In addition to its functional and structural components, the cultural dimensions of school management have received increasing attention from researchers seeking to understand the complexities of school operations and performance. It is widely believed that a school’s cultural characteristics – the vision, beliefs, values, behavioural norms, social interactions and even symbolic artefacts associated with the school – shape the motivations, expectations and working performance of school members (Schein, 2010; Hartnell et al., 2011). In current education reforms, particular emphasis is placed on the need for a paradigm shift in beliefs about education, learning objectives, curriculum design, assessment methods, pedagogical approaches and related teacher competencies (Cheng, 2015b).

There is strong demand for school leaders to transform the existing culture of their schools to facilitate the above paradigm shift in education. In the school context, leadership for cultural initiatives involves the development of initiatives to transform or enhance a school’s cultural profile (in terms of vision, beliefs, values and behavioural norms) and ensure that school members are capable of implementing the paradigm shifts and other changes in education required to support students’ learning in the twenty-first century. Examples of leadership for cultural initiatives include transformational leadership (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2006; Mhatre and Riggio, 2014), visionary leadership (Van Knippenberg and Stam, 2014), cultural leadership (Schein, 2010) and paradigm-shift leadership (Cheng, 2011). In recent decades, most of these types of leadership have been widely addressed by researchers and deployed by practitioners to realise the dynamic contribution of leadership to cultural change.

A paradigm shift is currently underway in education worldwide. The emerging “third-wave” paradigm stresses the importance of contextualised multiple intelligences,[4], globalisation, localisation and individualisation to education (Cheng, 2005, 2015b). What changes in leadership are required to facilitate this paradigm shift in education in general and learning in particular? This question is crucial to the success of education reforms underway worldwide.

The above reconceptualisation of school leadership reveals that different types of leadership serve different purposes and suit different initiatives in school operations and professional practice. The three-part classification of leadership as functional, structural and cultural provides a new framework for conceptualising leadership by clustering key existing and emerging concepts of leadership into three groups with their own foci, and strengthening the conceptual links between leadership and the three types of school autonomy. This will cast light on the complexities and diversity of leadership and its connections with school autonomy, performance and development.

The reconceptualisation of leadership proposed in this study raises some interesting questions for researchers. How do the three categories of leadership mutually contribute to various aspects of school development, innovation and performance? How can these types of leadership be deployed to maximise the use of school autonomy, overcome existing constraints, facilitate paradigm shifts in education and create more opportunities for students’ lifelong learning and development? What kinds of leadership practices are associated with effective initiatives to enhance student learning? How can school leaders develop a comprehensive leadership profile that includes all three types of leadership activities?

School performance

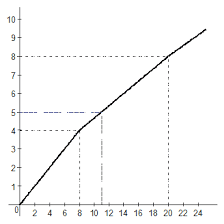

Researchers may want to determine the effects of school autonomy and leadership on school performance and student-learning outcomes. The choice of indicators of performance and outcomes often depends on academic and professional aims or policy objectives. In general, “school performance” refers to the extent or scope of the outcomes achieved by a school possessing autonomy and leadership in its local and national-education contexts, as shown in Figure 1. As school autonomy and leadership generally affect the processes and outcomes of school education, the following three basic categories of school-performance indicator can be identified:

· Enhanced functional/educational conditions: to increase the quality or broaden the scope of student performance and learning outcomes, it is necessary to improve and enhance teachers’ and students’ existing functional or educational conditions. The resulting enhanced conditions can be taken as means indicators demonstrating the extent/scope of improvements to the school’s functional/educational conditions in a certain period. Examples of this type of indicator include successful curriculum innovations, effective collaboration and teamwork, the synergetic use of resources and better coordinated work schedules.

· Enhanced pedagogical performance: the performance of pedagogical processes affects the quality of students’ learning experiences and outcomes. Enhancements to pedagogical performance are commonly used as process indicators to demonstrate the extent/scope of improvements to a school’s performance in teaching and learning in a certain period. Indicators of this kind include the adoption of student-centred approaches to teaching, the implementation of individualised learning programmes, the use of innovative learning methods and the expansion of learning opportunities. Many indicators of enhanced pedagogical performance were used in the OECD-TALIS (2013).

· Enhanced and broadened student-learning outcomes: depending on educational aims, various measures can be used to assess the quality and scope of students’ learning outcomes. Enhanced and broadened student-learning outcomes can be used as end indicators that illustrate the extent/scope of improvements to a school’s student-learning performance. Traditionally, students’ public-examination or PISA results have been taken as key indicators of learning outcomes. However, current education reforms reflect a growing emphasis on indicators that suit new educational paradigms, such as twenty-first century competencies, lifelong-learning skills and self-regulated learning (Finegold and Notabartolo, 2010; Noweski et al., 2012; Salas-Pilco, 2013; Kaufman, 2013).

Conceptually, enhanced functional/educational conditions support the performance of teachers and students in educational processes. In turn, enhanced pedagogical performance helps to improve and broaden students’ learning outcomes. Numerous researchers have sought to determine how functional/educational conditions and pedagogical processes are related to students’ learning experiences and outcomes to advance knowledge on strategies for improving student learning or school performance as a whole.

2018-03-09

2018-03-09 83

83