after Edward D. Hoch

I'm no detective. But when you are living all alone with one other man, 200 miles from the nearest settlement, and one day that only other man is murdered — well, that's enough to make a detective out of anybody.

His name was Charles Fuller, and my name is Henry Bowfort. Charlie was a full professor at Boston University when I met him, teaching an advanced course in geology while he worked on a volume concerning the effects of permafrost on mineral deposits. I was an assistant in his department, and we became friends at once. Perhaps our friendship was helped along by the fact that I was newly married to a very beautiful blonde named Grace who caught his eye from the very beginning.

Charlie's own wife divorced him some ten years earlier, and he was at the stage of his life when any sort of charming feminine companionship aroused his basic maleness.

Fuller was at his early forties at the time, a good ten years older than Grace and me, and he often talked about the project closest to his heart.

— Before I'm too old for it, he said, I want to spend a year above the permafrost line.

And one day he announced that he would be spending his sabbatical at a research post in northern Canada, near the western shore of Hudson Bay.

— I've been given a grant for eight months' study, he said. It's a great opportunity. I'll never have another like it.

— You're going up there alone? Grace asked.

— Actually, I expect your husband to accompany me. I must have looked a bit startled.

— Eight months in the wilds of nowhere with nothing but snow?

And Charlie Fuller smiled.

- Nothing but snow. How about it, Grace? Could you give him up for eight months?

— If he wants to go, she answered loyally. She had never tried to stand in the way of anything I'd wanted to do.

We talked about it for a long time that night, but I already knew 1 was hooked. I was on my way to northern Canada with Charlie Fuller.

The cabin — when we reached it by plane and boat and snowmobile — was a surprisingly comfortable place, well stocked with enough provisions for a year's stay. We had two-way radio contact with the outside world, plus necessary medical supplies and a bookcase full of reading material, all provided by the foundation that was financing the permafrost study.

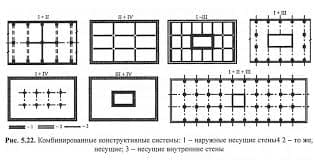

The cabin consisted of three large rooms — a laboratory for our study, a combination living-room-and-kitchen, and a bedroom with a bath in one corner. We'd brought our own clothes, and Fuller had brought a rifle, too, to discourage animals.

The daily routine with Charlie Fuller was great fun at first He was surely a dedicated man, and one of the most intelligent I'd ever known. We rose early in the morning, had breakfast together and then went off in search of ore samples. And the best of all in those early days, there was the constant radio communication with Grace. Her almost nightly messages brought a touch of Boston to the Northwest Territory.

But after a time Grace's messages thinned to one or two a week, and finally to one every other week. Fuller and I began to get on each other's nerves, and often in the mornings I was awakened by the sound of rifle fire as he stood outside the cabin door taking random shots at the occasional owl or ground squirrel that wandered near. We still had the snowmobile, but it was 200 miles to the nearest settlement at Caribou, making a trip into town out of the question.

Once, during the evening meal, Fuller said,

— Bet, you miss her, don't you, Hank?

— Grace? Sure I miss her. It's been a long time.

— Think she's sitting home nights waiting for us — for you? I put down my fork.

- What's that supposed to mean, Charlie?

— Nothing — nothing at all.

But the rest of the evening passed under a cloud. By this time we had been up there nearly five months, and it was just too long.

It was fantastic, it was unreasonable, but there began to develope between us a sort of rivalry for my wife. An unspoken rivalry, to be sure, a rivalry for a woman nearly 2,000 miles away — but still a rivalry.

— What do you think she's doing now, Hank? or

— I wish Grace were here tonight. Warm the place up a bit. Right, Hank?

Finally one evening in January, when a heavy snow had made us stay in the cabin for two long days and nights, the rivalry came to a head. Charlie Fuller was seated at the wooden table we used for meals and paperwork, and I was in my usual chair facing one of the windows.

— We're losing a lot of heat out of this place, I said. Look at those icicles.

— I'll go out later and knock them down, he said. I could tell he was in a bad mood and suspected he'd been drinking from our supply of Scotch.

— We might make the best of each other, I said. We're stuck here for another few months together.

— Worried, Hank? Anxious to be back in bed with Grace?

— Let's cut out the cracks about Grace, huh? I'm getting sick of it, Charlie.

— And I'm sick of you, sick of this place!

— Then let's go back.

— In this storm?

— We've got the snowmobile.

— No. This is one project I can't walk out on.

— Why not? Is it worth this torture day after day?

- You don't understand. I didn't start out life being a geologist. My field was biology, and I had great plans for being a research scientist at some major pharmaceutical house. They pay very well, you know.

— What happened?

— The damnedest thing, Hank. I couldn't work with animals. I couldn't experiment on them, kill them. I don't think I could ever kill a living thing.

— What about the animals and birds you shoot at?

— That's just the point, Hank. I never hit them! I try to, but I purposely miss! That's why I went into geology. That was the only field in which I wouldn't make a fool of myself.

— You couldn't make a fool of yourself, Charlie. Even if we went back today, the university would still welcome you. You'd still have your professorship.

— I've got to succeed at something, Hank. Don't you understand? It's too late for another failure — too late in life to start over again!

He didn't mention Grace the rest of that day, but I had the sensation that he hadn't just been talking about his work. His first marriage had been a failure, too. Was he trying to tell me he had to succeed with Grace?

I slept poorly that night, first because Charlie had decided to walk around the cabin at midnight knocking icicles from the roof, and then because the wind had changed direction and howled in the chimney. I got up once after Charlie was in bed, to look outside, but the windows were frosted over by the wind-driven snow, and I could see nothing.

Toward morning I drifted into an uneasy sleep, broken now and then by the bird sounds which told me that the storm had ended. I heard Charlie preparing breakfast, though I paid little attention, trying to get a bit more sleep.

Then, sometime later, I sprang awake, knowing I had heard it. A shot! Could Charlie be outside again, firing at the animals? I waited for some other sound, but nothing reached my ears except the perking of the coffee pot on the gas stove. Finally I got out of bed and went into the other room.

2020-05-12

2020-05-12 290

290