских мастеров получила распространение Э. По скани — прозрачная многоцветная Э. Густых насыщенных тонов на золотых изделиях (мастера Оружейной палаты И. Попов и др.), по сюжетам и орнаментике близкая украшению рукописей того же времени. В 17 в. в Сольвычегодске расцвело искусство расписной Э. («усольской»). Развитие расписной Э. По меди удешевило эмалевые изделия и расширило круг предметов, украшенных Э. (помимо культовых предметов, ларцы, чарки, коробочки для румян, флаконы, ложки и т. д.). В 18-19 вв. в Ростове Великом изготовлялись иконы и другие изделия в технике расписной Э. В 18 в. развилась эмалевая портретная миниатюра (Г. С. Мусикийский, А. Г. Овсов, И. П. Рефусицкий, живописец А. П. Антропов). М. В. Ломоносов разработал новую палитру эмалевых красок из отечественных материалов; был учрежден эмальерный класс в петербургской АХ (впервые упомянут в 1781). В конце 19 — начале 20 вв. изделия с Э. Изготовляли фирмы Фаберже, Хлебникова, Овчинникова, Грачева.

В СССР выпускают изделия с расписной Э., с Э. По скани, по гравировке, штампованному рельефу и др. Крупным центром производства Э. Является фабрика «Ростовская финифть» (в Ростове-Ярославском), продолжающая идущую с 18 в. традицию живописной Э. (броши, пудреницы, коробочки), в основном с декоративными цветочными композициями, а также сюжетными миниатюрами (мастера А. М. Кокин, В. В. Горский, И. И. Солдатов, В. Г. Питслин и др.).

2015-04-23

2015-04-23 533

533