Marriages, like chemical unions, release upon dissolution packets of the energy locked up in their bonding. There is the piano no one wants, the cocker spaniel no one can take care of. Shelves of books suddenly stand revealed as burdensomely dated and unlikely to be reread; indeed, it is difficult to remember who read them in the first place. And what of those old skis in the attic? Or the doll house waiting to be repaired in the basement? The piano goes out of tune, the dog goes mad. The summer that the Turners got their divorce, their swimming pool had neither a master nor a mistress, though the sun beat down day after day, and a state of drought was declared in Connecticut.

It was a young pool, only two years old, of the fragile type fashioned by laying a plastic liner within a carefully carved hole in the ground. The Turners’ side yard looked infernal while it was being done; one bulldozer sank into the mud and had to be pulled free by another. But by midsummer the new grass was sprouting, the encircling flagstones were in place, the blue plastic tinted the water a heavenly blue, and it had to be admitted that the Turners had scored again. They were always a little in advance of their friends. He was a tall, hairy-backed man with long arms, and a nose flattened by football, and a sullen look of too much blood; she was a fine-boned blonde with dry blue eyes and lips usually held parted and crinkled as if about to ask a worrisome, or whimsical, question. They never seemed happier, nor their marriage healthier, than those two summers. They grew brown and supple and smooth with swimming. Ted would begin his day with a swim, before dressing to catch the train, and Linda would hold court all day amid crowds of wet matrons and children, and Ted would return from work to find a poolside cocktail party in progress, and the couple would end their day at midnight, when their friends had finally left, by swimming nude, before bed. What ecstasy! In darkness the water felt mild as milk and buoyant as helium, and the swimmers became giants, gliding from side to side in a single languorous stroke.

The next May, the pool was filled as usual, and the usual after-school gangs of mothers and children gathered, but Linda, unlike her, stayed indoors. She could be heard within the house, moving from room to room, but she no longer emerged, as in the other summers, with a cheerful tray of ice and brace of bottles, and Triscuits and lemonade for the children. Their friends felt less comfortable about appearing, towels in hand, at the Turners’ on weekends. Though Linda had lost some weight and looked elegant, and Ted was cumbersomely jovial, they gave off the faint, sleepless, awkward-making aroma of a couple in trouble. Then, the day after school was out, Linda fled with the children to her parents in Ohio. Ted stayed nights in the city, and the pool was deserted. Though the pump that ran the water through the filter continued to mutter in the lilacs, the cerulean pool grew cloudy. The bodies of dead horseflies and wasps dotted the still surface. A speckled plastic ball drifted into a corner beside the diving board and stayed there. The grass between the flagstones grew lank. On the glass-topped poolside table, a spray can of Off! had lost its pressure and a gin-and-tonic glass held a sere mint leaf. The pool looked desolate and haunted, like a stagnant jungle spring; it looked poisonous and ashamed. The postman, stuffing overdue notices and pornography solicitations into the mailbox, averted his eyes from the side yard politely.

Some June weekends, Ted sneaked out from the city. Families driving to church glimpsed him dolefully sprinkling chemical substances into the pool. He looked pale and thin. He instructed Roscoe Chace, his neighbor on the left, how to switch on the pump and change the filter, and how much chlorine and Algitrol should be added weekly. He explained he would not be able to make it out every weekend — as if the distance that for years he had traveled twice each day, gliding in and out of New York, had become an impossibly steep climb back into the past. Linda, he confided vaguely, had left her parents in Akron and was visiting her sister in Minneapolis. As the shock of the Turners’ joint disappearance wore off, their pool seemed less haunted and forbidding. The Mur-taugh children — the Murtaughs, a rowdy, numerous family, were the Turners’ right-hand neighbors — began to use it, without supervision. So Linda’s old friends, with their children, began to show up, «to keep the Murtaughs from drowning each other». For if anything were to happen to a Murtaugh, the poor Turners (the adjective had become automatic) would be sued for everything, right when they could least afford it. It became, then, a kind of duty, a test of loyalty, to use the pool.

July was the hottest in twenty-seven years. People brought their own lawn furniture over in station wagons and set it up. Teenage offspring and Swiss au-pair girls were established as lifeguards. A nylon rope with flotation corks, meant to divide the wading end from the diving end of the pool, was found coiled in the garage and reinstalled. Agnes Kleefield contributed an old refrigerator, which was wired to an outlet above Ted’s basement workbench and used to store ice, quinine water, and soft drinks. An honor system shoebox containing change appeared beside it; a little lost-and-found — an array of forgotten sunglasses, flippers, jtowels, lotions, paperbacks, shirts, even underwear — materialized on the Turners’ side steps. When people, that July, said, «Meet you at the pool», they did not mean the public pool past the shopping center, or the country-club pool beside the first tee. They meant the Turners’. Restrictions on admission — were difficult to enforce tactfully. A visiting Methodist bishop, two Taiwanese economists, an entire girls’ Softball team from Darien, an eminent Canadian poet, the archery champion of Hartford, the six members of a black rock group called the Good Intentions, an ex-mistress of Aly Khan, the lavender-haired mother-in-law of a Nixon adviser not quite of Cabinet rank, an infant of six weeks, a man who was killed the next day on the Merritt Parkway, a Filipino who could stay on the pool bottom for eighty seconds, two Texans who kept cigars in their mouths and hats on their heads, three telephone linemen, four expatriate Czechs, a student Maoist from Wesleyan, and the postman all swam, as guests, in the Turners’ pool, though not all at once. After the daytime crowd ebbed, and the shoebox was put back in the refrigerator, and the last au-pair girl took the last goosefleshed, wrinkled child shivering home to supper, there was a tide of evening activity, trysts (Mrs. Kleefield and the Nicholson boy, most notoriously) and what some called, overdramatically, orgies. True, late splashes and excited guffaws did often keep Mrs. Chace awake, and the Murtaugh children spent hours at their attic window with binoculars. And there was the evidence of the lost underwear.

One Saturday early in August, the morning arrivals found an unknown car with New York plates parked in the garage. But ears of all sorts were so common — the parking tangle frequently extended into the road — that nothing much was thought of it, even when someone noticed that the bedroom windows upstairs were open. And nothing came of it, except that around suppertime, in the lull before the evening crowds began to arrive in force, Ted and an unknown woman, of the same physical type as Linda but brunette, swiftly exited from the kitchen door, got into the car, and drove back to New York. The few lingering babysitters and beaux thus unwittingly glimpsed the root of the divorce. The two lovers had been trapped inside the house all day; Ted was fearful of the legal consequences of their being seen by anyone who might write and tell Linda. The settlement was at a ticklish stage; nothing less than terror of Linda’s lawyers would have led Ted to suppress his indignation at seeing, from behind the window screen, his private pool turned public carnival. For long thereafter, though in the end he did not marry the woman, he remembered that day when they lived together like fugitives in a cave, feeding on love and ice water, tiptoeing barefoot to the depleted cupboards, which they, arriving late last night, had hoped to stock in the morning, not foreseeing the onslaught of interlopers that would pin them in. Her hair, he remembered, had tickled his shoulders as she crouched behind him at the window, and through the angry pounding of his own blood he had felt her slim body breathless with the attempt not to giggle. August drew in, with cloudy days. Children grew bored with swimming. Roscoe Chace went on vacation; to Italy; the pump broke down, and no one repaired it. Dead dragonflies accumulated on the surface of the pool. Small deluded toads hopped in and swam around hopelessly. Linda at last returned. From Minneapolis she had gone on to Idaho for six weeks, to be divorced. She and the children had burnt faces from riding and hiking; her lips looked drier and more quizzical than ever, still seeking to frame that troubling question. She stood at the window, in the house that already seemed to lack its furniture, at the same side window where the lovers had crouched, and gazed at the deserted pool. The grass around it was green from splashing, save where a long-lying towel had smothered a rectangle and left it brown. Aluminum furniture she didn’t recognize lay strewn and broken. She counted a dozen bottles beneath the glass-topped table. The nylon divider had parted, and its two halves floated independently. The blue plastic beneath the colorless water tried to make a cheerful, otherworldy statement, but Linda saw that the pool in truth had no bottom, it held bottomless loss, it was one huge blue tear. Thank God no one had drowned in it. Except her. She saw that she could never live here again. In September the place was sold to a family with toddling infants, who for safety’s sake have not only drained the pool but have sealed it over with iron pipes and a heavy mesh, and put warning signs around, as around a chained dog.

Exploring Ideas and Questions for Discussion

1. What idea does the author express in the first paragraph of the story? What lexical means does the author use to express it vividly?

2. What are the main characters of the story? Can you say that the swimming pool is also a sort of character, sometimes even more prominent than the Turners?

3. What are the stages the Turners go through in the story? What happens to the pool? Does the pool symbolize the Turners’ history? In what way?

4. The pool is the topical word inthe story. What is it associated with in various paragraphs? What epithets, similes and metaphors does the author use to describe it?

5. How does the tone of the story change as the events develop? What words show this? (Investigate the connotational components of meaning in their semantic structures.)

6. What is the meaning of the suspended metaphor at the end of the story? What words symbolize the death of the Turners’ family?

7. What’s the climax of the story? How can you determine it semantically?

8. Interprete the title of the story. What’s the message of the writer to the reader?

Ритм семантической структуры текста

(анализ рассказа Джона Апдайка

«Осиротевший бассейн»)

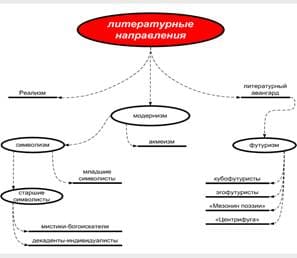

Главной темой рассказа Джона Апдайка «Осиротевший бассейн» (The Orphaned Swimming Pool) является развод. Автор прослеживает все фазы постепенного распада счастливой семьи, перерождения ее в двух одиноких, отчаявшихся людей. Апдайк описывает не только прямые признаки разрушения семейных отношений, но и косвенные — через историю бассейна во дворе семьи Тернеров, который становится лакмусовой бумажкой их семейной жизни.

Своеобразие рассказа в том, что бассейн является его «главным героем». Именно состояние бассейна иллюстрирует отношения между Линдой и Тедом. Слово «бассейн» (the pool, the swimming pool) является определяющим для понимания авторской идеи, недаром оно выносится

в заголовок рассказа. Повтор этого слова определяет ритм семантической и тематической структуры рассказа (мы понимаем ритм как регулярное повторение определенного семантического элемента на протяжении рассказа).

Текст этого рассказа отличается четкой архитектоникой, поддерживающей его «внутреннюю композицию»: он состоит из семи частей-абзацев. Первый абзац — это размышления автора о разводе. Когда семьи распадаются, все вещи, считавшиеся нужными в семье, становятся заброшенными. Никому они больше не нужны: ни кукольный дом в подвале, ни старые лыжи на чердаке, ни книги на полках. И бассейн Тернеров остался без присмотра хозяев, осиротел в одно засушливое лето в Коннектикуте.

Во втором абзаце описывается постройка бассейна. Тернеры завели бассейн как ребенка, и этим снова «обставили» своих друзей в негласном соревновании. Они никогда не казались более счастливыми, а их семья — более крепкой, чем в те два лета, когда был бассейн. Автор персонифицирует бассейн, характеризуя этот объект необычными эпитетами: It was a young pool, only twoyears old, of a fragile type. Прилагательные young, fragile часто употребляются при описании людей, fragile — особенно женщин. Хотя слово «бассейн» употребляется во втором абзаце всего один раз, его тема дополняется использованием слов water, wet, swim, swimming:

the water felt mild as milk and buoyant as helium;

to begin a day with a swim;

to court all day amid crowds of wet matrons and children;

to swim nude at night;

to grow brown... by swimming.

Семья Тернеров постоянно пользуется бассейном: Тед купается утром до отъезда на работу, Линда весь день принимает своих подруг с детьми, вечером — импровизированные вечеринки. Бассейн — источник и показатель их семейного счастья, его вода описывается словами: cerulean pool, a heavenly blue water; небесно-голубой цвет — как будто символ счастья, даже поднос с угощеньем для детей, который систематически выносит из дома Линда, описывается прилагательным cheerful, олицетворяя атмосферу в семье и доме. Итак, во втором абзаце тема бассейна ассоциируется с темой семейного счастья.

Следующий абзац на тематическом уровне поддерживается изменением семантики. В тексте появляются слова, коннотирующие опасность. На следующее лето у бассейна снова собираются мамаши с детьми, но Линда уже не так приветлива с гостями, они чувствуют себя неудобно и вскоре перестают появляться у Тернеров — они испускают аромат пары, у которой не все в порядке. Линда с детьми уезжает, Тед остается ночевать

в Нью-Йорке. Бассейн покинут всеми. Слово «бассейн» употребляется

в абзаце уже пять раз, и настойчивость этого лексического повтора привлекает к себе внимание, подчеркивая важность происходящего. «Мрачнеет» и ассоциативный ряд, сопровождающий этот образ. Какими же словами обыгрывается тема бассейна в этом абзаце?

Linda fled with the children to her parents in Ohio (to flee — run away as if from danger);

dead horseflies, the still surface,... cerulean pool grew cloudy;

a spray Off! had lost its pressure;

gin-and-tonic glass held a sere mint leaf (sere — poetical for «dry»).

В коннотации значения каждого слова пульсирует опасность, конец, покой, смерть. Небесно-голубая вода мутнеет. Бассейн вновь описывается персонифицирующими эпитетами desolate, haunted, poisonous, ashamed. Он заброшен, ядовит, его стыдятся. Он сравнивается автором со зловонным источником в джунглях. Семантическая структура абзаца несет идею конца, смерти. От него бегут как от смерти, его боятся как смерти. Знакомые и друзья Тернеров испытывают шок, видя, как разрушается семья, сторонятся их.

Следующий абзац рисует новый этап в жизни бассейна. Тед пытается оживить его, поддержать его деятельность. Действия Теда описываются следующими словосочетаниями: to sprinkle chemical substances into the pool, to switch on the pump, to change the filter, to add chlorine and Algitrol weekly. Абзац изобилует химическими и техническими терминами, они как бы показывают всю искусственность стараний Теда — семьи больше нет, у бассейна больше нет хозяев. Тед поручает уход за бассейном соседям слева. Шок от отъезда Тернеров постепенно проходит, и бассейном начинают пользоваться все, кто лоялен к Тернерам.

Мысль об обездоленности бассейна еще более усиливается в следующем абзаце. Осиротевший бассейн посещают все от подростков и заокеанских нянь с детьми до заезжего епископа Методистской церкви, филиппинца, техасцев и студента-маоиста. Там устраиваются любовные свидания и ночные оргии. Таким образом, бассейн ассоциируется в сознании людей с местом разгула страстей, чем-то порочным. Подспудная мысль автора — развод порочен.

Дополнительный временной ритм рассказа создает методичное упоминание автором месяцев лета, когда случился развод. В мае появляются первые признаки разлада в семье, и бассейн пустеет. В июне Тед еще пытается ухаживать за ним, в июле, самом жарком за последние двадцать семь лет, как утверждает автор, бассейн превращается в место публичных встреч. Апогей наступает в августе, когда Тед тайно привозит в свой дом причину развода — свою любовницу, и они проводят в доме весь день как пленники, тихие и голодные. Тед наблюдает, как «его личный бассейн превратился в публичный карнавал». Он негодует, но ничего сделать не может.

Август приносит облачные дни, детям надоело купаться, сосед уезжает в отпуск в Италию, бассейн окончательно умирает. Всюду царит разрушение: the pump broke down, dead dragonflies accumulated on the surface of the pool, the deserted pool, aluminium furniture lay strewn and broken. Семантика глаголов в описании бассейна показывает разрушение, прилагательных и причастий — одиночество и смерть. Вот то, что случилось

с семьей Линды, это она видит, когда возвращается в свой бывший дом. Голубой пластик на дне бассейна еще пытается создать бодрящее впечатление, но дна Линда не видит. Бассейн бездонен, как бездонно ее горе. Бассейн заключает в себе огромную потерю, он — огромная голубая слеза (...it held bottomless loss, it was one huge blue tear...). Эта развернутая метафора, включающая в себя гиперболу (слеза, укрупненная до бассейна) и литоту (сравнение большого бассейна с крошечной слезой), являет собой наивысшую точку напряжения в рассказе, кульминацию в развитии действия. Бассейн приобретает символическое значение, становясь знаком смерти семейных отношений Тернеров.

В сентябре дом продают семье с маленькими детьми. Бассейн осушают, покрывают тяжелыми сетями, окружают предостерегающими от опасности табличками, как предупреждают о цепной собаке. Тема бассейна связана с темой страха. Как видим, в последней части рассказа бассейн ассоциируется с разрушением, одиночеством и смертью, с огромным несчастьем, опасностью, которая подстерегает каждого.

Как видим, рассказ Апдайка определяется особым ритмом изложения. Основная тема рассказа — развод — раскрывается, во-первых, через значимость хронологического ритма (май — август): автор систематично, по месяцам, отслеживает развитие событий; во-вторых, основная тема постоянно сочетается со своим олицетворением — образом бассейна;

в-третьих, косвенно, образ бассейна становится символом, включающим в себя самые различные значения, он варьируется, ассоциируясь с различными подтемами (счастья, беды, разгула, смерти, осознания потери, страха), характеризующими фазы развода и отношение автора и героев рассказа к нему; в четвертых, на семантическом уровне, метричная монотонность повтора ключевого слова сочетается с вариативностью лексики, передающей постепенное изменение в отношениях героев.

4

Ernest Hemingway

A Farewell to Arms

Chapter I

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves.

The plain was rich with crops; there were many orchards of fruit trees and beyond the plain the mountains were brown and bare. There was fighting in the mountains and at night we could see the flashes from the artillery. In the dark it was like summer lightning, but the nights were cool and there was not the feeling of a storm coming.

Sometimes in the dark we heard the troops marching under the window and guns going past pulled by motor-tractors. There was much traffic at night and many mules on the roads with boxes of ammunition on each side of their pack-saddles and gray motor-trucks that carried men, and other trucks with loads covered with canvas that moved slower in the traffic. There were big guns too that passed in the day drawn by tractors, the long barrels of the guns covered with green branches and green leafy branches and vines laid over the tractors. To the north we could look across a valley and see a forest of chestnut trees and behind it another mountain on this side of the river. There was fighting for that mountain too, but it was not successful, and in the fall when the rains came the leaves all fell from the chestnut trees and the branches were bare and the trunks black with rain. The vineyards were thin and bare-branched too and all the country wet and brown and dead with the autumn. There were mists over the river and clouds on the mountain and the trucks splashed mud on the road and the troops were muddy and wet in their capes; their rifles were wet and under their capes the two leather cartridge-boxes on the front of the belts, gray leather boxes heavy with the packs of clips of thin, long 6.5 mm. cartridges, bulged forward under the capes so that the men, passing on the road, marched as though they were six months gone with child.

There were small gray motor cars that passed going very fast; usually there was an officer on the seat with the driver and more officers in the back seat. They splashed more mud than the camions even and if one of the officers in the back was very small and sitting between two generals, he himself so small that you could not see his face but only the top of his cap and his narrow back, and if the car went especially fast it was probably the King. He lived in Udine and came out in this way nearly every day to see how things were going, and things went very badly.

At the start of the winter came the permanent rain and with the rain came the cholera. But it was checked and in the end only seven thousand died of it in the army.

2020-01-14

2020-01-14 2370

2370