План

1. Economic Problems. Industry. Agriculture. The Financial Sector.

2. Economic reforms of the 1980s and 1990s.

3. The workforce. The trade unions.

4. Major trends in the economy.

Cultural and institutional terms.

1.Economic Problems. Industry. Agriculture. The Financial Sector.

Britain was the first country to industrialise. In 1850 it had as many merchant ships as the rest of the world put together, and it led the world in most manufacturing industries and international trade. But this lead did not prove durable. Early in the 20th century it was overtaken by its rivals, the USA and Germany. After two world wars and the rapid loss of its colonial empire, Britain was unable even to maintain its position in Europe. After 1945 Britain tried to find a reasonable balance between government intervention in the economy and a largely free-market economy such as that of the United States, while both Labour and the Conservatives were generally reluctant to break from the consensus based on Keynesian economics. People seemed reluctant to make the painful adjustments that might be necessary to reverse the country’s economic decline. In fact, prosperity increased during the late 1950s and in the 1960s, diverting attention from Britain’s decline compared to its main competitors. But by the mid-1970s both Labour and Conservative economists were thinking of moving away from Keynesian economics (in principle, based upon stimulating demand by injecting large amounts of money into the economy). Eventually, it was the Conservatives who decided to break with the old economic formula in 1979, when they introduced a series of free-market reforms which improved the country’s economic performance, albeit at the cost of much social dislocation.

Every country’s first resource is land, and densely-populated Britain has little of it. Only about 2 per cent of the population work on farms. After 1945governments encouraged them, both by advice and financial inducements, to use their land effectively, and when the UK joined the European Community most farms were well equipped and highly mechanised. Now their efficiency is even embarrassing: environmentalists complain that insecticides and fertilisers used in agriculture have polluted air and water, and too much food is being produced. To relieve the problem, each year much good farmland is sold for building, and farmers are encouraged to put some land to other uses, e.g. facilities for recreation. However, agriculture is only a small part of the whole economy. For about 200 years, manufacturing has been more important, but by the 1970s it was clear that Britain’s old manufacturing industries, like textiles and shipbuilding, and some of its newer industries, like car manufacturing, were less efficient than the same industries in other Western countries. In general, the value of goods produced by a hundred workers had for many years increased much less in Britain than, for example, in West Germany. In some factories, there was simply not enough new equipment; in others, new equipment was not being used efficiently. Strikes were frequent.

|

|

|

After 1979, when Mrs Thatcher’s government came to power, some sections of the old industries improved their productivity and became more profitable than before, but some were less successful and some even failed to survive. Besides, new ‘high-tech’ industries developed, and there was a new diversity, with some growth of small-scale enterprise. Two parallel developments have affected Britain more than most other European countries: (1) the increase in the service industries, as distinct from the productive ones; (2) the increase in the proportion of people employed in ‘white collar’ jobs, as distinct from manual jobs: in fact, more than half of all working people (whether employees or self-employed) are now providing services. Although some service work is, of course, manual, less than half of all working people are in jobs traditionally associated with the working class.

It was the development of coal production which determined Britain’s economic leadership of the world in the 18th and 19th centuries. Coal mining was once a powerful industry, but since the defeat of the miners’ strike in 1985 economic reform and change have reduced the importance of the coal industry. Coal is expected to decline further. It is generally more polluting and less efficient than natural gas.

Oil and gas were discovered in the North Sea at the end of the 1960s. They turned Britain from a net importer of energy into a net exporter. British policy makers insist that energy should be derived from a balance of different sources. Easily the most controversial of these is nuclear energy. Britain established the world’s first large-scale nuclear plant in 1956. Nuclear energy became a highly emotive subject, particularly after disasters, such as Chernobyl. Besides, its real commercial cost (by the 1990s) was twice as high as for coal-fired power station. Unless a much safer and more efficient system is designed, nuclear power probably has little future. In the early 1990s Britain also started to take renewable energy sources much more seriously than before.

|

|

|

There has been a long tradition in Britain of directing the economy through the financial institutions which together are known as ‘the City’: the Bank of England, the retail and wholesale banks, insurance companies (most notably Lloyds) and the Stock Exchange of the City have for a long time played an important role in Britain’s economy.

Traditionally, the Bank of England, which serves as Britain’s central bank, has three main roles: (1) to maintain the stability and value of the currency, the pound sterling; (2) to maintain the stability of the financial system; (3) to ensure the effectiveness of the financial services sector. There are two main kinds of bank: (1) ‘retail banks’ for personal and small business accounts, also known as ‘the high street banks’; (2) ‘wholesale banks’ which handle large deposits at higher interest rates, many of these are known as ‘merchant banks’.

Lloyds is essentially a market, not a company, where different syndicates compete with each other and other insurance companies for business.

The British practice of guiding the economy through the City’s financial institutions gives rise to major problems. Those who invest in the City may be concerned with making maximum profit in the minimum amount of time, which inevitably conflicts with the national economic interest. Most industrialised countries enjoy a significantly higher level of industrial investment than Britain where banks, insurance companies, pension funds and building societies frequently prefer to invest in other areas.

When Labour returned to power, it gave the Bank of England statutory power to set interest rates, independently of government, abandoning a key lever for short-term considerations, in favour of allowing the Bank to set interest rates purely as part of long-term economic strategy. Labour also took steps to ensure that the Bank’s decisions were more open and more accountable to the House of Commons.

2.Economic reforms of the 1980s and 1990s.

In 1979 many of the old industries were owned by the state. Their managing boards were told by the new government to aim at profit, and to prepare for being sold off to the private sector. Many steel plants were eventually closed, but in a few years those which survived no longer needed subsidies. Coal production was now concentrated in the most efficient pits. No industry has probably suffered so great a change for the worse as shipbuilding, in which Britain led the world for 200 years or so. But many other industries became more competitive in the 1980s.

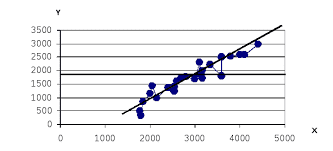

In general, from 1979 to 1997 the Conservatives put their new ideas into practice. Income tax was reduced from 33 per cent to 24 per cent. The government also increased Value Added Tax (VAT) on goods and services. It gave every encouragement to a free-market economy. Measured purely in financial terms, the results were excellent: by 1987 the FT-SE (pronounced ‘footsie’ but standing for Financial Times—Stock Exchange) index of share values was five times higher than it had been in 1983. But the belief that it would force industry to become ‘fit and lean’ led only partly to greater efficiency, as has been said, it also led to the collapse of much of Britain’s manufacturing industry.

Thatcher’s belief that ‘monetarism’ alone could produce the revolution she sought proved ill-founded. The resulting surge in unemployment dramatically increased public expenditure. By 1985 it was clear that monetarism was not a panacea for Britain’s economic problems, and it was quietly abandoned. But its damage had been considerable. By 1983, as a result of the new policy and for the first time in more than 200 years, Britain imported more manufactured goods than it exported. By 1990 Britain was in the deepest recession since 1930, and it proved longer and deeper than the recession that hit other members of the European Union. The Conservative ‘heartlands’ were particularly hard hit. The recession affected the property market, leading to a collapse of prices and wide-spread disillusionment with the Conservative party.

The Conservatives’ greatest transformation was the privatisation of government-owned enterprises. They reduced the size of the state-owned sector by over two-thirds. The greatest benefits of privatisation were that it forced prices down and forced standards of service up to the benefit of customers and shareholders. After the departure of Thatcher, the Conservatives under John Major quietly returned to a form of Keynesian economics.

There were some bright spots, too. ‘High-tech’ industries have developed in three main areas, west of London along the M4 motorway or ‘Golden Corridor’, the lowlands between Edinburgh and Dundee, nicknamed ‘Silicon Glen’, and the area between London and Cambridge. The Cambridge Science Park is the flagship of high-tech Britain. Britain publishes 100,000 new books yearly, and boasts the largest export publishing industry in the world. The majority of profitable retailers in Europe are British, too.

3.The workforce. The trade unions.

There are currently approx. 35 million people of working age in Britain. Compared with a couple of decades ago, there has been a massive change in employment patterns. There has been an increase in the proportion of people employed in ‘white collar’ jobs, as distinct from manual jobs. In fact, more than half of all working people (whether employees or self-employed) are now providing services. There has been some growth in the number of those who work for schools and hospitals, social services, the police and prisons, and in public administration, while the biggest growth has been in the finance, banking and insurance sector, along with ‘other services’, including the law, advertising, catering and entertainment.

Another recent change has been the growth of self-employment. This development was encouraged by the government through training courses, tax incentives and an ‘enterprise allowance scheme’.

In 1970 only about 20 per cent of the workforce was female compared with 46 per cent of the workforce in 1995. Other developments indicate job loss, job insecurity and workplace stress. Those in work tend to work longer hours than before, but with falling productivity, which is bad for health, standards of work, and family life. One of the reasons is that Britain has one of the least regulated labour markets of any industrialised country. There is a growing gap between the earnings of the rich and poor.

|

|

|

The most important lobby organisation for owners and managers is the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), which seeks to support industrial growth and planning, and to create a climate conducive to efficiency and profitability. The trade unions: from 1945 until 1979 the trade union movement was a central actor in the British economy. The Trades Union Congress (TUC) was established in 1868 as a coordinating body. The TUC’s concern that the workers’ interests be represented in Parliament led to the establishment of the Labour Party in 1900, and the unions dominated Labour until the 1990s. In particular, union power grew after 1945, with the number of members increasing, but with fewer and more powerful unions as a result of amalgamation. During the 1960s and 1970s the unions were so powerful that no government could operate without consulting them: ‘beer and sandwich lunches at Number Ten’ were a familiar feature of political life. The Conservative Party introduced new union laws in the 1980s and 1990s in order to restrict and regulate the power of unions and to shift the balance of power within each union, hoping that ordinary members of unions would moderate the behaviour of their leaders. Union power was further weakened by a serious fall in membership. Since the early 1990s British unions have tried to learn from their less adversarial European counterparts, changing their attitude to the European Community from hostility to enthusiasm.

Union relations with Labour have also changed. While still relying on union funding, Labour has gradually reduced union voting power at its annual Conference.

4.Major trends in the economy.

Britain is much better off in terms of economic efficiency now than it was in the 1970s and 1980s. But some trends which made it “the sick man of Europe” are still there and give cause for concern. Reasons for poor economic performance were: the stress of two world wars and the loss of empire; unlike other European powers, Britain failed to rebuild its industries in 1945. But the most complex reasons are probably cultural. Despite the major economic changes of the Industrial Revolution, the old gentry class of Britain did not oppose the rising middle class but made skilful adjustments to allow them to share power. In Britain’s private education system, a culture of respect for the professions but contempt for industry continued long after the Second World War. Britain failed to give technical and scientific subjects as much importance as its competitors, as a result Britain has one of the least trained workforces in the industrial world. Britain also fails to invest in research, which is most clearly seen in the area of Research and Development (R and D), most of which is directed towards immediate and practical problems in Britain. British companies spend less on R and D than many of their competitors in Europe and North America. Another worrying factor is the absence of ‘team spirit’: little effort is made to interest the workforce in a company’s well-being, joint consultations between management and workers are still rare, few companies offer incentive schemes for increased productivity. With its youthful energy, Labour set itself the target of curing these ills and is generally believed to be doing well.

|

|

|

Cultural and institutional terms. Keynesian economics, trade unions, the TUC, the CBI, lobbying, R and D, incentive scheme.

Questions:

1. What was the post-war ‘consensus’ regarding the country’s social and economic development?

2. Who broke it and why?

3. What were the economic problems that the reforms of the 1980s were designed to solve?

4. What were the results of the reforms of the 1980s?

5. What is the present economic situation?

References:

Левашова В. А. Современная Британия. М.: Высшая школа, 2007.

McDowall D. Britain in Close-Up. Longman Ltd., 2005.

2015-05-26

2015-05-26 1192

1192