A convertible bond (or convertible debenture) is a corporate bond that can be converted into the company's common stock under certain terms. Convertible preferred stock carries a similar "conversion privilege". These securities are intended to combine the reduced risk of a bond or preferred stock with the advantage of conversion to common stock if the company is successful. The market price of a convertible security generally represents a combination of a pure bond price (or a pure preferred stock price) plus a premium for the conversion privilege. Many convertible issues are listed on the NYSE and other exchanges, and many others are traded over-, the-counter.

Options

An option is a piece of paper that gives you the right to buy or sell a given security at a specified price for a specified period of time. A "call" is an option to buy, a "put" is an option to sell. In simplest form, these have become an extremely popular way to Speculate on the expectation that the price of a stock will go up or down. In recent years a new type of option has become extremely popular: options related to the various stock market averages, which let you speculate on the direction of the whole market rather than on individual stocks. Many trading techniques used by expert investors are built around* options; some of these techniques are intended to reduce risks rather than for speculation.

Rights

When a corporation wants to sell new securities to raise additional capital, it often gives its stockholders rights to buy the new securities (most often additional shares of stock) at an attractive price. The right is in the nature of an option to buy, with a very short life. The holder can use ("exercise") the right or can sell it to someone else. When rights are issued, they are usually traded (for the short period until ' they expire) on the same exchange as the stock or other security to which they apply.

Warrants

A warrant resembles a right in that it is issued by a company and gives the holder the option of buying the stock (or other security) of the company from the company itself for a specified price. But a warrant has a longer life—often several years, sometimes without limit. As with rights, warrants are negotiable (meaning that they can be sold by the owner to someone else), and.several warrants are traded on the major exchanges. !

Commodities and Financial Futures

The commodity markets, where foodstuffs and industrial commodities are traded in vast quantities, are outside the scope of this text. But because the commodity markets deal in “futures”—that is, contracts for delivery of a certain good at a specified future date— they have also become the center of trading for “financial futures”, which, by any logical definition, are not commodities at all.

Financial futures are relatively new, but they have rapidly zoomed in importance and in trading activity. Like options, the futures can be used for protective purposes as well as for speculation. Making the most headlines have been stock index futures, which permit investors to speculate on the future direction of the stock market averages. Two other types of financial futures are also of great importance: interest rate futures, which are based primarily on the prices of U. S. Treasury bonds, notes, and bills, and which fluctuate according to the level of interest rates; and foreign currency futures, which are based on the exchange rates between foreign currencies and the U. S. dollar. Although, futures can be used for protective, purposes, they are generally a highly speculative area intended for professionals and other expert investors.

WHAT IS A RECESSION?

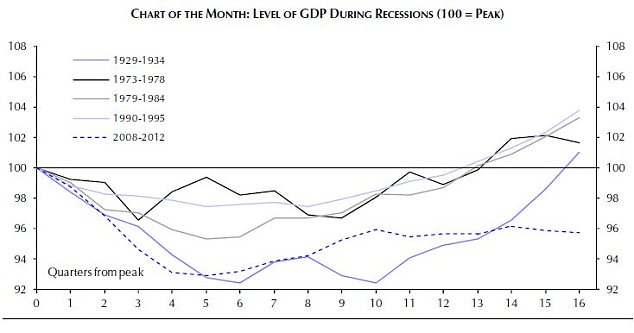

The technical measure of recession' is two 'quarters' of the year, back-to-back, where the size of the economy shrinks, as measured by GDP (Gross Domestic Product).

We remain a long way from that 2008 peak - the economy saw below-par 2.1 per cent expansion in 2010 following a 6.4 per cent plunge during the 'Great Recession' of 2008-2009.

We're now in the longest slump in more than a century.

The graph below shows how the economy has recovered after previous recessions. This downturn has been worse than the Seventies, in terms of the trajectory of the economy, and even more severe than the Great Depression of the 1930s, when GDP recovered its previous high after nearly four years.

How the recovery from recession compares with those of the past

So what can we expect for 2012 as a whole?

The median prediction from analysts is for growth of just 0.4 per cent for 2012 with the gloomiest forecasters predicting the economy will shrink by more than 1 per cent.

To get a feel for how weak this is, the average annual GDP growth from 1990 to 2008 was 2.3 per cent. And most people had been expecting the usual post-recession bounce back, as happened after the Eighties and Nineties recessions. So they'd have been hoping for growth of 4 per cent or 5 per cent a year.

THE euro crisis flared up in early April after three months of relative calm as banks got a trillion-euro helping hand from the European Central Bank. Spanish bond yields jumped on fears that Spain – the fourth biggest economy in the euro area - might be forced to follow much smaller Greece, Ireland and Portugal in being bailed-out by the rest of the euro area and the IMF. Our interactive graphic (updated April 13th) lays bare the economic and fiscal faultlines that make the crisis so intractable.

Although the whole of the euro area is now in recession, the reverse is much more severe in southern than in northern Europe. Forecasts for 2012 show Greece faring the worst, with GDP falling by over 4%, a crippling blow after already suffering four years of recession. Portugal will also take a knock as national output declines by more than 3%. One reason why investors have been fretting about Spain is that they fear that austerity will prove counter-productive in an economy already on its back. By contrast, Germany and France will manage to grow (though only a little) and the one northern country to take much of a hit will be the Netherlands.

Unemployment shows a similar north-south divide, with the overall jobless rate above 20% in Spain and Greece but only about 6% in Germany. For young people, the disjuncture is even more acute, with rates below 10% in Germany and Austria but above 50% in Spain and Greece and 35% in Portugal. Unemployment this high not only exacts a terrible social cost but also threatens to undermine public support for fiscal retrenchment.

Yet austerity is the harsh medicine being administered to the periphery in an attempt to deal with parlous public finances. Government debt at the end of 2011 was above 100% of GDP in Greece, Ireland, Italy and Portugal and budget deficits have also been most swollen on the southern and western rim of the euro area. By contrast, German government debt was around 80% of GDP and its budget balance was only mildly in the red last year.

European countries outside the single-currency zone like Britain may be counting their blessings for not joining the euro but tight trading and financial links mean that they are still being hurt by the crisis.

2018-03-09

2018-03-09 194

194