1. Reading the source text and preparing to translate.

2. Drafting.

3. Evaluating and Revising.

4. Proofreading.

5. Translating the text title.

6. Making the final copy.

Full-length written translation entails producing an unabridged full-scale written version of the original text in a different language. The whole source text is translated as it stands and the target text has the exact size or proportions of the original.

Full-length written translation is the main type of technical translation due to the following reasons:

1) scientific and technical information intended for practical use (patents, scientific and technical articles, engineering maintenance manuals, operational and maintenance handbooks for various types of instruments as well as other types of instructional literature, consumer information, publicity and information from manufacturers, etc.) is processed in the form of a full-length written translation;

2) other types of technical translation are abridged or condensed versions of full-length written translation;

3) only full-length translation involves all stages and steps (i.e. rules) of the translation process. In other types of sci-tech translation you will not always follow them in a rigid order, you may skip some stages or steps, or work with two or more stages at once.

Full-length written translation is done according to a specific set of rules and involves several stages.

As you learn and practice these stages, keep in mind that you should always follow them in a rigid order. Dividing the process into these stages will help you to save time and produce an adequate translation. It will also help you to see how to improve your translating skills and working efficiency.

1. Reading the source text and preparing to translate.

The first major stage in translating is, of necessity, reading the source text. During this stage we process the necessary information which forms the basis of our understanding of the text as readers and our transformation of it as translators. We are preparing to translate.

Before you translate, first you should 'make sense' of the text. You should read and analyze it to discover its content (infer the text-type, и cognize the thematic structure of the original, identify main ideas and supporting details, the writer's purpose in producing the text, etc.).

Read the whole source language text closely to get an adequate understanding of it. Look up any unfamiliar words. Mark and clarify obscure grammatical or syntactic structures. If necessary, read the text carefully several times, consulting dictionaries and other reference materials.

You should be able to identify and define special terminology and vocabulary used in the text. Look both for technical words and for words that are clearly being used in a special sense. Understanding terms is essential to adequate translation. Consult specialized dictionaries, encyclopaedias, or other reference materials. If necessary, refer to qualified specialists for detailed information, professional or expert advice. Remember the golden rule essential to sci-tech translation: never be too proud or embarrassed to ask for help or advice.

It is common knowledge that context is a powerful preventative against any misunderstanding of meanings. Individual meanings of words are revealed in the context (the parts of the text that precede or follow a specified word or passage and can influence its meaning). For instance, the noun vehicle, if used out of context, would mean different things: 1) means of conveyance or transport (засіб пересування), 2) a liquid, as oil, in which a paint pigment is mixed before being applied to a surface (розчинник), 3) a chemically inert substance used as a medium for active remedies (середовище для ліків), 4) а subbstance, or device that readily conducts heat, electricity, sound (npовідник), 5) a person who carries or spreads a disease (носій інфекції). It is only in combination with other words that it reveals its actual meaning: a motor vehicle, space vehicle, ink vehicle, vehicle of disease. In some cases such minimum context (microcontext) fails to reveal the meaning of a word or technical term, and a broader context, or macrocontext, is necessary. That is why you should always read the whole source text closely before translating it.

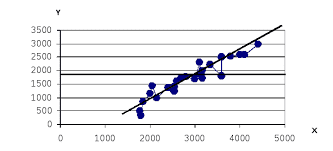

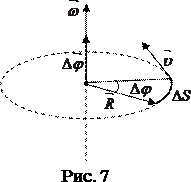

Many books, informational articles, instructions include drawings, diagrams, maps, graphs, and illustrations. Do not skip over these visual aids — study them. They have been carefully selected and designed in make information clearer and more understandable.

2. Writing a draft of the target language text (Drafting).

During this stage you work with separate parts of the source text. The stage includes three separate actions, or steps:

1) Parsing and idea-recovery. Step 1 in the translation process is parsing (analysis in terms of grammatical constituents, identifying the parts of speech, syntactic relations, etc.) and idea-recovery.

Break the text down into smaller units. Choose one segment and read it closely. Analyze it in terms of grammatical constituents and their syntactic relations. Then try to absorb its meaning making a mental outline: state the main idea and find details that support it (reasons, examples):

There is the problem of the size of the unit of translation (the unit that the translator processes in the course of translating). Does one translate in words, phrases, sentences, or in larger units? The notion 'unit of translation' (UT) has been defined in the following terms:

The smallest segment of a source language text which can be translated, as a whole, in isolation from other segments. It normally ranges from the word through the clause (syntactic construction containing a subject and predicate and forming part of a sentence or constituting a whole simple sentence) to the paragraph (group of closely connected sentences which make one main idea clear). It could be described as a small as is possible and as large as is necessary, though some translators would say that it is a misleading concept, since the only unit of translation is the whole text.

If we ask what the unit is that the translator actually processes in the course of translating, we discover that the unit tends to be the j sentence. It is to be expected, for both psychological and linguistic reasons, since the sentence develops one idea about a topic and ' tends to be about the right length to be entered on the visual-spatial scratch pad in the translator's short-term working memory.

2) Translating. Step 2 involves translation.

Translate the chosen segment of the source language text. Render it into the target language in your own words without referring to the original. Do not try to translate your segment word for word. When you translate, set the original aside to avoid literal translation.

Remember that a good translation should give a complete transcript I of the ideas of the original work. Be prepared to take some risks and to create a translation that owes more to the meaning of the source text than its grammatical structure. Focus on meaning at the expense of reflecting source language structure.

3) Checking against the original for accuracy (monitoring translation performance). Step 3 concerns decisions on the quality of translation output and involves checking, verifying or correcting one's it language production. This step includes checking back to the source language text to make sure that its basic literal meaning has not been misinterpreted in the; target text.

Compare and contrast the target language and the source language segments. Evaluate and revise your translation.

On this basis you produce a draft translation (tentative translation) о) the whole source language text.

3 Evaluating and Revising (Stylistic Editing).

During this stage you evaluate and revise, that is, edit your entire Draft translation and make the necessary changes to improve it.

A lot of this stage of textual editing is done on the target text as a target language object in its own right, without reference to the. source text. In a sense, therefore, the process of stylistic editing is a post-translational operation used for tidying up an almost complete target text, and is done with as little reference as possible to the source text.

A target text is only really complete after careful editing, students sometimes think that translators write exactly what they want to say the first time. Any draft translation, even one written by an experienced translator, has some weaknesses that can be corrected or improved. As a result, all translators — including you — must be able to evaluate what they have written. The capacity to judge one's own translation output is considered a facet of translation competence; the better the translator's awareness of his/her output quality, the more competent he/she is likely to be. Remember that draft translation is only a beginning. You should have time later t ' make improvements.

To improve a draft, you first must evaluate, or make judgments about, the strengths and weaknesses of the translation. To evaluate your translation, consider three aspects: content, organization, and style. Rather than trying to judge everything at once, nine only one of these aspects at a time.

Content refers to what you have said, i.e. to the information you have rendered into the target language.

Organization concerns the way you have arranged the information. Style deals with your choice of words and sentences. As you evaluate each aspect, you will be deciding what works and what does not work in your draft translation.

When you evaluate, try these techniques:

When you evaluate, try these techniques:

1) set your draft aside for a while so that you can come back to it with the fresh eye of a reader;

2) read the draft several times, considering just one aspect each time (with these readings try to pull back from what you have written, reading it as though you were a member of the audience who has never seen the paper before);

3) read your draft translation aloud, to hear any awkward language;

4) ask someone to read your draft and comment on its strengths and weaknesses.

Once you have identified problems, experimented with changes that will improve your work, you move around words, phrases, and ideas, you are revising your draft translation to improve its content, organization, and style. When you evaluate, you identify problems with your translation. When you revise, you make changes to improve it or to correct mistakes.

Consider the aspects of content, organization, and style. Whichever aspect you want to work on, you can usually improve your translation with a combination of four basic techniques:

1) add words, sentences that will make the meaning clearer;

2) cut, or remove words, phrases, sentences that are unnecessary;

3) reorder, or rearrange words, phrases, sentences or ideas so that the flow of words is logical and easy to follow;

4) replace the words that do not work with wording.

Editing is a process that can take place at various points in the target text production process. Revision takes place while writing is going on and you work over target texts after they have been written.

Translation is a language task that requires intensive 'real-time editing', that is additions, amendments and deletions that, take place as translators proceed through the text (virtually instantaneous output repair we see when we observe translation being done in real time). This real-time editing can be thought of as the translators' opportunity to intervene to improve their output. Translators' ability to repair output during the course of their work into the target language (editing ability, ability to edit output, monitoring ability) is seen as a desirable facet of translation competence.

Nevertheless, experienced translators see revision as a whole text task. You may do some editing while you are translating the original text. But revision is often easier and more effective with a complete draft in hand. Many of the problems you thought about while you were translating can be easily addressed at this stage.

During this stage you check your final draft for errors in grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

The term proofreading comes from publishing. After the printer has made press plates for a book or articles, a set of trial pages, called proofs, is run off. These proofs are checked carefully to correct all mistakes before thousands of copies roll off the press.

Proofreading is another important stage of the translation process. In the proofreading stage, you carefully reread your revised draft translation. Your purpose in this reading, however, is different from your purpose in previous readings. This time you look for and correct mistakes in grammar, usage, spelling and punctuation. Such errors can distract the reader from the ideas in your translation.

When you proofread, use these techniques:

1) set your revised draft aside for a while so that it is easier to find mistakes;

2) if you made any revisions, recopy the draft before you proofread;

3) cover with blank paper all lines except the one you are reading to help you concentrate;

4) check all doubtful spellings, points of grammar, usage.

Also refer to the following Guidelines for Proofreading. The questions will help you identify common errors.

2015-08-21

2015-08-21 711

711