We might have a passenger pigeon again in ten years, says author.

Will it be possible to one day bring a woolly mammoth, like this replica in a museum in Vancouver, Canada, back to life? And should we?

Will it one day be possible to bring a woolly mammoth or a Neanderthal back to life? If so, should we? How is climate change affecting the evolution and extinction of species?These are some of the questions explored in science writer Maura O’Connor’s new book, Resurrection Science: Conservation, De-Extinction And The Precarious Future of Wild Things. Traveling the world from Kenya (in search of the white rhino) to a lab in California (where a geneticist is trying to resurrect the extinct passenger pigeon), O’Connor reports on the people and places on the front lines of what has become known as resurrection science.Talking from her home in Brooklyn, she explains why the White Sands pupfish of New Mexico would have amazed Charles Darwin; how it may become increasingly necessary to genetically engineer species in order to save them; and why she has no plans to volunteer as a surrogate mother for a baby Neanderthal. You write, “When I was a kid in the 1990s, the world felt like it was on the edge of catastrophe.” Wind back the clock for us and explain how those childhood experiences got you interested in the question of extinctions. I grew up in California, where kids are taught to conserve water from an early age. The early ’90s was also a time when the idea that we need to save species at risk because of habitat destruction, pollution, and deforestation, was making news. When I was 14, I read Douglas Adams’s amazing book, Last Chance to See, which made a huge impression on me. Resurrection is a word normally associated with Jesus. That’s not what you mean, is it? [Laughs] It’s only recently become a term used to describe the de-extinction effort. The reason I wanted it as the title for the book is that in the next decades we could be bringing back species from the dead, so to speak. In the next decades we could be bringing back species from the dead. Maura O’Connor This recalls Biblical mythology, and yet it is all about science. How can we use our scientific and technological mastery to do something we’d have thought miraculous not that long ago? By trying to de-extinct species, we’re bringing together two very different things: mythology and science. You write, “Humans are in the midst of an unplanned experiment of influencing the evolution of the planet’s biodiversity.” Explain the role of climate change and the concept of “rapid evolution.” Most of us are aware that climate change is altering habitats and environments. What we don’t necessarily think about is that by changing habitats and environments, we’re influencing the forces that act upon evolution. Changes are now happening so quickly that they appear to be driving some species towards extinction because they can’t adapt fast enough. Climate change is also driving adaptations that speed up evolution. You can see species changing in response to their environment in a couple of decades. Maura O’Connor The example I write about is a species called the White Sands pup fish, in New Mexico. Four populations of this fish are located in a small area in the Tulurosa Basin. What biologists have learned studying them is that evolution occurs much faster than Darwin believed, and faster even than biologists believed 30 years ago. You can see species like the White Sands pupfish changing in response to their environment in a couple of decades. That’s pretty spectacular and scientists are becoming aware that this kind of rapid evolution is occurring in other species, likeChinook salmon or soapberry bugs.

The taxidermist’s art made this lifeless passenger pigeon lifelike. The birds went extinct in North America in 1914, but a geneticist in California now hopes to bring them back. One of the problems conservationists face is that there’s no clear definition of what a species is. Explain “the species problem” and how this can alter an animal’s status. The species problem is essentially, how do we define a species? Before the 19th century, people believed a species was divinely created and had fixed identities. Thanks to Darwin, we know that species change.But how do we define where a species begins and ends? Genetic sequencing compounds the problem because we can now look into the genetic makeup of an animal and see how closely—or not—it’s related to a distant relative.How you define a species can also alter its legal status under the Endangered Species Act. A species may be protected, but its subspecies may not be. That’s why it matters for conservationists to have an accepted definition of what a species is and is not. Sometimes conservationists have to work with strange bedfellows. Tell us about Roy McBride and the attempts to restore the Florida panther. I wanted to understand how there came to be a small population of panthers living in Florida, north of Miami and south of Disney World. When I started speaking to folks involved in the conservation effort, it became clear that McBride had played a central role.

The northern white rhino, like this one in San Diego Zoo Safari Park, is one of the rarest creatures on Earth. Can “resurrection science” help to preserve the species?

He was the person who went out in the early ’70s with the World Wildlife Fund and rediscovered this population that no one was sure even existed. In the early ’90s, he then brought mountain lions from Texas to Florida in order to do a “genetic rescue” of the Florida panther population, which had become very inbred and was suffering as a result. That effort was very successful. They went from around 30 panthers to 160-180 today. The reason McBride strikes some as an odd person to be involved with this rescue operation is that he was formerly hired by the U.S. government as a predator hunter. Before the Endangered Species Act extended protection, the government was actively involved in hunting down predators that were deemed to pose a risk to businesses landowners. Roy McBride was a very successful tracker and hunter of both mountain lions and the Mexican grey wolf. Some claim he single-handedly led to the extinction of mountain lions in Texas. I think that’s an exaggeration. And after the 1970s, he became critical to the Florida panther recovery plan. We can’t discuss extinctions without mentioning the Passenger Pigeon.Introduce us to Ben Novak and his attempts to bring them back to life. I approached the topic of extinction with some cynicism. I wasn’t convinced that it was a necessary or appropriate response to some extinction crises. So meeting Ben Novak was a very important moment for me. He’s a very passionate young man in his 20s who’s completely in love with passenger pigeons and has dedicated his young life to try and bring them back to the forests of the northeast United States.

Passenger pigeons went extinct in about one-thousandth of a percent of the time they were on Earth. Maura O’Connor Novak’s work mapping the genome of this bird has shown they’re at least 22 million years old. The first colonial settlers described seeing an incomprehensible abundance of them in American skies and forests. The last one died in 1914. And the fact that they went extinct in about one-thousandth of a percent of the time they were on Earth is truly incredible.

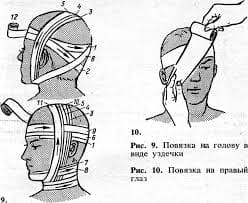

“Wanted: Adventurous woman to give birth to Neanderthal,” ran a British tabloid headline, after Harvard scientist, George Church, suggested cloning a Neanderthal. This reconstruction of a female Neanderthal is in Asturias, Spain. What Novak and his team at the University of California, Santa Cruz, hope to do is use the genetic material of its nearest living relative, the band-tailed pigeon. There’s no frozen tissue so you can’t clone a passenger pigeon. By using genetic editing tools they’ll alter the DNA of a band-tailed pigeon to passenger pigeon DNA. Once they’ve been able to genetically modify a band-tailed pigeon, they hope to incubate that genetic material in other band-tailed pigeons to produce passenger pigeons. If everything progresses as Novak hopes, we might have a passenger pigeon again in ten years. But there’s a whole other process of trying to figure out how you teach this animal to be a passenger pigeon. It’s not just DNA. There’s also animal culture and the relationship between ecology and species. And it’s far from clear that scientists understand how they could bring back those types of relationships. Kes Hillman Smith is a name most of our readers won’t be familiar with. Tell us a bit about her and your journey to Kenya in search of the white rhino. When I started writing the chapter on northern white rhinos, there were seven left in the world. Two have subsequently died of natural causes. When I started speaking to people about the history of the northern white rhino, Kes Hillman Smith’s name kept coming up. I realized I’d read about her as a child, in Last Chance to See. Kes and her husband, Frasier, have spent more than two decades trying to protect the last population inGaramba National Park. Unfortunately, that population may well become extinct in the next few years. Recently the extinct Azuay stubfoot toad leaped back to life in Ecuador. What does this tell us about extinctions? Are other species about to reappear? Absolutely. There are dozens of species thought to have gone extinct, which were then sighted sometimes many decades after the last sighting. It’s a testament to how hard it is to track and find animals in the wild. It also speaks to the resilience of some species to survive against the odds. A recent British newspaper headline read: “Wanted: Adventurous woman to give birth to Neanderthal man—Harvard professor seeks mother for cloned cave baby.” Could we one day actually back Neanderthals, and are you going to volunteer? [Laughs] Absolutely not! The press loves this story because it’s almost like the idea of time travel, and that’s endlessly fascinating for us to think about. It was discussed because of a book by George Church, of Harvard Medical School, who’s involved with some of these de-extinction initiatives.His thought was that if we wanted to create greater genetic diversity within the human population, one way to do that might be to bring back Neanderthals through genetic engineering and then incubation in a surrogate. It’s doubtful whether this is a good idea, or morally acceptable, though. Our mastery of technology is further along than our moral and ethical frameworks. At the end of the book, you say, “I have heard few cases for de-extinction that present a clear and compelling argument that justify the risks.” How did writing this book change your perspective? And are you still convinced that the world is on the edge of catastrophe? - I think the world is changing faster than many of us can comprehend. That is something for us all to think about, particularly in regard to our relationship with nature and what kind of world we want to be living in. Do we want to live in a world with wild things free from human influence? And is that even possible with climate change? My feeling about de-extinction has changed because the people I met and talked to are brilliant and passionate and had wonderful motives for wanting to bring back species that became extinct because of our ignorance and behavior.But in many of the de-extinctions being proposed, they don’t address the problems that caused the extinctions in the first place. We may be able to create woolly mammoths, which would be Asian elephants genetically engineered to survive in the Arctic. But that doesn’t solve the problem of why Asian elephants are endangered. And it certainly doesn’t solve the problem of why we’re experiencing an era of rapid climate change. I hope that will be debated and discussed more in the near future.We should make every effort to preserve wild places and wild things. But resurrection science is probably here to stay. We just have to decide the degree of intervention and influence we’re comfortable with.

2015-10-16

2015-10-16 495

495