Key terms: absolutive time (the past, the present, the future), relative time (priority – “relative past”, simultaneity – “relative present”, posteriority – “relative future”), factual time, tense, “primary, absolutive, or retrospective time” (past vs. non-past), “historic present”, “preterite of modesty”, “relative, or prospective time” (future vs. non-future), modal colouring, obligation, volition

Ривлина А.А. Теоретическая грамматика английского языка

| UNIT 14 | ||

| ГЛАГОЛ: КАТЕГОРИЯ ВИДА | VERB: ASPECT | |

| Категориальное значение вида. Лексические и грамматические способы выражения аспектного значения; их взаимозависимость. Различные подходы к трактовке аспектных глагольных форм. Система глагольных видовых категорий в английском языке: категория развития (продолженные и не-продолженные, неопределенные, индефинитные формы) и категория ретроспективной координации (перфектные и неперфектные формы); чисто видовое значение форм продолженного вида и смешанное видо-временное значение перфекта. Оппозиционное представление категории вида в английском языке. Случаи контекстной редукции видовых оппозиций. Представление категории вида в неличных формах глагола. | The categorial meaning of aspect. Lexical and grammatical means of expressing aspective meaning; their interdependence. Various approaches to the aspective verbal forms. The system of verbal aspective categories in English: the category of development (continuous vs. non-continuous) and the category of retrospective coordination (perfect vs. non-perfect); purely aspective semantics of the continuous and the mixed tense-aspective semantics of the perfect. Oppositional presentation of the category. Oppositional reductions of the category. Aspective representation in verbids. | |

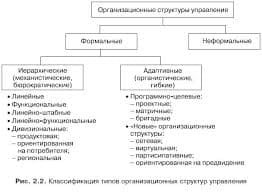

| Обобщенное значение категории вида – внутренне присущий способ реализации процесса. Вид тесно связан с временной семантикой, показывая, по словам А.М. Пешковского, «как действие распределяется во времени», или «темпоральную структуру» действия. Как и время, вид может выражаться лексически и грамматически. И это еще одна сфера грамматики, в которой английский язык значительно отличается от русского: в русском языке вид выражается только лексически, через разбиение на группы глаголов совершенного и несовершенного вида, делать – сделать; видеть – увидеть и т.д. Разбиение глаголов на глаголы совершенного вида и несовершенного вида является постоянным и очень жестким; это одна из основных характеристик грамматической системы русского глагола, она доминирует над системой времен и семантически, и формально. В английском языке (как было показано в Разделе 10), аспектное значение проявляется лексически в разбиении глаголов на предельные и непредельные, например: to go – to come, to sit – sit down и т.д. Однако, как уже отмечалось, большая часть английских глаголов легко мигрируют из одного подкласса в другой, и их аспектное значение передается, прежде всего, грамматическими средствами, т.е. через специальные формы глагольного словоизменения. Выражение аспектного значения в формах английских глаголов неразрывно связано с выражением временных значений; поэтому в практической грамматике они рассматриваются не как отдельные временные и видовые формы, а как особые видо-временные формы, ср.: продолженная форма настоящего – I am working; продолженная форма прошедшего – I was working; перфектная форма прошедшего и индефинитная форма прошедшего – I had done my work before he came, и т.д. Эта слитность временных и видовых значений и средств их выражения привела к тому, что категория вида и статус видо-временных форм глагола в английском языке вызывали и вызывают множество разногласий. Анализ категории вида в английском языке оказался одним из наиболее сложных разделов в англистике: четыре соотнесенных видовых формы, индефинитная (неопределенная), продолженная, перфектная и перфектно-продолженная, трактовались разными лингвистами в разное время то как формы категории времени, то как формы категории вида, то как формы со смешанной видо-временной семантикой, а то и вовсе не как формы категории времени, и не как формы категории вида, а как формы некой отдельной грамматической категории. | The general meaning of the category of aspect is the inherent mode of realization of the process. Aspect is closely connected with time semantics, showing, as A. M. Peshkovsky puts it, “the distribution of the action in time”, or the “temporal structure” of the action. Like time, aspect can be expressed both by lexical and grammatical means. This is one more grammatical domain in which English differs dramatically from Russian: in Russian, aspect is rendered by lexical means only, through the subdivision of verbs into perfective and imperfective, делать – сделать; видеть – увидеть; etc. In Russian the aspective classification of verbs is constant and very strict; it presents one of the most typical characteristics of the grammatical system of the verb and governs its tense system formally and semantically. In English, as shown in Unit 10, the aspective meaning is manifested in the lexical subdivision of verbs into limitive and unlimitive, e.g.: to go – to come, to sit – sit down, etc. But most verbs in English migrate easily from one subclass to the other and their aspective meaning is primarily rendered by grammatical means through special variable verbal forms. The expression of aspective semantics in English verbal forms is interconnected with the expression of temporal semantics; that is why in practical grammar they are treated not as separate tense and aspect forms but as specific tense-aspect forms, cf.: the present continuous – I am working; the past continuous – I was working; the past perfect and the past indefinite – I had done my work before he came, etc. This fusion of temporal and aspectual semantics and the blend in their formal expression have generated a lot of controversies in dealing with the category of aspect and the tense-aspect forms of the verb. The analysis of aspect has proven to be one of the most complex areas of English linguistics: the four correlated forms, the indefinite, the continuous, the perfect, and the perfect continuous, have been treated by different scholars as tense forms, as aspect forms, as forms of mixed tense-aspect status, and as neither tense nor aspect forms, but as forms of a separate grammatical category. | |

| Одним из наиболее сложных пунктов при рассмотрении категории вида является то же логическое противоречие, которое рассматривалось нами в связи с категорией времени: категория не может быть выражена дважды в одной и той же грамматической форме; члены парадигмы взаимно исключают друг друга; однако в английском языке существует двойная видовая форма – перфектно-продолженная. Это противоречие может быть разрешено так же, как и в случае с категорией времени: категория вида, как и категория времени, является не единой категорией в английском языке, а системой двух категорий. | One of the most controversial points in considering the category of aspect is exactly the same logical contradiction that we had to tackle when studying the category of time: the category cannot be expressed twice in one and the same grammatical form; the members of one paradigm should be mutually exclusive; but there is a double aspective verbal form known as the perfect continuous form. The contradiction can be solved in exactly the same way that was employed with the tense category: the category of aspect, just like the category of tense, is not a unique grammatical category in English, but a system of two categories. | |

| Первая категория реализуется через парадигматическое противопоставление продолженных, (длительных) и непродолженных (индефинитных, простых, неопределенных) форм глагола; эта категория может быть названа «категория развития». Маркированный член оппозиции, продолженная форма, образуется с помощью вспомогательного глагола to be и причастия первого знаменательного глагола, например: I am working. Грамматическое значение продолженных форм традиционно трактовалось как обозначение процесса, происходящего одновременно с неким другим процессом; эта временная интерпретация значения длительных форм была разработана в трудах Г. Суита, О. Есперсена и др. И.П. Иванова трактует значение продолженных форм как слияние временной и видовой семантики, как обозначение развивающегося процесса, происходящего одновременно с другим действием или временным центром. Большинство лингвистов сегодня поддерживают точку зрения, изложенную в работах А.И. Смирницкого, Б.А. Ильиша, Л.С. Бархударова и др., которые считают значение длительных форм чисто аспектуальным - «действие в развитии, развивающееся действие». Слабый, немаркированный член оппозиции, неопределенная форма, передает собственно факт совершения действия. Основной аргумент против того, что продолженные формы глагола выражают значение относительного времени, одновременность, заключается в следующем: одновременные действия могут быть выражены как продолженными формами глагола, так и непродолженными, ср.: While I worked, they were speaking with each other. – While I worked, they spoke with each other. Второе действие, одновременное с первым в обоих предложениях, в первом описывается как продолжающееся, развивающееся во времени, а во втором – приводится как факт. Одновременность, на самом деле, передается через синтаксическую конструкцию или через более широкий семантический контекст, поскольку для протекающего, развивающегося действия вполне естественна связь с неким временным центром. Кроме того, как уже упоминалось, аспектуальное значение продолженной формы может сочетаться со значением перфекта (в перфектно-длительной форме), а идея перфекта исключает возможность одновременности. | The first category is realized through the paradigmatic opposition of the continuous (progressive) forms and the non-continuous (indefinite, simple) forms of the verb; this category can be called the category of development. The marked member of the opposition, the continuous, is formed by means of the auxiliary verb to be and participle I of the notional verb, e.g.: I am working. The grammatical meaning of the continuous has been treated traditionally as denoting a process going on simultaneously with another process; this temporal interpretation of the continuous was developed by H. Sweet, O. Jespersen and others. I. P. Ivanova treated the continuous as rendering a blend of temporal and aspective semantics, as denoting an action in progress, simultaneous with another action or time point. The majority of linguists today support the point of view developed by A. I. Smirnitsky, B. A. Ilyish, L. S. Barkhudarov, and others, that the meaning of the continuous is purely aspective - “ action in progress, developing action ”. The weak, unfeatured member of the opposition, the indefinite, stresses the mere fact of the performance of the action The main argument against the idea that relative time meaning, simultaneity, is expressed by the continuous, is as follows: simultaneous actions can be shown with or without the help of continuous verbal forms, cf.: While I worked, they were speaking with each other. – While I worked, they spoke with each other. The second action, simultaneous with the first in both sentences, is described as durative, or developing in time in the first sentence and as a mere fact in the second sentence. The simutaneity is actually rendered by either the syntactic construction or the broader semantic context, since it is quite natural for the developing action to be connected with a certain time point. Besides, as we mentioned, the aspective meaning of the continuous can be used in combination with the perfect (the perfect continuous form), and the very idea of perfect excludes any possibility of simultaneity. | |

| Как любая грамматическая категория, категория развития может быть подвергнута контекстной редукции, и в большинстве случаев подобная редукция взаимосвязана с лексико-семантическими аспектуальными характеристиками глагола. Нейтрализация оппозиции категории развития регулярно происходит с непредельными глаголами, особенно статальными глаголами типа to be, to have, глаголами чувственного восприятия, отношения и т.п., например: I have a problem; I love you. Их неопределенные формы используются вместо продолженных по семантическим причинам: статальные глаголы сами по себе обозначают продолжающиеся, развивающиеся процессы. Поскольку эти случаи системно закреплены в английской грамматике (как глаголы, которые «никогда не употребляются в форме continuous»), использование статальных глаголов в продолженных формах можно рассматривать как обратную транспозицию (де-нейтрализацию оппозиции): их значение трансформируется, они становятся окказионально акциональными, и в большинстве случаев эти случаи стилистически маркированы, ср.: You are being naughty!; I’m loving it! Не используются продолженные формы и с чисто предельными глаголами, поскольку их значение не допускает выражения продолженности, за исключением тех контекстов, в которых специально требуется выражение действия в развитии, например: The train was arriving when we reached the station. Использование продолженных форм с предельными глаголами нейтрализует их лексическое аспектное значение, превращая их, наоборот, в окказионально непредельные глаголы. Нейтрализация оппозиции категории развития может происходить по чисто формальным причинам, чтобы избежать использования двух «инговых» форм рядом, например, если за глаголом следует причастная конструкция: He stood there staring at me. Классическим случаем стилистически окрашенной транспозиции в рамках категории развития является использование продолженных форм вместо неопределенных для обозначения регулярно повторяющегося действия в эмоциональной речи с явными негативными коннотациями, например: You are constantly grumbling! | As with any category, the category of development can be reduced and in most cases the contextual reduction is dependent on the lexico-semantic aspective characteristics of the verbs. The neutralization of the category regularly takes place with unlimitive verbs, especially statal verbs like to be, to have, verbs of sense perception, relation, etc., e.g.: I have a problem; I love you. Their indefinite forms are used instead of the continuous for semantic reasons: statal verbs denote developing processes by their own meaning, Since such cases are systemically fixed in English grammar (as the “never-used-in-the-continuous” verbs), the use of the statal verbs in the continuous can be treated as “ reverse transposition ” (“ de-neutralization” of the opposition): their meaning is transformed, they become actional for the nonce, and most of such cases are stylistically colored, cf.: You are being naughty!; I’m loving it! No continuous forms are used with purely limitive verbs whose own meaning excludes any possibility of development, except for contexts which specifically demand the expression of an action in progress, e.g.: The train was arriving when we reached the station. The use of the continuous with limitive verbs neutralizes the expression of their lexical aspect, turning them for the nonce, vice versa, into unlimitive verbs. The neutralization of the category of development can take place for a purely formal reason: to avoid the use of two ing -forms together; for example, no continuous forms are used if there is a participial construction to follow, e.g.: He stood there staring at me. The classic example of stylistically colored transposition within the category of development is the use of the continuous instead of the indefinite to denote habitual, repeated actions in emphatic speech with strong negative connotations, e.g.: You are constantly grumbling! | |

| Вторая видовая категория образована оппозицией перфектных и неперфектных глагольных форм; эту категорию можно назвать «категорией ретроспективной координации». Сильный член оппозиции, перфект, образуется с помощью вспомогательного глагола to have и причастия второго знаменательного глагола, например: I have done this work. Статус данной категории, как и статус первой аспектной категории развития, явился источником многочисленных разногласий в лингвистике. Все четыре выше упомянутых подхода прослеживаются в интерпретации данной категории. Традиционное рассмотрение перфекта как формы, выражающей значение времени («перфектное время»), а именно, предшествования одного действия относительно другого, было сформулировано в работах Г. Суита, Дж. Керма и других лингвистов. М. Дойчбейн, Г.Н. Воронцова и др. рассматривали перфект как чисто аспектную форму, подчеркивая тот факт, что перфектные формы обозначают некий результат, некоторый переход предшествующего события в последующее. И.П. Иванова рассматривает перфектные формы, как и продолженные формы, как средства слитного выражения временных и аспектуальных значений, противопоставленные индефинитной форме, у которой отсутствуют (нейтрализованы) аспектные характеристики. А.И. Смирницкий был первым, кто предложил рассматривать перфект как форму, образующую свою собственную категорию, которая не является ни временной, ни аспектной; он предложил называть эту категорию «категорией временной отнесенности». Главным аргументом, побудившим А.И. Смирницкого вынести трактовку перфекта за рамки вида, было то, что значение перфекта сочетается со значением длительности в перфектно-длительных формах, что невозможно, если рассматривать их как формы одной категории. Однако, если признать, как было предложено выше, существование не одной, а двух аспектных категорий, такое совмещение вполне возможно. Таким образом, суммируя все особенности перфектных форм, выявленные в рамках разных подходов, можно охарактеризовать грамматическую категорию, образуемую перфектными и неперфектными формами как особую глагольную категорию, семантически переходную в плане совмещения временных и аспектных значений. Формы перфекта означают предшествующее действие, последовательно связанное с последующим временным пределом или другим действием; последующая ситуация оказывается вовлеченной в сферу действия предшествующей ситуации. Гибридная семантика перфекта состоит из двух компонентов: предшествование (относительное время) и соотнесение, переход или результат (аспектуальное значение). Отсюда и обобщенное название категории - «категория ретроспективной координации». В разных контекстах могут акцентироваться либо одни, либо другие семантические компоненты перфекта, например, в предложении I haven’t seen you for ages акцент делается на предшествовании, а в предложении I haven’t seen you since we passed our last exam акцент делается на соотнесении двух событий. Когда перфект используется в сочетании с длительной формой, действие представляется как предшествующее, связанное с последующей ситуацией и развивающееся одновременно, например: I have been thinking about you since we passed our last exam. | The second aspective category is formed by theopposition of the perfect and the non-perfect forms of the verb; this category can be called “ the category of retrospective coordination ”. The strong member of the opposition, the perfect, is formed with the help of the auxiliary verb to have and participle II of the notional verb, e.g.: I have done this work. The status of this category, as well as the status of the category of development, has given rise to much dispute in grammar. All the four approaches mentioned above can be traced in the interpretation of this category. The traditional treatment of the perfect as the tense form denoting the priority of one action in relation to another (“the perfect tense”) was developed by H. Sweet, G. Curme, and other linguists. M. Deutchbein, G. N. Vorontsova and other linguists consider the perfect to be a purely aspective form, laying the main emphasis on the fact that the perfect forms denote some result, some transmission of the pre-event to the post-event. I. P. Ivanova treats the perfect, as well as the continuous, as the verbal form expressing temporal and aspective functions in a blend, contrasted with the indefinite form of neutralized aspective properties. A. I. Smirnitsky was the first to put forward the idea that the perfect forms its own category, which is neither a tense category, nor an aspect category; he suggested the name “ the category of time correlation ”. The main argument which led to the interpretation of the perfect outside the aspect system of the verb was the combination of the meaning of the perfect with the meaning of development in the perfect continuous forms, which is logically impossible within the same category. Still, if we admit that there are two aspective categories in English, this combination becomes possible. Thus, summarizing all the peculiarities of the perfect outlined within different approaches, we can characterize the opposition of the perfect and the non-perfect as a separate verbal category, semantically intermediate between aspective and temporal. The perfect forms denote a preceding action successively, or transmissively connected with a certain time limit or another action; the following situation is included in the sphere of influence of the preceding situation. So, the two semantic components constituting the hybrid semantics of the perfect are as follows: priority (relative time) and coordination, transmission, or result (aspective meaning). Hence the general name for the category is “ the category of retrospective coordination ”. In different contexts prominence may be given to either of these semantic components of the perfect; for example, in the sentence I haven’t seen you for ages prominence is given to priority, while in the sentence I haven’t seen you since we passed our last exam prominence is given to succession or coordination. When the perfect is used in combination with the continuous, the action is treated as prior, transmitted to the posterior situation and developing at the same time, e.g.: I have been thinking about you since we passed our last exam.

|

2015-03-20

2015-03-20 901

901